By Jim Helvey, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53005166

South of the Canadian border, in the Two Medicine area of Glacier National Park, stands the imposing feature that is Rising Wolf Mountain. The author James Willard Schultz named the mountain in honour of his friend Hugh Monroe, a former Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and American Fur Company (AFC) employee.

Hugh Monroe was born at L’Assumption, Montcalm County, Quebec, on 25 August 1799, although some sources state he made his entrance into the world in 1784. His father, also named Hugh, was a captain in the British Army stationed in Canada, and his mother was Angelique de la Roche, a French emigre with royalist loyalties.

Monroe’s paternal grandfather, John Munro, was born in Ross-shire in the Scottish Highlands. He moved to North America during the Seven Years’ War, arriving in 1756, and seeing action at the siege of Louisbourg in 1758 and then the following year at the Plains of Abraham. After the war, Munro developed a close friendship with Simon McTavish, the chief founding partner of the North West Company (NWC), the HBC’s biggest rival.

During the American Revolution, John Munro remained loyal to the crown. Captured by Colonial forces at Albany, while on a mission to recruit men to the 84th Regiment of Foot, Munro was sentenced to be hanged. He escaped his imprisonment and fled across the border to Canada and safety.

Hugh Jr, the subject of this post, was one of ten children, three of whom died in infancy. After attending school in Montreal, Monroe later spent four years training for the priesthood. Instead of donning vestments, the teenage Monroe joined the Hudson’s Bay Company as an apprentice clerk.

Hugh went west to Edmonton House as part of a group that travelled in five boats laden with goods for trade with the natives of the country that would become today’s province of Alberta. Before leaving, his mother gave Hugh a travelling kit that included a prayer book; his father equipped Hugh with a pair of silver-handled pistols.

Hugh and his comrades left Montreal in May 1814. The Baymen travelled along the Ottawa River, Georgian Bay, Lake Superior, and Rainy River, before arriving at Fort Garry (today’s Winnipeg, Manitoba). The party reached York Factory on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in September, where they overwintered.

York Factory, built on the north bank of the Hayes River, was one of the oldest of the HBC’s posts. It was constructed in 1684. York Factory was the Company’s Northern Department headquarters from 1821, when the HBC merged with the NWC, until 1873.

When Hugh reached Edmonton House in the summer of 1815, he was under the command of the chief factor Richard Hardesty. Hardesty had been acquainted with Hugh’s father and grandfather.

While on a sojourn at Rocky Mountain Fort, on the confluence of the Clearwater and North Saskatchewan rivers, in present-day west-central Alberta, Monroe was offered the opportunity to spend a year living with the Piikani (Peigan) Nation, part of the Blackfoot Confederation. The plan was for Hugh to learn the customs of the Piikani as well as their language to become an interpreter for the HBC.

The current interpreter, Antoine Bissette, a French-Iroquois mixed-race man, whose Cree wife knew a little of the Blackfoot language, was, in the words of the author Warren L. Hanna, ’totally inadequate’ in the role.

Monroe was to share the lodge of the Piikani chief Lone Walker (Ni-to-wa-wa ka). Lone Walker reputedly had sixteen wives, presumably not all at the same time. Sinopah (Kit Fox Woman) would later marry Monroe. Lone Walker also possessed two pet bears, which followed him on his walks around his village.

Monroe travelled in a caravan of about 800 lodges after leaving the HBC’s post. He spent his first winter amongst the Piikani on the Sun River in Montana. Monroe became close friends with Lone Walker’s son, Red Crow; the two youths were of a similar age. Monroe saved Red Crow’s life when he shot and killed a charging grizzly bear.

The following spring, the party hunted in the Yellowstone country. They overwintered at the mouth of the Marias River. They returned to Edmonton House laden down with furs the following spring. Monroe reported to his superiors that they had encountered no American traders in the Yellowstone country.

According to Schulz, Monroe took part in skirmishes against other indigenous groups. On one occasion, Monroe and the Piikani encountered the famed mountain man Jim Bridger, along with a dozen of his comrades and a party of Shoshone, avowed enemies of the Blackfoot Confederation. Monroe managed to convince his allies not to destroy their adversaries.

It was around this time that Monroe married Sinopah; they had ten children together, one of whom died in infancy. One of Monroe and Sinopah’s sons, Felix, also served as an HBC interpreter and fulfilled the same function for the Palliser expedition. Two of his brothers, Oliver, or Olivier, and William, also served in the expedition.

Two of his daughter Amelia’s sons served as scouts with Colonel George A. Custer’s 1874 Black Hills Expedition, and after the rout of the Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, acted in a similar role under General Nelson A. Miles.

After leaving the Piikani, Hugh served at Edmonton House until 1823; his contract with the HBC was terminated at the same time that an accusation of theft of liquor was levelled at him.

Upon leaving the HBC, Monroe, who had by this time received the sobriquet Rising Wolf from his old friend Lone Walker, eschewed the opportunity to return to his birth family in the east and instead became a free trapper.

While still working for the Company, Monroe began a long association with the Kootenai people, like the Shoshone and many other tribes, including the Absaroka and Cree; the Kootenai were enemies of the Piikani.

By the early 1830s, Hugh Monroe had returned to work for the HBC. The American Fur Company had just constructed Fort Piegan on the Marias River. Monroe had visited this post on his return to Edmonton House to purchase supplies and perhaps glean information as to the American company’s plans.

Monroe again left the HBC to become a free trapper on Lower St. Mary Lake; close by were his Kootenai friends. Hugh and his family lived a nomadic life. In 1853, he served as a guide and interpreter for Montana governor Isaac Stevens.

Stevens’ party’s most pressing task was to find a railroad route through the Rocky Mountains. Governor Stevens was informed of a possible pass through the mountain known as Marias. Little Dog, a Piikani chieftain, gave Stevens a description and location of the pass.

Two scouting parties were sent out to search for the elusive pass; one went from the west in October 1853, and the second group of men ventured south from the area around St. Mary’s Lake the following May. Neither set of pathfinders was able to find the pass.

Monroe warned Stevens against making any further attempts to find the pass, stating that hostile Indians might ambush his men. Little Dog had already informed Stevens that the Indians did not use the area around the pass, a fact Monroe was cognisant of. Why Monroe did not wish to lead Stevens’ men to the pass is unknown.

John Stevens, an employee of the Great Northern Railway Company, discovered the Marias Pass in December 1889. A statue of John Stevens now stands atop the summit of the Marias Pass.

Monroe joined the American Fur Company in the 1850s. He lived at the Fort Benton trading post with Sinopah and four of their children; their oldest son, John, and his wife, Isabel, and their daughter, Amelia, with her husband, the post tailor, Thomas Jackson and their children, the couple’s youngest daughter, Lizzie, and their bachelor son, Frank.

In 1864, Andrew Dawson, the Fort Benton post manager and father figure to Jerry Potts, a man who would leave an indelible mark on the Canadian prairies, retired to his Scottish homeland.

With the change of management, the Monroes left Fort Benton, driving a herd of 90 horses towards Glacier National Park. In the Two Medicine Country, Amelia’s two sons shot and wounded a grizzly bear; the bear continued to charge and would have killed the oldest boy if Hugh Monroe hadn’t arrived in time to shoot the animal.

They spent time in the Two Medicine Valley, where a band of Kootenai joined them. Soon after, they moved on to Lower St. Mary Lake, where they erected three lodges and spent time trapping beaver. As the beavers they trapped started to dwindle, the family moved to the Upper Lake.

The family was eating a supper of a young moose shot earlier by Lizzie, when the barking of dogs alerted them to the presence of unwelcome visitors. John and Frank snatched up their rifles and dashed into the darkness, where they discovered a group of Assiniboine men were dismantling the corral and trying to drive the Monroes’ horse herd away.

Hugh instructed the women to run through the treeline and head toward a ford in the river. Hugh, Thomas Jackson and his two sons grabbed their firearms and joined Frank and John in the pursuit of the raiders. Lizzie, ignoring her father’s direction, took up a rifle and followed on behind the men.

The Assiniboine war party greatly outnumbered the Monroes and escaped with all but two of the horses. Heaping more misery onto the Monroes, the Asiniboines ransacked the lodges, casting aside four women’s saddles; they took anything of value and set the lodges ablaze.

The following morning, with Amelia and Sinopah on the two remaining horses, the family headed towards Two Medicine Lake, hoping to find their Kootenai allies. However, the Kootenai had moved on, and it wasn’t until the next afternoon that they discovered their friends on Little Badger Creek.

The Kootenai fed the Monroes and supplied them with horses and equipage. The Monroes moved south, where once more they were reunited with the Piikani. They soon arrived back at Fort Benton, where Thomas Jackson decided that he was unsuited to the life of a trapper and resumed his previous career as post tailor.

Hugh, Frank and John Monroe refitted with traps and ammunition bought on credit, and along with the two Jackson boys, headed towards the Belt mountains. They returned to Fort Benton in November with six packs of beaver pelts.

This cycle continued until the early 1870s when Hugh’s feet started to get itchy. He and his family, including Frank’s new Cree wife, headed north to the headwaters of the South Saskatchewan River. The Jacksons declined to go along with their relatives; Tom Jackson wanted to head down the Missouri to Fort Buford, where he was confident he could find gainful employment.

In the 1870s, trappers discovered that the pelts of timber wolves were proving profitable. It was a group of these wolfers from south of the Medicine Line that had been responsible for the Cypress Hills Massacre in what is today the province of Saskatchewan.

Hugh Monroe and his family collected 300 wolf pelts in their first season in the business. They sold the hides for $5 each at Fort Benton. While some of the wolfers, such as those men involved in the killing of Assiniboines in the Cypress Hills, resorted to poison, Monroe devised another way of catching his prey.

He built oblong, pyramidal log pens of approximately 8 feet by 16 feet at the base and 8 feet in height. He placed the top layer of logs about 18 inches apart. The wolves would climb to the top of the slope and then jump down the narrow opening to snatch the meat that had been placed inside as a lure. Unable to escape, the wolves would be killed and skinned when Monroe and his sons returned in the morning.

The Monroes stayed in the area around St. Mary Lakes for the better part of a decade. It was towards the end of their time there that Sinopah died. It was in this same period that Monroe first encountered the writer James Willard Schulz. Monroe told Schulz, who had just returned to Montana from his former home in New York, that he never returned east to see his family. He had intended to visit his parents, but had kept deferring it; he had received letters informing him of the death of his parents. He received a further missive from an attorney, saying that he had been left a considerable amount of property and that he should travel to Montreal to obtain it.

The company factor at Mountain Fort was heading to England on leave, and Monroe gave the factor power of attorney to act on his behalf. The factor never returned, and Monroe lost his inheritance.

The decline of Hugh Monroe began in the 1880s. He became destitute and relied on friends and family for help. In the summer of 1888, Monroe headed to Fort Macleod to petition the HBC for financial support. He enlisted a pair of attorneys to draft a formal petition.

The petition greatly embellished the amount of time that Hugh had worked for the HBC and altered his date of birth, despite enlisting the support of Father Albert Lacombe, a Roman Catholic missionary who had brokered a peace treaty between the Cree and the Blackfoot and also persuaded Crowfoot, the eminent Blackfoot leader, not to participate in 1885’s North-West Resistance.

Lacombe’s letter noted that Monroe’s predicament was ‘his own fault. The money he made, was wasted by carelessness and foolishness. As he has only a short time to live, I thought to call to your charity and generosity in behalf of Hugh Mounroe. If you think advisable for the H.B.Co. To grant him something, it might be better to give him so much a month from the store.’

Despite the efforts of Father Lacombe and the attorneys, Hugh’s request for a pension was denied. Joseph Wrigley, the HBC’s trade commissioner at Winnipeg, wrote to Lacombe, informing the priest that he had instructed the officer in charge at Fort McLeod to make presents of food and clothing to Monroe occasionally.

Hugh Monroe moved back to the United States, where he spent the last four years of his life. He died on 8 December 1892. Chief Factor Richard Hardesty wrote: ‘For the last 20 years he has been in his dotage, and consequently little reliance can be placed on what he says.’

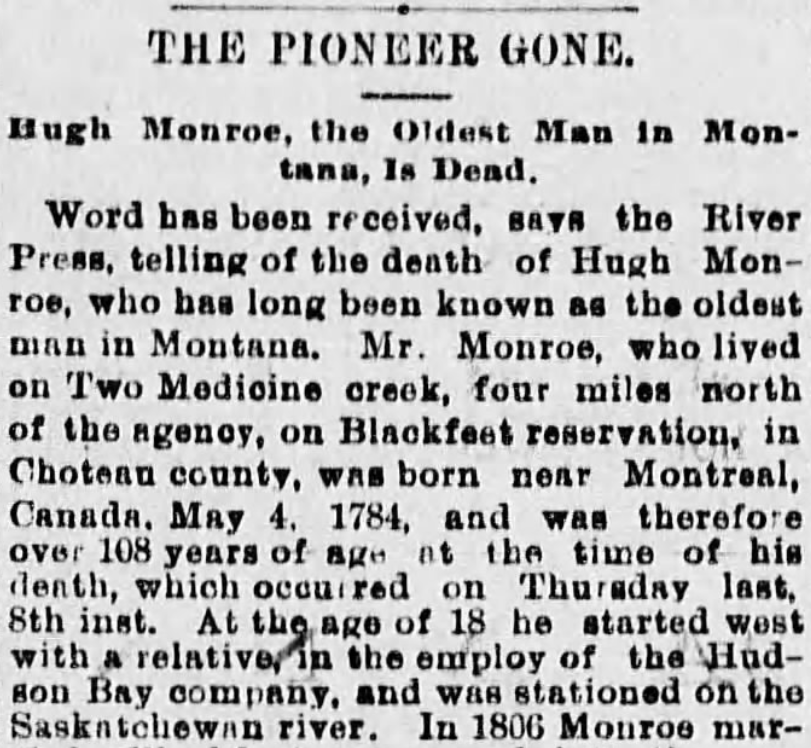

Hugh Monroe’s obituary appeared in the Independent-Record on 14 December 1892.

In the years before he died, Monroe had told journalists that he had been born in 1784, something he also claimed in the petition to the Hudson’s Bay Company. In an obituary published in Helena, Montana’s Independent-Record informed its readers that Hugh had been ‘the oldest man in Montana’. As we have seen, he was born in 1799 and was 93 when he died.

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography Vol. II By Dan Thrapp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_Monroe

https://bigforkeagle.com/news/2010/apr/08/sixteen-wives-and-the-garden-wall-15/

http://clanmunrousa.com/gen/getperson.php?personID=I22050&tree=1

https://www.summitpost.org/rising-wolf-mountain/219423

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=pACeCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Leave a comment