Hylas Parrish, an 18-year-old apprentice shoemaker, first met Charles Callaghan at Vauxhall Gardens in the summer of 1813, when he attended a fete held to celebrate the victory of Britain and her allies, Spain and Portugal, over Napoleonic France in the Battle of Vitoria.

At the fete, Parrish paid a penny for a ride on a swing, Charles Callaghan sat next to him, and the pair struck up a conversation. When the men finished their ride, Callaghan suggested that Parrish go with him, and ‘they have some fun among the people,’ Parrish had travelled to Vauxhall Gardens alone. With no plans for the evening, he agreed to accompany his newfound friend.

Parrish didn’t return to his family’s home until around five o’clock the next morning. His father flew into a terrible rage when Hylas got home, demanding to know what he had been doing all night and why he was only returning at such an hour. Hylas, in turn, raged at his father, and the older man, ‘in his passion threw a shoemaker’s knife at him.’

Hylas ran from his father’s house and sought out Callaghan, finding his friend in a tavern in Vauxhall. Callaghan revealed that he was a gentleman’s servant, but for the time being, he was unemployed.

After about a week, Hylas Parrish and his father became reconciled when the senior Parrish located his son and asked him to return home with him. ‘Unfortunately, however, the seeds of loose habits had become so planted in him, and he was so much attached to Callaghan, that he finally left his father’s house.’

Callaghan and Parrish then took lodgings in the Walworth neighbourhood; the rent for each man was two shillings a week. It was while at the Walworth residence that one day, Callaghan returned with ‘a number of silver spoons, tea tongs, and a variety of valuable articles.’ Parrish pressed Callaghan on where he obtained the items.

At first, Callaghan would not say, before eventually confessing that the previous evening he had broken into a house on Union Road, Clapham, belonging to a Mr. Taylor, a gentleman who had previously employed Callaghan. The thief boasted how easy it had been; having worked there, he knew precisely where anything of value could be found.

Initially horrified by Callaghan’s actions, Parrish was persuaded to join his friend when Callaghan revealed how easy it was to break into and make off with a few valuable trinkets. The pair purchased pistols, but Parrish revealed that the weapons were too large to be concealed on their bodies, and they had to cut the barrels down.

The two men robbed an acquaintance of Parrish, a cobbler named Moxhay, of four pairs of shoes. Callaghan was wearing a pair of shoes stolen from the cobbler when the pair committed their final crime.

Charles Callaghan knew the Vauxhall home of the Gompertz sisters very well, having, as with the Taylor residence, having previously worked there for a time. Unfortunately, I was not able to establish how many sisters there were; some sources state two, others three. Also, their names remain unrecorded.

Callaghan and Parrish left Walworth suitably equipped for their criminal enterprise; they each carried a pistol, as well as ‘a chissel, and various implements necessary for house-breaking.’

They reached Vauxhall at around midnight, it was the middle of December 1813, and both wore thick coats against the winter cold, which was also helpful for concealing their pistols and housebreaking tools.

As they crossed the road towards the Gompertz’s house, they met a passerby who later gave the police a somewhat uncertain description of the pair. Using the ‘chissel,’ they removed the padlock from the garden gate. Approaching the house, they realised that some members of the household were still awake. The Gompertz sisters’ cousin shared the house with them, as well as three female servants, a footman and Moses Merry, the butler. Merry slept in a room adjacent to the pantry near the kitchen. Every evening at eleven o’clock, he would take the musket which he kept in the pantry, fire it, then reload before retiring for the evening.

Callaghan and Parrish retreated to a local hostelry when they learned that the household had not yet turned in for the night. They returned to the house between three and four o’clock, confident that the family were deep in their slumber.

The two men removed a piece of glass from the kitchen window. One of them reached inside the room and removed a bell which was placed there for the purpose of giving an alarm. They managed to open the window, but it was too small to admit Callaghan.

Parrish was slighter than Callaghan, so he removed his overcoat and a second layer and squeezed through the opening. Parrish stood silently, listening to hear if he had roused anyone. When no alarm was raised, he moved swiftly to the door and let his accomplice inside.

On entering the house, Callaghan removed a pair of shoes with large nails that he had stolen from Moxhay’s shop to avoid making too much noise. They had only just begun to search the property when they heard a sound that made them believe that a member of the household had discovered them.

The two men halted their search, drew their pistols, and waited for a moment. After a nervous wait that seemed to last an eternity, they struck a light. A cat moved warily from view; they assumed it was this cat that they had heard and not a member of the household.

Callaghan, having worked for the Gompertzes, directed Parrish where to look. In the pantry, they found silver spoons and plates that lay unwashed from the previous evening’s meal. They gathered up the items along with other items of value. Then Callaghan spied a pair of large salvers, and he and Parrish debated whether they were silver or plated. The salvers were too large to be carried through the streets, and reluctantly, they left them behind.

Then Callaghan remembered the butler. Moses Merry slept next to the pantry. He owned a watch, which Callaghan desired. He instructed Parrish to search among the butler’s clothes for it.

As Parrish hunted for the watch, Merry rolled over in his bed, disturbed by the burglar. ‘Hiss, cat,’ he said, thinking the same cat the two intruders had been disturbed by had broken his sleep.

Suddenly, Moses Merry was awake. He leapt from his bed. ‘Give it to him,’ Callaghan shouted at his cohort. Parrish fired his pistol, but the ball missed its mark. Callaghan chased after Merry, placed the pistol barrel next to the butler’s head and fired. Unlike his confederate, Callaghan’s shot did not miss. The report of the pistol woke the household.

The two thieves fled from the house, leaving Merry’s watch behind. Callaghan did not have time to collect his shoes; he ran barefoot down the street, shouting accusations of cowardice at Parrish. Parrish admitted that he had no intention of shooting Merry and deliberately fired wide of his target.

The two men halted briefly; Callaghan wanted to return to the house, retrieve the salvers and make sure that Moses Merry, a man who knew them and could identify both Callaghan and Parrish, was dead.

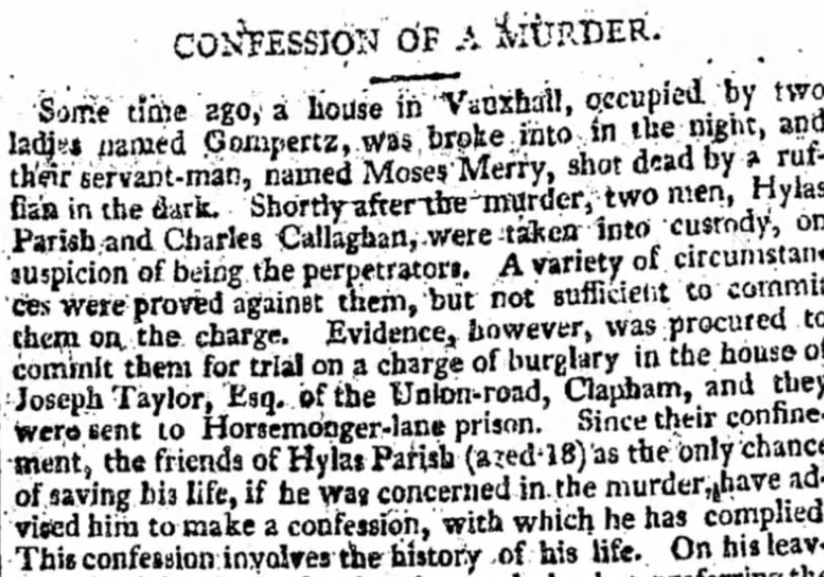

The Morning Chronicle, Friday, 11 February 1814

They started to retrace their steps towards the Gompertz house when they heard a bell ringing as an alarm; they knew their crime had been discovered. When they got on the road, they moved slowly so as not to arouse suspicions. They headed back to Walworth via South Lambeth rather than their usual route through Kennington Lane.

The pair reached their lodgings at about five o’clock, let themselves in, and went to bed, without their landlord being aware they had been out all night.

In the days following the murder of Moses Merry, the incident was discussed at length in the newspapers and by the general public. The two men decided to escape the country until the heat had died down.

They headed to Gravesend with the intention of joining the East India Company. While in Kent, Callaghan read a quote in a newspaper that a police officer named Goff was confident that the killers would soon be under lock and key. Callaghan told Parrish that he wished to shoot Goff. Aborting their attempt to get to India, the pair returned to London after selling some of the stolen property in the coastal town.

The two men were captured soon after returning to the capital. They were detained at Horsemonger Lane Prison. Hylas Parrish received from acquaintances, and possibly his father, who persuaded him that the only way he could escape the noose was by turning King’s Evidence and testifying against his erstwhile comrade.

The Caledonian Mercury, Monday, 21 February 1814

Charles Callaghan went to trial on Monday, 7 February 1814. Mr. Nares, the Magistrate of the Public Office, Bow Street, was the presiding judge. Hylas Parrish, having turned King’s Evidence, confessed to his role. As Parrish spoke, Callaghan frequently interrupted, stating that Parrish had been the one who had shot Moses Merry.

The Bristol Mirror, Saturday, 9 April 1814

Despite his outbursts, Callaghan was swiftly convicted. He was sentenced to be hanged at Horsemonger Prison.

Callaghan went to the gallows still maintaining his innocence in the murder of Moses Merry. The fate of Hylas Parrish is lost to history.

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

https://www.exclassics.com/newgate/ng775.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vauxhall_Gardens

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-caledonian-mercury-confession-of-a-m/179414970/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-chronicle-murder-of-moses-me/179415170/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-chronicle-murder-at-vauxhall/179415286/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-western-flying-post-or-sherborne-a/179415389/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-morning-post-callaghan-and-parish/179415640/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-bristol-mirror-the-execution-of-char/179440708/

Leave a comment