A bloody massacre. Illustration for True Stories of the American Indians by Edward S Ellis, nd.

Credit: Look and Learn

On Wednesday, July 1st, 1857, dawn had barely broken when a detachment of Company D, 10th Infantry soldiers from Fort Ridgely reached the Yellow Medicine River, five miles from the agency that bore the same name.

The party, including the soldiers commanded by Lieutenant Alexander Murray, was led by Charles Eugene Flandrau, the U.S. agent for the Dakota at Yellow Medicine Agency.

Flandrau had moved to Minnesota from New York in 1853 to practice law at Traverse des Sioux. He had passed the bar two years before, while in Minnesota, Flandrau served on the Territorial Council and the Minnesota territorial and state supreme courts.

Flandrau and his party, with several Indian guides, including a man named Beautiful Voice, had set out from the agency on receiving intelligence that three members of a band of Dakota Sioux led by Inkpaduta had arrived in the area.

A man the St. Paul Pioneer described as ‘a trusty Indian’ informed Flandrau that one of the three men was Roaring Cloud, a son of Inkpaduta.

Inkpaduta (Red End, Red Cap, or Scarlet Point), a war chief of the Wahpekute band of the Dakota (Santee Sioux), was born on the northeast side of Cannon Lake, present-day Minnesota, between 1800 and 1815. In his childhood, he survived a battle with smallpox, which killed several of his relatives and left him with a scarred face.

Inkpaduta’s father was Wamdisapa (Black Eagle), who removed his band of followers to the Vermillion River in South Dakota after they were exiled from the central band of Wahpekute led by Tasagi. Wamdisapa, Tasagi and their followers had been at war with the Sac and Foxes. According to Charles Flandrau, writing some years after the event, ‘it was the lawless and depradatory habits of the Indians under Wamdisapi that kept up the war.’

The Wahpekutes had fought the Sac and Foxes since at least 1766, in 1825, at Prairie du Chien; the United States government brokered a peace between the squabbling factions that defined the borders of the various tribes which called Minnesota home.

On 15 November 1827, two years after the treaty agreed upon at Prairie du Chien, Sac and Fox warriors attacked the camp of Tasagi’s near the Des Moines River. Wamdisapa’s wife was killed in the attack.

Wamdisapa was away from the village at the time. He later said, ‘I left my family, as I thought in safety…on my return to my lodge, everything was destroyed.’

After the attack on the village, Wamdisapa blamed Tasagi for signing the treaty and resumed his war with the Sac and Fox. Despite the fraught relationship that ensued, it wasn’t until the middle of the following decade that Wamdisapa and his followers separated from Tasagi’s band and decamped to the Blue Earth River, the river received its name from the blue-green clay that was formerly found along its banks. The river was called ‘Makato Osa Watapa’ by the Santee, ‘the river where blue earth is gathered.’

In 1842, the conflict between the Wahpekute and the Sac and Fox tribes ended when the latter left their lands in Iowa, and the Sac and Fox moved further west.

A member of his band killed Tasagi in about 1839; the popular belief was that Wamdisapa and Inkpaduta were involved in the assassination.

A missionary to the Dakota at Traverse Des Sioux, Stephen Return Riggs, stated that Wamdisapa had offered sympathy when his brother-in-law drowned. Riggs added that Wamdisapa usually begged on his visits and had not created a pleasant impression.

Riggs reported that Wamdisapa had fallen ill in the summer of 1846 and believed the chief had died shortly afterwards. After his death, the Wahpekutes fragmented further, and a man named Sintominaduta (Red All Over, or Two Fingers) became chief; Inkpaduta assumed the role of sub-chief. Some sources suggest that the two men were brothers.

Two years later, in 1848, settlers along the Boone River, Iowa, reported that they had been raided often by warriors led by Sintominaduta. The actions of this band of Wahpekutes encouraged the authorities to build Fort Dodge.

In 1851, a group of eighteen Wahpekutes, including Wahmundeeyahcahpee (War Eagle That May Be Seen), a son of Tasagi, were killed in a fight with a band of Sac and Fox warriors. Initially, the blame for the slaughter had been laid at the feet of Inkpaduta; it was only later that the real culprits were revealed. Minnesota Territorial Governor Alexander Ramsey called for the perpetrators to be apprehended, but no action was taken.

Later the same year, when Governor Ramsey and Luke Lea, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, concluded the Treaty of Mendota with the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute, neither Inkpaduta nor Sintominaduta were involved in the negotiations.

The Treaty of Mendota was signed near Pilot Knob in the vicinity of Fort Snelling. The agreement compelled the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute bands to move to the Lower Sioux Agency on the Minnesota River; they would receive $1,410,000 from the government. Moving the two bands to the agency opened much of southern Minnesota up for white settlement.

Henry Lott arrived in Iowa around 1846. In the winter of 1846-47, he lived at the mouth of the Boone River in present-day Webster County. Lott, described as ’ a mean man’ by a neighbour’s son, traded ‘whiskey and trinkets’ with the local natives.

In December 1846, a group of men called ‘Lott’s Marauders’ stole a herd of ponies from Sintominaduta’s village. The Wahpekutes trailed the herd to Henry Lott’s property, where they discovered the animals secreted in a wood and recovered them.

Sintominaduta ordered his men to burn Lott’s cabin and kill his cattle. Henry Lott made his escape, fleeing in the company of a stepson in one telling of the story or alone in another version. Lott hid in the brush, watching as Sintominudata’s followers set his cabin ablaze and fired arrows into his cattle.

Having decided that discretion was the better part of valour, Lott removed himself to John Pea’s property at Pea’s Point. Lott described hearing screams from his wife and children as the Wahpekute men slaughtered them.

John Pea immediately proposed gathering a force and returning to the Boone River. Henry Lott was dispatched to Elk Rapids, sixteen miles away, where he encountered a camp of Potawatomis led by a chief named Chimisne; the settlers had given him the anglicised name of Johnny Greene.

Chimisne, along with twenty-six of his warriors, agreed to return to Pea’s Point with Lott. Pea’s men mistook the Potawatomi warriors for Sintominudata’s raiders. They prepared to open fire on them, but it was only when they saw Henry Lott riding alongside them that they put their weapons down.

John Pea, his brother Jacob, and some other men joined Lott and his new-found allies and returned to the Boone River. Contrary to what Lott had reported, his family had not been tomahawked, and his cabin still stood.

Mrs. Lott informed Dr. Spears, who had returned to the scene of the supposed massacre as part of Henry Lott’s auxiliary force, that Sintominudata had instructed her twelve-years-old son Milton to retrieve the horse herd or the Wahpekute warriors would kill them.

Instead of retrieving the horses, Milton, without donning either a hat or thick coat, set off in pursuit of Lott, who, according to different sources, was either his father or stepfather.

Sintominudata’s raiders drove three horses away from Lott’s property, and one of the animals fell through the ice as they crossed the river. The Wahpekutes shot the horse and rode on, happy with the booty they had looted from the property, which included a set of silver cutlery Mrs. Lott had been presented with by her first husband.

Jacob Pea remained at the Lott cabin while the remainder of the men returned to Elk Rapids. Henry Lott and Jacob Pea set off in pursuit of the missing Milton. On 18 December, the two men found Milton’s frozen corpse lying beside the ice-covered Boone River.

The ground was too hard for shovels to penetrate, so Lott and Pea placed the boy’s body in a hollow log. The following month, Lott, in the company of settlers from Pea Point, returned to the spot and interred Milton’s body in the ground. In November 1905, the Madrid Historical Society placed a tablet marking Milton Lott’s resting place.

Mrs. Lott died not long after the raid on her cabin; she was buried on a high bluff overlooking the cabin. Henry Lott gathered what remained of his livestock and his children and moved to Des Moines township and Fort Des Moines, where he married again.

Henry Lott returned to the site of the old cabin by the Boone River sometime after 1849. His wife bore him three more children: two daughters and a son. Soon after the son was born, the second Mrs. Lott died.

Not wishing to be burdened or perhaps not feeling able to care for the children, Henry Lott left his son with T.S. White. White lived a short distance from Fort Dodge and eventually adopted the boy. The two girls were left in the care of Dr. Hull and were raised by the Dickerson family.

In January 1854, Lott and a son from his first marriage discovered that Sintominudata and his family were camped along a creek that would become known as Bloody Run.

Lott and his son approached the Wahpekute camp. Lott was making a living as a trader of whisky and goods, so it wouldn’t be a giant leap to suggest that he carried a few bottles of firewater. It had been eight years since Sintominudata and his followers had raided Lott’s cabin, killed some of his livestock, and ransacked his house. Lott had returned to the same area, and presumably, Sintominudata knew who his visitor was.

Lott ‘made a profession of warm friendship for the Indians.’ Perhaps he uncorked a bottle and passed the whisky to Sintominudata at this point. He confided to the chief that on the river bottoms roamed a large herd of either elk or buffalo and suggested that the Wahpekute should go and hunt them.

After Sintominudata had ridden off to hunt the game, Lott and his son hid themselves in the undergrowth and waited for the return of the Wahpekute.

As the chief came into sight, the Lotts fired from their place of concealment and shot him from the back of his mount.

Waiting until night had fallen, the trader and his son approached the camp, where the rest of Sintominudata’s followers waited for the chief’s return. ’They gave the war-whoop,’ and as the women and children emerged from their tents, the two white men proceeded to shoot them down. Two children possibly survived the slaughter that followed.

Sintominudata’s mother, wife and two children were killed, as well as two other children. Lott and son ‘plundered the camp of every article of value, burned their cabin, loaded a wagon with plunder….crossed the Missouri north of Council Bluffs, and disappeared on the plains.’

Inkpaduta reported the murders to Major Williams at Fort Dodge. An inquest was held, and members of the jury disagreed with Inkpaduta’s assertion that Henry Lott was the killer. Instead, they placed the blame on other Indians who disliked Sintominudata.

Major Williams, who believed that Henry Lott was the killer, investigated further. Evidence was presented to the grand jury at Des Moines, and an indictment for murder was returned against Lott. Sheriff D.B. Spalding went out looking for Lott the day after the indictment was issued but returned without the wanted man. A few months later, Lott’s stepson informed the authorities that his father had been killed in California.

The winter of 1856-1857 was severe, with heavy snowfalls. Inkpaduta’s band of Wahpekutes was camped near the settlement of Smithland, close to the Little Sioux River.

The white settlers of Smithland were wary of the Wahpekutes being in their immediate vicinity. The Wahpekutes were starving and were equally distrustful of the whites. The tension between the two parties was palpable, and soon, the incident that sparked the series of killings that came to be known as the Spirit Lake Massacre would occur.

Inkpaduta’s band were hunting near Smithland when they encountered a party of settlers, described as a ‘vigilante group’ by at least one source. During the confrontation between the two parties, a dog belonging to one of the settlers was believed to be killed. A gun was taken from the man who shot the dog, and it was also reported that he was beaten.

Other reports suggest that the Wahpekutes were relieved of all their firearms and were informed that the vigilantes would return the next morning. When dawn broke the following day, the Indians had moved on towards the lakes.

In February, a warrior approached the Gillett cabin at Lost Island Lake, in the north of Iowa, intending to steal food, weapons and livestock. The Wahpekute man was shot and then decapitated by the homesteader.

Moving on, Inkpaduta’s men, fuelled with more rage after the killing and beheading of their comrade, attacked the home of Ambrose S. Mead on the Little Sioux River in Clay County. Mead had his cattle killed, his wife knocked down, and his 10-year-old daughter Emma beaten with a stick by Inkpaduta when she resisted attempts to snatch her. Emma’s older sister Hattie was not so fortunate; she was kidnapped along with a Mrs Taylor; both were released the following day. Inkpaduta assaulted Mrs Taylor’s husband and threw her son into the fireplace, burning the boy’s leg.

Rowland (or Roland) Gardner led a group of settlers to the area around Spirit Lake in 1856. Gardner built a cabin on the south side of West Okoboji Lake. Rowland and his wife Frances shared the home with their three youngest children: 16-year-old Eliza Matilda, 13-year-old Abigail, and six-year-old Rowland Jr.

The Gardners’ eldest daughter, Mary, lived nearby with her husband, Harvey Luce, and their two young children. Six other families, including the Nobles, Thatchers, Marbles, and a handful of single men, lived in the Spirit Lake area.

On Sunday, 8 March, the Gardners were at breakfast when Roaring Cloud, son of Inkpaduta, burst into their cabin and demanded that he be fed. Frances fed the man breakfast, and he demanded more food once he finished. A comrade of Roaring Cloud had removed the firing mechanism from Rowland’s gun while the chief’s son consumed his repast.

Roaring Cloud then levelled his gun at Harvey Luce’s chest; Harvey managed to grab the barrel of the weapon, preventing Roaring Cloud from discharging the firearm. After a tense standoff, the Wahpekute men stalked from the cabin. A short time later, two of the Gardners’ neighbours, Dr. Isaac Harriott and Bertell Snyder, both single men, arrived at the cabin. They had learned that Rowland was planning to ride to Fort Dodge to obtain supplies. Harriott and Snyder had letters they wished Gardner to mail for them, but after the morning events, Rowland was unwilling to ride off to Fort Dodge, leaving his family alone. Snyder and Harriott left with their letters.

Around Noon, the Wahpekute warriors killed some cattle belonging to the Gardner family. They then left and headed towards the two Okoboji lakes, where other settlers had built cabins.

James Mattock, his wife and five children had made their home on the land between West and East Okoboji lakes. 18-year-old Robert Maddison and his father shared the Mattocks’ cabin. Bertell Snyder and Dr. Harriott lived in a neighbouring building with two brothers, William and Carl Granger.

The Indians fell on the cabins between the lakes, killing everyone they found. Carl Granger was shot outside his cabin; the Wahpekute warriors chopped the top of his head off with an axe. The only resident of the cabins who escaped the massacre was William Granger, who was visiting relatives in Minnesota Territory.

After killing the Mattocks and their neighbours, the Wahpekute party returned to the Gardner cabin, where Harvey Luce and another man had left to warn settlers living nearby of possible trouble.

Rowland Gardner was outside when he saw nine of the Wahpekute raiders returning. Reportedly, he called into the cabin: ‘We are all doomed to die!’ And vowed to sell the lives of his family dearly.

Unaware of the fate of the Mattocks and their neighbours, Frances urged her husband not to fire. Heeding his wife, Rowland set his weapon aside and allowed the raiders into his cabin.

One of the Wahpekute demanded flour. When Rowland opened the barrel, one of the Indians shot him in the heart. Some of the raiders then grabbed hold of Frances Gardner and Mary Luce, her eldest daughter, and pinioned their arms, other men wielding rifles as clubs stove their heads in.

As the slaughter of her family was taking place in front of her, Abigail sat frozen by shock in a chair; her sister Mary’s young child was torn from Abigail’s grasp and, along with Rowland jr, taken outside, where they beat them with firewood and left them for dead. Witnessing the killing of her family, Abigail begged the Wahpekute to kill her, too; the Indians told her that she would not be killed. Instead, she would be taken prisoner.

Abigail Gardner spent her first night of captivity near the ruins of the Mattock Cabin. Her brother-in-law Harvey Luce was shot on the shore of East Okoboji Lake with the other man who had accompanied him as he warned their neighbours about the possibility of Indian trouble.

Joel Howe was intercepted out on the trail; he was killed and decapitated, and his head was recovered from a beach on East Okoboji two years later. The Wahpekute then attacked Howe’s cabin, killing his memorably named wife Rheumilla, five sons aged between nine and twenty-five, an 18-year-old daughter, and two visitors to the home.

Lydia Howe Noble, the 21-year-old daughter of Joel and Rheumilla, lived with her husband Alvin nearby. The Noble home was the next cabin to be visited by Inkpaduta’s men.

The raiders stormed into the Noble cabin and shot Alvin Noble and Enoch Ryan, who was visiting at the time. They snatched a two-year-old child from Lydia and a baby from the arms of Elizabeth Thatcher, took the infants outside, and ‘bashed their brains out on an oak tree.’

Taking Lydia and Elizabeth prisoner, they returned to the Howe cabin, where 4-year-old Jacob was still alive and sitting outside the cabin; he was quickly dispatched by one of the Indians. Lydia found the body of her mother under the bed, her head crushed in by a flat iron.

It was the following day when news of the killings reached the town of Springfield, Minnesota Territory. Morris Markham had spent the winter at the Noble-Thatcher residence; he had spent the previous two days rounding up stray livestock; he passed the Gardner place and discovered the scene of slaughter. He quickly made more grisly discoveries when he returned to the Noble-Thatcher cabin, where more murdered and eviscerated bodies greeted him.

Markham headed to Springfield, which lay about 18 miles to the north of Spirit Lake. At that settlement, he found Eliza Gardner, who had been paying a visit to Dr. And Mrs. Strong. Markham informed Eliza that her family, apart from Abigail, whose body he couldn’t find, had been slaughtered by Inkpaduta’s force.

The day after Morris Markham had reached Springfield, Inkpaduta and his band moved further west. On 13 March, they arrived at the home of William and Margaret Ann Marble. The Marbles were unaware of the trouble that had broken out around Spirit Lake.

The Marbles invited the Wahpekutes into their cabin and fed them. Afterwards, one of the Indians traded for William’s rifle and challenged him to a target shoot. After the parties had fired at the target, it fell over; as William bent over to pick the target up, he was shot in the back. Marble’s corpse was stripped of a money belt that contained $1,000.

Margaret Ann watched the shooting contest take place from the cabin door. When she saw her husband shot down, she tried to flee, but she was quickly caught by the warriors and taken captive. Inkpaduta’s men had now captured three women and the teenage Abigail Gardner.

A fortnight after William Marble was killed, the Wahpekute band was camped at Heron Lake, about 15 miles from Springfield. The warriors were dressed for war; they told the four captives that they were planning to attack the settlement of Springfield. Abigail was horrified that Eliza ‘would either be killed, or share with me what I felt to be a worse fate—that of a captive.’

Although Morris Markham had forewarned the settlement of Springfield about the presence of hostile Indians, the Wahpekute band stole a parcel of horses as well as other goods. They killed seven citizens of the town, including three children.

Two days after the skirmish at Springfield, a detachment of 24 soldiers from Fort Ridgely under Lieutenant Alexander Murray came within sight of where the Wahpekute and their prisoners were encamped. The soldiers retreated after failing to find their quarry.

A few weeks later, a teenage warrior pushed Elizabeth Thatcher into the water while crossing the Big Sioux River on a fallen tree. Elizabeth swam to the other bank, where other warriors began striking at her with clubs and poles; she swam to the other bank and received the same treatment. Thatcher was forced downriver. Eventually growing tired of their sport, they shot her and let her body drift downriver with the current.

Lydia Noble was left devastated by the death of her cousin and, with little hope of rescue, suggested that she and Abigail should drown themselves. Abigail refused, and Lydia did not have the strength to act alone.

On 6 May, two Sioux brothers from the Yellow Medicine Reservation visited Inkapaduta’s encampment on Skunk Lake. They spent the night listening to the Wahpekute warriors’ exploits at Spirit Lake and beyond. In the morning, they offered to trade for Abigail Gardner; Inkpaduta was unwilling to trade Abigail. Instead, the brothers left the camp with Margaret Ann Marble. Margaret was taken to the Yellow Medicine Reservation, and later, she was accompanied to St.Paul by Charles Flandrau.

A month after the two Sioux brothers redeemed Margaret Marble, Inkpaduta and his followers met up with a group of Yankton Sioux. One of the Yankton men, End of the Snake, wished to get a reward from the white authorities by returning the remaining captives.

Inkpaduta agreed to sell Abigail and Lydia to the Yankton. A few nights later, Roaring Cloud stormed into the tepee of Roaring Cloud, where Lydia Noble was staying, and demanded that she go with him. Lydia refused to leave the tent with Inkpaduta’s son; he dragged her from the tent and, using a piece of firewood which Lydia had just cut, beat her around the head with it mercilessly. Roaring Cloud only stopped striking the captive to wash the blood from his hands.

Lydia lay moaning outside the tent for half an hour before she died. Abigail reported that the following day, Lydia was scalped, and her corpse was used as target practice. After they left the camp, one of the Wahpekute men repeatedly slapped Abigail in the face with Lydia Noble’s bloody scalp.

Towards the end of May 1857, Abigail Gardner’s immediate nightmare ended. Supplied with goods by Charles E. Flandrau, three Sioux men, Beautiful Voice (Hotonhowashta), who would help track down Roaring Cloud, Iron Hawk (Chetanmaza) and the man with quite possibly the best name in the history of the American West, Man Who Shoots Metal as He Walks, or John Other Day (Mazakutemani), reached Inkpaduta’s camp. It would be interesting to learn the etymology of Mazakutemani; he is an interesting man who fought on the side of the whites in the 1862 Minnesota Sioux uprising.

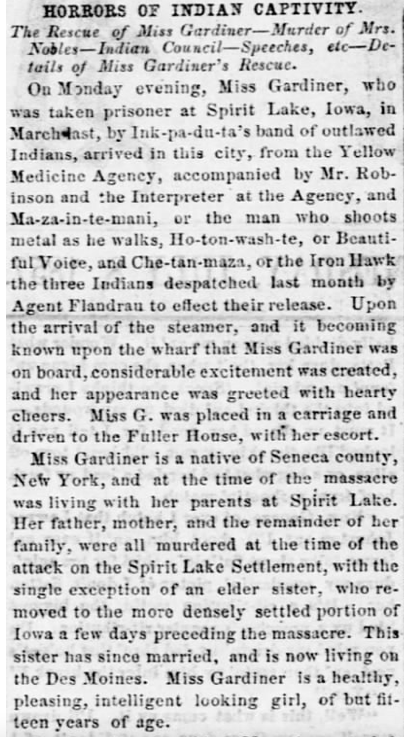

Flandrau’s emissaries negotiated with Inkpaduta for three days before securing Abigail Gardner’s freedom. In exchange for the girl, Inkpaduta’s band received two horses, 12 blankets, two powder kegs, 20 pounds of tobacco, 32 yards of blue cloth and 37 yards of calico. According to the Raftsman’s Journal, Beautiful Voice and his companions received $1200 for their services.

Raftsman’s Journal, Wednesday, 8 July 1857

Abigail Gardner was reunited with her sister Eliza on 5 July in Hampton. On 16 August, despite being only 13, Abigail married Casville Sharp, a cousin of Elizabeth Thatcher. The pair went on to have three children, two boys and a girl, who died in infancy.

When the party, guided by Beautiful Voice, reached the village on the Yellow Medicine River, they immediately surrounded the lodge where Roaring Cloud was staying.

After seeing Flandrau and one of the guides, Roaring Broke fled from the lodge to a ravine, where he hid in the grass. Lieutenant Murray’s command surrounded the ravine ‘and with difficulty discovered the Indian, upon whom they immediately fired, inflicting several severe wounds.’

The Tipton Advertiser reported that Roaring Cloud, returning fire with a double-barrelled shotgun, ’struck the cartrige box of a soldier, who there upon rushed forward and bayonetted the savage.’

Flandrau’s force left Roaring Cloud’s body on the ground; securing his wife, they left the village and returned to the Yellow Medicine Agency. Roaring Cloud’s wife was soon released, mollifying the Indians somewhat.

The settlers of Iowa were concerned that Inkpaduta, on learning of the death of his son, would enact revenge on the white community. The military force at Fort Ridgely was small ‘, and this seemed to encourage the Indians in assuming a bold and haughty tone.’

Inkpaduta, the man Abigail Gardner described ‘as a savage monster in human shape, fitted only for the darkest corner of hades,’ apparently took no action after Roaring Cloud’s death. He played a minimal part in the hostilities in 1862. After the Battle of The Little Bighorn, Inkpaduta crossed the Medicine Line into the nascent country of Canada, dying in Manitoba in 1877.

Sources

Newspapers

The Tipton Advertiser

St. Paul Pioneer

Raftsman’s Journal

Websites

https://sites.rootsweb.com/~iaboone/history/lott-story.htm

http://iagenweb.org/polk/bios-fam-stories/POPCI_Vol_2/H_Lott/H_Lott.html

https://www.britannica.com/event/Spirit-Lake-Massacre

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spirit_Lake,_Iowa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Eugene_Flandrau

https://www.historynet.com/spirit-lake-massacre/?f

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inkpaduta

© Mark Young 2024

Leave a reply to sudha verma Cancel reply