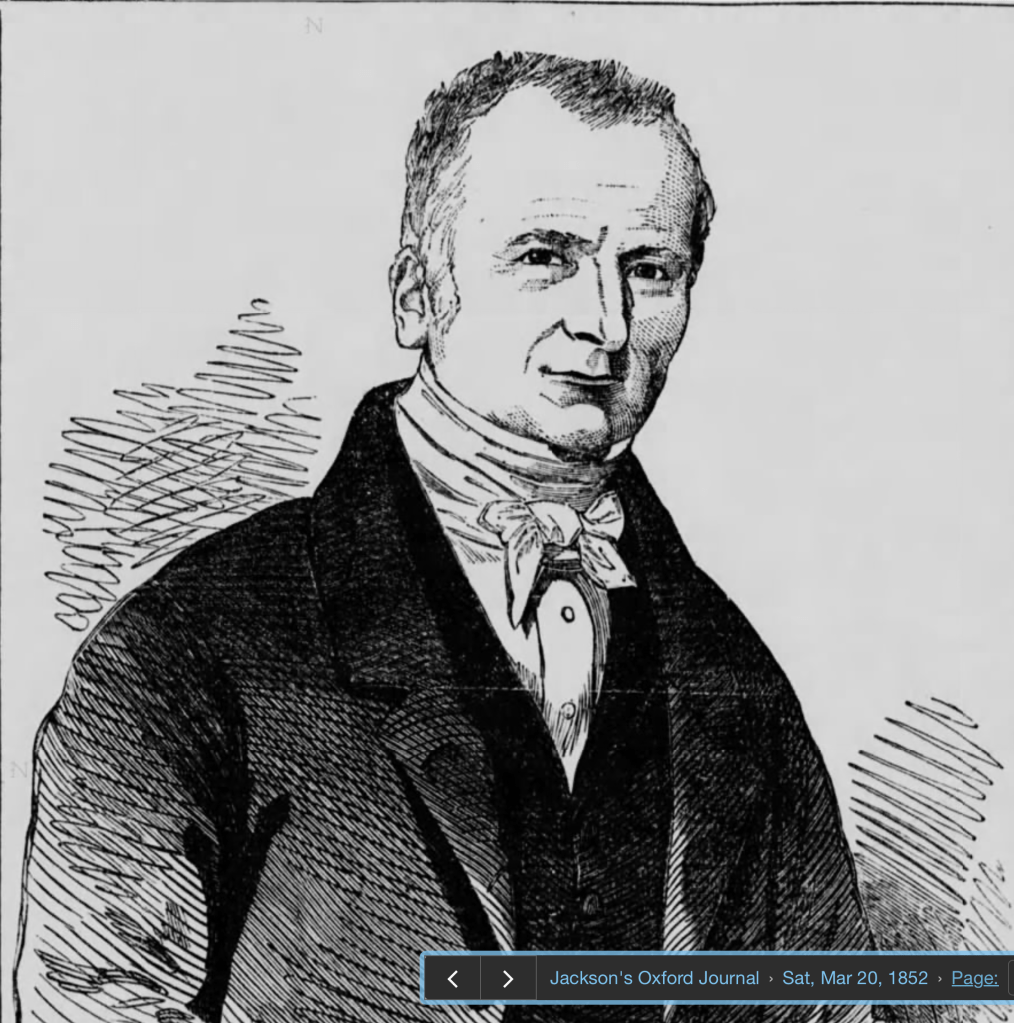

Portrait of John Kalabergo. Engraved by E. Jewitt of Camden Town. The original was in the possession of Mr. Craddock, of Banbury, Oxfordshire.

On Saturday, 10 January 1852, Dr. Harris’, a surgeon at the Queen’s Hospital, Birmingham, visit to his father’s house in the north Oxfordshire hamlet of Williamscote (now Williamscot), was disturbed by the arrival of a messenger informing him that a man had fallen from his cart onto the road and had been conveyed to the Rose and Crown pub by local farmer Richard Andrews. The messenger added, as an afterthought, that two hats had been found next to where the accident had occurred.

James Ward, a farm labourer, had alerted Richard Andrews to the presence of a body in the road. ‘Master, there’s a man found dead on the hill,’ he said.

Andrews told an inquest held the following week that he had said: ‘He won’t lie there; it’s in our parish and in Oxfordshire.’ The farmer took a cart, lined the bottom with straw and headed to where the body lay.

When he reached the body, Andrews procured lanterns from some bystanders and identified the man, an Italian, by his anglicised name, John Kalabergo. Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Kalabergo, a native of Chiavenna, Austrian Lombardy, had fled his homeland to avoid ‘the tyrannical conscriptions of the Emperor Napoleon.’

By trade, a jeweller and silversmith, Kalabergo went into business in Banbury. Over time, thanks to his hard work and popularity with the locals, his business grew. In the late 1840s, he was away in Italy for about 20 months before returning to Banbury.

In late 1851, Giovanni was joined in England by his nephew Guglielmo. Guglielmo was in the habit of joining his uncle in his light spring wagon, filled with Giovanni’s goods, as they travelled around Banbury and the surrounding areas.

On 9 January, the Kalabergos left Banbury at around 10 a.m. They travelled around thirteen miles, reaching the village of Priors Marston that evening. They spent a leisurely morning in the village before leaving to return to Banbury in the middle of the afternoon.

By late afternoon, the pair were seen in Chipping Warden, where they paused for a few minutes at the Rose and Crown public house, before continuing towards Banbury. They passed through the Williamscote upper turnpike-gate, where Giovanni paid Anna Ward, the gatewoman the toll and received a ticket from her to clear the Banbury gate.

On the Banbury road, the Kalabergos were passed by a covered cart driven by a Mr. Walker, a publican and baker, who recalled seeing the pair at the Rose and Crown in Chipping Warden. When Walker’s conveyance passed the Kalabergos, Giovanni was walking slowly up a hill, as his nephew stood beside the horse.

Shortly after passing the two Italians, Mr. Walker and his companion heard the report of a pistol, followed almost immediately afterwards by a second shot. Unconcerned by the gunfire,

which was presumably a rare occurrence in rural north Oxfordshire, Walker and his friend continued on their way to Banbury.

That same evening, a coach ferrying passengers from Banbury encountered a cart seemingly abandoned outside of Williamscote. The passengers had disembarked the coach as it made its way up a hill when one of the passengers, in advance of the others, discovered a body in the road. As noted above, Richard Andrews identified the body as ‘John’ Kalabergo.

Robbery did not appear to be the motive for the murder. Giovanni Kalabergo’s pockets hadn’t been rifled, and the boxes in the cart, which contained jewellery, had not been opened. But where was Guglielmo Kalabergo? On the road next to the cart lay two hats, one presumably belonging to Giovanni, but who owned the second?

James French, a labourer, encountered an emotional Guglielmo Kalabergo by a row of houses known as the Huscot Cottages on the Banbury road. Guglielmo had lost his hat, and was crying and ‘seemed in great distress. He called out, “Master! Master!” And pointed in the direction of Williamscott’.

Guglielmo was next spotted in Banbury at the house of Dr. Tandy, a Roman Catholic Priest in the town. He knocked on the door several times, calling out, ‘Priest, priest! Uncle dead!’ In his fractured English.

He then went to his uncle’s house, where Sophia Roberts, Giovanni’s housekeeper, met him. There were also present two sisters, Louisa and Harriet Egg, who ran a millinery business and lodged with Giovanni. Appearing highly agitated, Guglielmo again stated that his uncle was dead and asked for the priest.

Sophia Roberts then rushed to Dr. Tandy’s house and brought the Italian-speaking priest back to Giovanni’s house. Dr Tandy found it challenging to understand Guglielmo’s dialect, but gathered that three men had jumped out at Giovanni and beaten him with sticks. It was then that the priest decided to involve the police.

Tandy and Guglielmo set out for the house of the Banbury’s police superintendent. On their way, they met Giovanni’s cart. Guglielmo asked if his uncle was dead. ‘Upon being answered in the affirmative, he broke out into fresh paroxysms of grief, and sobbed and cried bitterly.’

That evening, Guglielmo was visited by ‘Mr. Samuelson, an ironfounder…who also spoke Italian.’ The bereft nephew explained that a man had jumped out of a hedge as the Kalabergos cart rumbled out of Williamscote. The man asked ‘them for their life or their purse.’ In response, Giovanni raised a stick he had been carrying and aimed a blow at the man. A second man then appeared and fired a shot at Giovanni. At this point, Guglielmo took to his heels and was pursued across a field by a third man. ’The man shouted “stop, stop,” and followed him for eight or 10 minutes.’ Guglielmo also stated that he had encountered a man with a horse and cart, and tried to alert him, but the man couldn’t understand him.

Apparently, the Banbury police were unconvinced by Guglielmo’s story, and he was taken into custody that night. News of the murder of Giovanni Kalabergo soon spread around the local area, and several people came to visit the prisoner on the weekend of his arrest.

One of the curious locals was a man named Thomas Watkins, who worked in his uncle’s Mr. Welch’s gun shop in the town. He identified Guglielmo as the man who purchased a double-barrelled pistol on 15 December. Watkins asserted that he had instructed Guglielmoon how to load and fire the weapon. Guglielmo paid £1 for the pistol, and also received a woollen bag to keep the gun in, as well as a bullet mould. Watkins then demonstrated for his customer how to make a bullet. Before leaving Welch’s shop, Guglielmo purchased a quarter pound of gunpowder, which Watkins wrapped up in a copy of the Banbury Pilot, a local newspaper.

On 26 December, Guglielmo Kalabergo visited a second Banbury gunmaker, William Holland, where he tried unsuccessfully to exchange the pistol he had purchased at Welch’s for another weapon. After his arrest, Guglielmo was searched, and a small quantity of gunpowder was found in his waistcoat pocket, as well as a copper cap and the turnpike ticket, which Giovanni had received when passing through the Williamscote turnpike.

The evening he had been taken into custody, the police asked Guglielmo for the key to Giovanni’s cart. ‘Me no key, uncle got the key,’ he insisted. After denying any knowledge of the key, Guglielmo went into the garden attached to the house to visit the privy.

The next morning, Monday, 11 January, a thorough search of Giovanni’s house was undertaken. The key to the cart was found in the privy. Within the stable, a bullet mould identified by Watkins as the one he had sold to Guglielmo was discovered.

In the rafters of the stable, six bullets made of white metal were found. The bullets were similar to the one that had been extracted from Giovanni Kalabergo’s skull during the inquest that was carried out the week following the murder.

After his arrest, Guglielmo was transported from Banbury to nearby Wroxton, where he was held in a locked room with two constables. Despite the presence of the police officers, the prisoner made a desperate attempt to escape and leapt through an open window. Breaking his leg in the fall, Kalabergo was recaptured a short distance away.

On 23 February, authorities began a search around the area in which Giovanni Kalabergo’s murder took place, hoping to find the missing murder weapon. In the days after the killing, the inclement weather had prevented a thorough search from taking place. The water level in the ditches had subsided.

Constable Newton was searching a ditch beside the road, which it was supposed that Guglielmo had fled along after his uncle was killed, and found a great coat which was positively identified as one of three which Giovanni had in his cart around the time he was killed. A short distance from the coach, a pistol with the name ‘Welch’ engraved on the handle was discovered. Thomas Watkins would soon confirm that the pistol was the same weapon he had sold on 15 December to Guglielmo.

The trial of Guglielmo Giovanni Bazelli Kalabergo took place during the Oxfordshire Lent Assizes at County Hall, Oxford, on Wednesday, 3 March 1852. Mr. Pigott and Mr. Huddlestone represented the defendant’s interests. Mr. Keating, Queen’s Counsel (QC), and Mr. Cripps prosecuted the case. Mr. Maggione was sworn in and acted as interpreter during the proceedings. The Judge was Mr. Justice Wightman, who had arrived from Reading on the Great Western Railway the previous Saturday.

Wightman had remarked at the beginning of the assizes on the number of cases set before him, ‘not only in the number, but in the character of the offences with which the prisoners were charged. There was one charge of wilful murder, four of maliciously wounding, three of burglary…three of highway robbery, two of arson, and others of a serious nature.’

The prosecutors laid out their case thoroughly. Detailing the discovery of the key in the privy, the bullets and mould, along with the gunpowder found in the stables. Witnesses described Guglielmo’s strange behaviour and his attempted flight from justice. The search of the ditches, which had brought to light the pistol which Thomas Watkins testified he had sold to the defendant. At 7 p.m. The court adjourned.

Early the next day, eager crowds thronged the streets around City Hall, keen to bear witness to the denouement of the trial. Mr. Pigott, for the defence, rose and addressed the court for upwards of three hours.

When the defence rested, Mr. Justice Wightman summed up the case for the jury. Pointing out that all the evidence brought forward by both legal teams was circumstantial. ‘There was no direct evidence that the prisoner at the bar had committed this atrocious crime; but they would have to consider whether the facts which had been proved before them excluded the reasonable probability of the offence having been committed by any other person.’

The judge then went through the evidence in great detail, finishing his summing up just after 1 p.m. Dismissed to consider their verdict, the jury were out for just 15 minutes, returning with a verdict of guilty.

Justice Wightman donned the black cap, ‘and in a brief and solemn address, pronounced upon the prisoner the sentence of death.’

Maggione, the court-appointed interpreter, translated for the prisoner, ‘but he appeared to display little emotion.’ Press reports suggested that Maggione was more upset by the verdict than Kalabergo was.

The day after the sentence of death was imposed on Guglielmo Kalabergo, he was exercising in the yard at Oxford Castle, where he was incarcerated prior to his scheduled execution, the prison officer guarding him was temporarily distracted, seizing his moment, Guglielmo ‘made a desperate leap, and succeeded in scaling the wall like a cat.’

The prisoner ran along the wall, jumped upon another one, as the desperate prisoner officers sounded the alarm. Thinking he had reached the boundary of the prison, Guglielmo’s hope of escape was thwarted when he realised that he had reached a dead-end. Guglielmo sat down atop the wall and waited for the guards to fetch a ladder. Once restored to his cell, the prisoner was manacled securely.

The following Monday, Kalabergo confessed to Dr. Tandy, the Roman Catholic priest from Banbury, also present was the Rev. Dr. Harrington, principal of Brasenose College. ‘I, William (Guglielmo) Kalabergo, declare that I am guilty of this crime of murder done upon my uncle, John (Giovanni) Kalabergo.’

Guglielmo Kalabergo was hanged at Oxford Castle on Monday, 22 March 1852, at eight a.m. A crowd numbering about 10,000 assembled, composing ‘mostly of the middle and working classes, but chiefly the latter, and included a considerable number of women.’

On the scaffold, the condemned man made ‘solemn calls for mercy, stood erect and alone while the noose was fastened, the cap drawn over his eyes, the chain taken from his feet, and the platform removed from under him. On falling, he appeared to be almost instantly dead, but convulsions ensued. Life was soon extinct.’

In the confession he had made to Dr. Tandy, Guglielmo stated that he had wished to join his uncle in England for some time. Giovanni had always denied the request before finally assenting, but insisting that Guglielmo should be ‘attentive to his religious duties, and avoid bad company.’ Once in Banbury, Guglielmo struggled with the constraints imposed on him by his uncle. Giovanni often appeared angry and scolded Guglielmo, especially at meals, threatening to turn him out onto the streets.

‘This exasperated the nephew; and at length the devil put it into his head that if he were to kill the old man, he should at once get rid of the torment, and obtain possession of his property as his heir.’ Guglielmo purchased the pistol from Welch’s with the intention of killing his uncle.

He confessed that he had carried out other thefts. 15 shillings were found in his pockets when the police searched him the night of the murder. He stole two gold watches, three silver watches, and three silver spoons, which he hid in a newly-dug grave at St. John’s Catholic Church.

Guglielmo moulded bullets when his uncle was away from home, insisting that he had acted alone. On 9 January, he slipped the pistol into his pocket as he and his uncle left home and headed towards Priors Marston.

At Williamscote, he approached his uncle from behind, placed the muzzle of the pistol close behind Giovanni’s ear and fired one barrel. ’The old man fell on the instant, as he supposes, without being in the slightest degree conscious whose hand caused his death.’

No member of his family visited him as he languished in custody. When his body was cut down, Guglielmo Kalabergo was buried in the area of the prison set aside for ‘those who die at the hands of the common hangman.’

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

https://www.newspapers.com/article/manchester-weekly-times-and-examiner-kal/178499526/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/hull-evening-news-attempted-escape-and-c/178500324/

Leave a comment