In this post, we are looking at five murders committed in the Cariboo region from 1862 to 1864.

Starting with the killing of Averena Rice Aka:

’The Scotch Lassie’

After 1861, musicians, magicians, actors and touring minstrel troupes from San Francisco began to spend time in the Cariboo goldfields entertaining the ‘settlers so wild, so miscellaneous,…a form of society so crude.’

Averena Rice, ‘formerly a beautiful and accomplished lady from San Francisco,’ also arrived in the Colony of British Columbia from California sometime in the early 1860s. More commonly known as ’The Scotch Lassie’, andmaking her livingas a prostitute, her beaten body was found beneath a mattress in her Williams Creek home, around noon on Tuesday, 20 September 1864.

The Victoria Daily Chronicle edition published on Sunday, 2 October, reported that Averena had been seen alive two hours before her body was discovered. It added that an unnamed German had been ‘lodged in jail pending the result of the coroner’s inquest.’

Victoria Daily Chronicle, Sunday, 2 October 1864

The same newspaper reported four days later that ‘John Collins, a miner,’ had been detained at Quesnelle Mouth on 27 September, and charged with Averena Rice’s murder. The Chronicle posited the theory that there had been three murderers, ‘who first ravished the unfortunate woman, and then smothered her with a mattrass(sic).’ The report added that ‘Gardner, arrested on suspicion of perpetrating the murder, was discharged.’ Gardner was possibly the man the chronicle had noted had been arrested and placed in jail after the murder was discovered.

Dr A.W. Black, a London-born physician, conducted a post-mortem on the dead woman and found that ’she had died from violence’. In its initial report of the murder, The Chronicle asserted that Averena Rice’s ‘skull appeared to have been beaten in with a club.’

On Friday, 30 September, the trial of the accused named in the Chronicle as simply ‘Baumgartner’ took place. Baumgartner and the man previously identified as Gardner are likely the same person. The Victoria Daily Chronicle probably did not have a reporter at the trial and received its information from observers in court. The location of the trial is also not recorded, but it was most likely held in either Williams Creek, Barkerville, or Lillooet.

John Collins, charged with murder on 27 September, was not tried for Averena Rice’s murder, and his name does not crop up in newspaper reports again; whether he made an appearance at Baumgartner’s trial goes unrecorded.

Baumgartner was seen in Averena Rice’s cabin on the morning she was murdered; the main piece of evidence linking the accused with the killing was that in his possession, he had an American quarter coin which, according to the prosecution’s principal witness, belonged to the dead woman.

A Frenchwoman known by the appellation ‘Old Curte’ testified that the quarter found on Baumgartner had previously belonged to Averena Rice, and she had seen it numerous times in the possession of the prisoner.

A juror rose and asked, ‘Old Curte,’ how she could recognise the coin. The witness replied that she did not know how she knew, but was sure it was the same coin.

George Walkem, acting for the defence, called as a witness a man who had played ‘freeze-out poker’ with Baumgartner and two other men on Sunday, two days before Averena Rice was murdered.

The witness told the court that, among the money gambled that evening, was a quarter with a hole in it, similar to the one found on Baumgartner. ‘On hearing this evidence the jury rose and stated to the bench that they were all agreed that there was no evidence before them to convict the prisoner, and acquitted him.’

As far as I am aware, nobody else was ever tried for the murder of Averena Rice.

Murder on Wright’s Wagon Road

Tom Clegg was a 28-year-old Ohioan, employed as a courier by the firm of E.T. Dodge & Co. The company had bases in both Lillooet and Port Douglas; they supplied the miners in the Cariboo with provisions: ‘our TEAMS and TRAINS are kept constantly running over the roads leading to the mines, and goods entrusted to our care will, if desired, be insured against loss and unnecessary delay.’ Ran the advertisements placed in the Victoria newspapers.

On Thursday, 20 August 1863, Tom Clegg was returning to Lillooet from Barkerville, where he had been dispatched to collect money owed to the company. Reports suggest that Clegg could have been carrying as much as $10,000 in gold dust.

Accompanying Clegg was Captain Joe Taylor. Taylor, in conjunction with Clegg’s brother Webster, ran the Seton Lake Steamer, which plied the waters between Port Douglas and Lillooet. On the evening of the 19th, the pair had stopped overnight at Williams Lake before continuing on the following morning. They halted for a brief repast at Murphy’s Stopping House.

The two men had ridden a short distance from Murphy’s. As they began the ascent of a small hill, they noticed a couple of men on foot, whom they assumed were miners. As the riders passed, the pedestrians, both of whom were wearing masks, grabbed the bridles of Taylor and Clegg’s mounts.

Joe Taylor exclaimed: ‘My god! Boys, what do you want, and what do you mean?’

Tom Clegg responded: ‘Joe, where are you?’

Taylor answered: ‘I am here- shoot him.’

The man who had grabbed Taylor’s horse drew his pistol and fired a shot, causing Taylor’s horse to shie, throwing Taylor from his saddle and knocking his attacker to the ground. Joe Taylor was quickly on his feet, ‘drawing his revolver he fired once at the scoundrel-the ball taking effect in his side, and the man fell.’

Taylor looked to see what had become of Clegg, and saw him lying prostrate on the ground. Seeing the second assailant advancing towards him, Taylor leapt on his horse, and one of the robbers fired his weapon, the ball striking the horse in the side, ‘causing him to become affrighted and run off with Taylor on his back.’

Joe Taylor, on his wounded mount, reached the next wayside inn, which lay about half a mile from the scene of the attempted holdup. He returned with some men from the inn to find Tom Clegg’s body on the trail. The Victoria Daily Chronicle reported, ‘Clegg was …found quite dead; one ball had passed entirely through his neck, and the other had entered his chest.’ The paper, which reported his murder eight days later on Friday, 28 August, went on: ‘Death must have been instantaneous.’

Victoria Daily Chronicle, Tuesday, 1 September 1863

The two attackers had searched Clegg’s pockets and saddlebags without success, unaware that the gold dust had been transferred to Taylor’s bags. Again from The Chronicle: ‘the robbers got nothing in return for their fearful load of crime with which they have freighted their consciences.’ One of the assailants, probably the one shot in the side by Taylor, dropped his pistol and knife in his haste to get away.

In the days after Tom Clegg’s murder, E.T. Dodge posted a reward of $2,000 for the capture of the killers. Eventually, the reward would climb to $6,000 when other concerned citizens made contributions.

By 10 September, The Daily Chronicle was reporting that the two suspects were believed to have fled the country, as no sign of them had been found. The same report had earlier evinced great hope that Dodge would be able to capture the two ‘scoundrels’ as he ‘was formerly an officer in California, and the business of hunting down highwaymen is not new to him.’

A few days later, one of the suspected murderers was caught. He approached two prospectors and asked for something to eat; the two men invited him to their camp. As the man sat eating his meal, Donald McLean, the former trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), entered the camp and arrested him. We encountered McLean in a previous post, and he will feature in a future one.

The arrested man gave his name as Robert Armitage and said that he arrived in Victoria from Liverpool in June 1862. Armitage was said to be ‘half-starved’ and in his pocket was a half-eaten raw potato. The prisoner was transported to Lillooet, where a pistol identified as Tom Clegg’s was found in his possession.

By the time the prisoner reached Lillooet, the press had begun to refer to Armitage as William, rather than the original Robert. He confessed to having been involved in the murder, saying that he held Clegg down while his co-conspirator, now identified as Fred Glennard, fired the fatal shot.

The search was now on to find Armitage’s accomplice, who, it was believed, had been wounded by Joe Taylor. There were reported sightings of Glennard, an American, in the vicinity of the Thompson River.

On 15 September, near the mouth of the Nicola River, a body, ‘swollen and bruised was found washed ashore on a sand-bar, near Cook and Kimball’s ferry.’ It was believed that the body had been in the water for about nine days. The body was identified as that of Glennard by the clothes he was wearing and the tattoos on his arms. It was presumed that Glennard had drowned while trying to cross the Thompson to make his way to the Oregon Country.

The trial of William Armitage took place at Lillooet Assizes on Friday,16 October 1864. The trial was presided over by Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie, Chief Justice for the Colony of British Columbia. H. P. Walker, Queen’s Counsel (QC), handled the prosecution, while the man tasked with defending Armitage was Mr. Barnston.

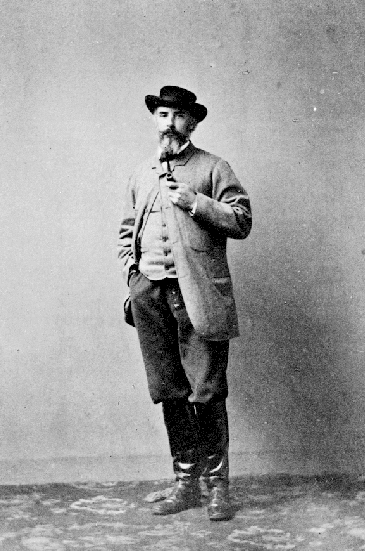

Sir Matthew Bailie Begbie, first Chief Justice of the Crown Colony of British Columbia.

Joe Taylor was the first witness to give evidence, followed by John Hancock, who accompanied Donald McLean when the erstwhile HBC trader had apprehended Armitage at the prospectors’ camp.

McLean, Webster Clegg, brother of the slain Tom, along with Sacramento Gonzales, a gunsmith, all swore that the gun that Armitage was carrying on his person when he was arrested had belonged to Tom Clegg.

After the prosecution rested, Mr. Barnston reminded the jury that Armitage had had numerous chances to escape after his capture but had chosen not to do so. Barnston concluded by telling the jury that if they had any doubt, then they must acquit the prisoner. A speech that brought Armitage to tears.

Judge Begbie summed up the evidence before discharging the jury.

The jury was out of the courtroom for only a few minutes. Armitage had recovered his composure in time to hear the jury announce a guilty verdict. The prisoner ‘was asked…why sentence should not be pronounced on him? He rose…and said in most mournful tones, that he had not perpetrated the deed; he was led into it…he had told Glennard not to shoot…he informed of the whereabouts of Glennard; he was young, would reform and asked for mercy.’

Judge Begbie, who, after he died in 1894, would earn the sobriquet ‘The Hanging Judge’, addressed Armitage: ‘the punishment…was not alone what justice and the country required; they required an example to deter others and by executing the sentence of the law on one they afforded protection to hundreds, nay thousands who had to traverse the country with or without treasure…heartrending as the duty was that devolved upon him he must sentence him to be taken hence to the place whence he came, and from thence to the place of execution and hanged by the neck till he was dead, and might the Lord have mercy on his soul.’

The Chronicle informed its readership that ‘the prisoner here gave way to his grief, and there glistened a tear in the eye of many in the room, as he was led back to the gaol.’

William Armitage, found guilty of the Murder of Tom Clegg on Wright’s Wagon Road on 28 August, was executed at eight o’clock in the morning on 25 November at Lillooet. The warrant for his execution had arrived from Victoria the previous evening. ‘On the scaffold he stood firm and erect, and did not exhibit as much emotion as the most unconcerned spectator. He simply said, “The sentence is just; I deserve to die.” He seemed to die very hard; his neck not being broken by the fall.’

The Chronicle added in a postscript that the hangman was named ‘Whistling Dick’. How he gained that appellation, I’m not sure.

Boone Helm

Unknown(Life time: 1828-1864), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Boone Helm in the Cariboo

Wherever Boone Helm ventured, death seemed to be his companion. Helm was born in Lincoln County, Kentucky, on 28 January 1827. He moved with his family to Missouri when he was a child. According to The Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, in Missouri, ‘he matured as a wild and unruly young man, inclined towards bowie knives, horseplay, alcohol and rough companions.’

In 1849, Boone travelled to California with at least two of his brothers. One of whom, Fleming, was killed in a dispute that took place during a card game. Fleming’s killer was then subsequently killed by David Helm.

Back in Missouri, Boone undertook a short-lived marriage to Lucinda Browning, which produced a daughter, but soon ended when Lucinda sued for divorce, ‘cheerfully assented to by her errant husband.’

After the divorce, Boone Helm killed Littlebury Shoot when the latter refused to travel to Texas with Helm. Shoot was a neighbour of Helm’s; in some sources, he is listed as a cousin. It seems that initially, Shoot had agreed to go to Texas with Helm, before reneging on the deal, whatever the facts, Littlebury Shoot is generally viewed as Boone Helm’s first killing; he would not be the last.

Helm fled after the killing, but was captured in Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma) by agents hired by Littlebury Shoots’ brother William. Legal delays and changes of venue resulted in his being held in custody beyond the limit allowed by law. Upon release, Helm headed back to California, where he possibly stayed for a time with some of his equally obnoxious cousins.

After a killing in California, Helm headed to the Dalles, Oregon, in the spring of 1858. He planned to travel the Overland Trail east with some companions later in the year; one of his party was so unnerved by Helm’s incessant boasting about his criminal past that he returned to the Dalles.

The man who had turned back undoubtedly made the correct decision. Helm’s company had a skirmish with Indians on the Raft River, Idaho; a second engagement near the Bannack River saw one of the travellers killed.

Winter closed in on the Helm party. When spring arrived, only Boone Helm remained alive. He was found by a group of men led by John W. Powell feasting on the remains of one of his dead comrades.

Powell took Helm to Salt Lake City, where the Kentucky-born desperado was accused of killing a pair of locals and joined a local gang of horse thieves. Venturing to California once more, another killing was attributed to him. Returning to Oregon again, ‘where he perfected himself at road agentry, and, it was whispered, committed several murders.’

Which led him to cross the Line into British Columbia.

On 10 August 1862, Victoria’s Daily Evening Press reported on the Murders of three men; two of whom, David Sokolosky and Herman ‘Dutchy’ Lewin, were former residents of Victoria and would have been known to much of the newspaper’s readership. The third man was named in the article as Rougier; his name would later be rendered as Reucheir and Reauchier in other articles. The Weekly British Colonist of 12 August identified him as Charles Beaucheir, ‘until recently a trader at Nanaimo, and last a packer of goods to Cariboo.’

On 18 July, Sokolosky, Lewin and Beaucheir left Antler Creek in the company of two Miners, W.T. Collinson and Tommy ‘Irish Tommy’ Harvey, heading for the Forks of Quesnelle. The five men journeyed together to Keithley Creek. Sokolosky and his two companions, described in a letter that Collinson had published in the Colonist in 1864, ‘as two Frenchmen’, stopped for dinner. Collinson and Harvey continued for another three miles before halting for their meal.

The following day, Sokolosky and his companions left Keithley Creek and reached the North Fork Bridge at around 5 o’clock. They enquired about the conditions of the roads that led to Forks of Quesnelle. A waiter in the wayside inn they stopped at informed them that the lower road was muddy.

The men decided to take the rough and little-used mountain trail. After Sokolosky, Lewin and Beaucheir had announced their intention to take the mountain trail, three men who had been sitting in the house got up and left. The three strangers crossed the bridge and rode off along the mountain trail.

A short time later, Sokolosky and company left; they were hoping to reach the Forks of Quesnelle by dark and spend the night there. As expected, when they mounted up, the men headed out along the mountain trail.

That evening, several men who had encountered Sokolosky, Lewin, and Beaucheir on the trail from Antler Creek arrived at the Forks and were surprised the three companions had not arrived. By the following day, they still hadn’t arrived, and their friends were growing worried. It was common knowledge that the men were carrying ‘treasure’ with them; contemporary newspapers put the sum at $18,000. By 1864, W.T. Collinson had inflated the figure to $32,000.

Sunday passed without news of the three men. John Boas of the New Westminster firm Levi & Boas set out towards the North Fork Bridge on Monday morning. He arrived at the bridge without having gained intelligence concerning the whereabouts of the three men.

Boas persuaded a group he met at the North Fork Bridge to comb the mountain trail, while Boas rode along the lower road looking for signs.

The men searching the mountain trail had travelled about three miles from the North Fork Bridge when ‘they detected blood and other indications of a suspicious character, and discovering three trails seemingly made by dragging bodies over the ground, leading down the hill, in the direction of the North river; they followed, and…they discovered the three bodies of the murdered men.’

The Weekly British Colonist, Tuesday, 12 August 1862

The searchers left the bodies where they lay and rode on toward the Forks, where they announced that they had found the missing companions. A party of about thirty horsemen set out from the Forks to recover the bodies; they returned with the dead men at around 8 o’clock that evening.

W.T. Collinson was at the Forks ‘we…saw the murdered men brought in. They had made a brave fight, every man’s pistol was empty and each man had a bullet in his head.’ Already, suspicions were being voiced as to who the killers were. The Reverend Arthur Browning, who had met the party as they brought the murdered men to the Forks, said: ‘Who was the murderer, or who were the murderers? Everybody said in whispers that it was Boone Helm, a gambler and cutthroat who had escaped the San Francisco Vigilance Committee.’

The Corpses of David Sokolosky, Herman Lewin and Charles Beaucheir were stored in an empty house until the next morning. The bodies were washed, and the wounds examined by Dr. Moses, another man with connections to Victoria. After the physician had finished his examination, the bodies were covered with shrouds and laid out to await a coroner’s inquest. Tin coffins were ordered for both Lewin and Sokolosky, ‘with a view to their convenient removal by their friends at any subsequent period.’

On Tuesday, 29 July, the day after the discovery of the ‘Horrible Murders’, a public meeting was held in the town of the Forks of Quesnelle, in which all inhabitants of the town and the surrounding area were in attendance.

The Reverend Arthur Browning, unanimously elected as chairman ’stated that a dreadful murder of three esteemed citizens had been committed in our midst; and, as there was no magistrate or any other authority in the place or neighborhood to assist in the search of, and pursuit after the murderers, it became necessary for every inhabitant of the country to empower somebody to act in this manner with the least possible delay’.

Committees were appointed and resolutions were passed, including: ‘Resolved, that we, the citizens of the Forks of Quesnelle, in the absence of all officers empowered with the necessary authority to issue a warrant for the arrest of suspected parties, at the time when one of the most atrocious murders has been committed upon three respectable traders and packers immediately in the vicinity of this place, do propose to dispatch four armed men in pursuit of the supposed murderers, who, we have from circumstancial evidence every reason to believe, have left for the lower country, and with due vigilance can be taken…and furthermore resolved, that a sufficient collection be immediately raised for the purpose of defraying the expenses of the four men to be dispatched in pursuit.

The Weekly British Colonist, Tuesday, 19, 1862

On the same date, Arthur Browning, acting as coroner in the absence of an official one, held an inquest into the deaths of Sokolosky, Lewin and Beaucheir (rendered in the coroner’s report as Rouchier).

Browning found that ‘Charles Rouchier received four wounds from pistol shots; that H. Lewin received two pistol shots; and that David Sokolosky received three pistol shots. That said pistol shots caused their death on the instant, or at the time, namely, on Saturday 26th day of July, 1862, between the hours of 5 and 7, p.m…the said pistol shots were fired by the hands of some person or persons unknown.’

In the same report, the four authorised to hunt the killers were named; they were ‘Messrs. E. Griffin, Hankin, Fordman, and Charles Francois.’ Hankin, may be Philip Hankin, who served in the Royal Navy and helped survey the coast of British Columbia. After he left the navy, he walked from Yale to Barkerville, intending to try his hand at prospecting. He failed to make a living in the goldfields; returning to Victoria, he served as Superintendent of Police for the Colony of Vancouver Island. He later served as colonial secretary in British Honduras. Hankin Island, off the coast of Ucluelet, is named for him. As is Mount Hankin in central Vancouver Island.

The Weekly British Colonist of Tuesday, 12 August, provided more details from the inquest: ‘Sokolosky, who was a powerful young man, appears to have struggled violently. His revolver was found lying cocked at his side, and there were marks of fingers pressed heavily on the throat. His shirt was found partially stuffed into his mouth to serve as a gag, and thus prevent his cries from being heard. He had also been beaten on the head with a weapon—probably a revolver. The bush near the spot where Sokolosky’s body was found bore signs of the fearful death struggle he must have engaged in with his murderers, and a considerable quantity of blood was observed on the trail. Lewin and Beaucheir looked natural, but Sokolosky’s features were sadly distorted and bruised.’

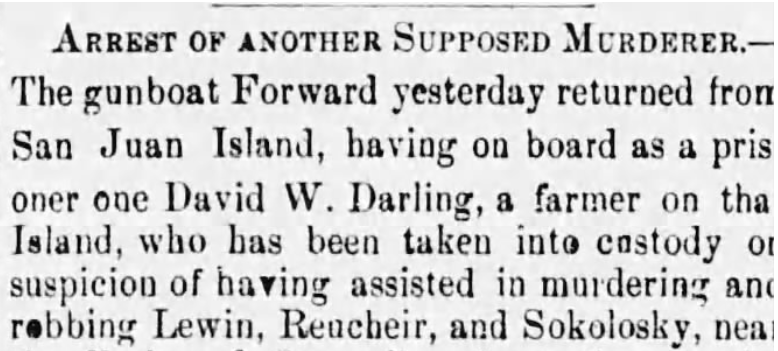

The morning of Friday, August 15, saw the appearance of David W. Darling in the Police Court in Victoria. Darling was a farmer and former captain of the schooner Black Hawk, which plied the waters between San Juan Island and Victoria.

The Americans had arrested Darling on San Juan Island; he was handed over to Lieutenant Lascalles, commander of the gunboat Forward, and transferred back to Victoria aboard that vessel.

Police Superintendent Horace Smith was sworn in and told the court that information the police had received would prove that the prisoner had been seen in company with the three murdered men. Smith added that Sokolosky, Lewin, and Beaucheir had employed Darling to carry their gold dust. The superintendent stated that Darling had passed along the mountain trail a few hours before the three slain men had. Smith concluded by asking that Darling be remanded in custody, to enable Smith to find the necessary witnesses.

The Weekly British Colonist, Tuesday, 19 August 1862

He said that day he passed several men who, he presumed, were carrying gold dust. One of these men was Beaucheir, holding his gold dust in a gunny sack. A little further up the trail, he passed Lewin. He alleged that Lewin, ‘a Jew I suppose,’ offered him $15 to carry his saddlebags. Darling said he carried Lewin’s bags to Keithley Creek.

He said the next day, the day of the murders, he rose and headed alone to Beaver Lake. He eventually reached New Westminster, which he called ‘Queensboro’ via Williams Lake, Alkali Lake, Big Bar Creek and Lillooet Flat.

’The Police magistrate subsequently, upon application of Mr. Bishop, who has been retained to watch the case for the prisoner, consented to liberate the accused on bonds of two sureties of £500 each and himself in £1000; but up to last night we heard of no responsible party coming forward to go his bail.’

The following Monday, Henry Dierick, from Yreka, California, appeared in the Police Court. He had ‘been arrested on suspicion of being concerned in the late murders at Cariboo.’ He was released from custody, without ‘the least stain on his character.’

The next day, ‘The Police Court Room was again crowded…by spectators anxious to hear…the charges preferred against David W. Darling…who stands charged with the murder and robbery of three men,’

Again, Horace Smith, in the absence of key witnesses, asked that the prisoner be remanded into custody.

Mr. Bishop opposed Smith’s motion, arguing that there was not a ‘scintilla of evidence to connect his client with the commission of the horrid crimes.’ Darling was returned to the gaol, but not before the magistrate acceded to his request to be able to write a letter to his wife.

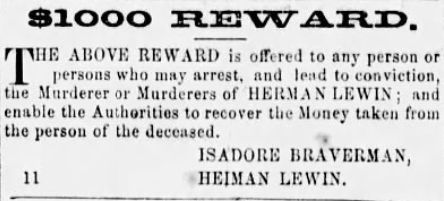

It was around this time that Herman Lewin’s brother, Heiman, and his business partner, Isadore Braverman, posted a reward of $1,000 in the Victoria newspapers. The reward would be paid on the conviction of Herman Lewin’s killers and the return of the gold dust.

Daily Evening Press, Friday, 19 September 1862

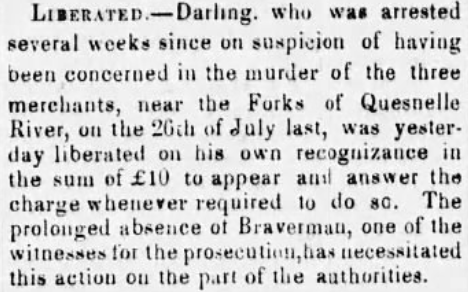

Darling appeared in court once more on 2 September. Again, Isadore Braverman, the prosecution’s key witness, was absent. The defence Lawyer, Mr. Ring, applied for a discharge. The application was refused, and Darling was remanded for a further week.

The continued absence of Isadore Braverman from Victoria meant that when on David Darling’s next appearance at court on 6 October, he was ‘liberated on his own recognizance in the sum of £10 to appear and answer the charge wherever required to do so.’ So far, two men had been brought to court in connection with the deaths of the three men, but as yet nobody had been convicted.

The Weekly British Colonist, Tuesday, 7 October 1862

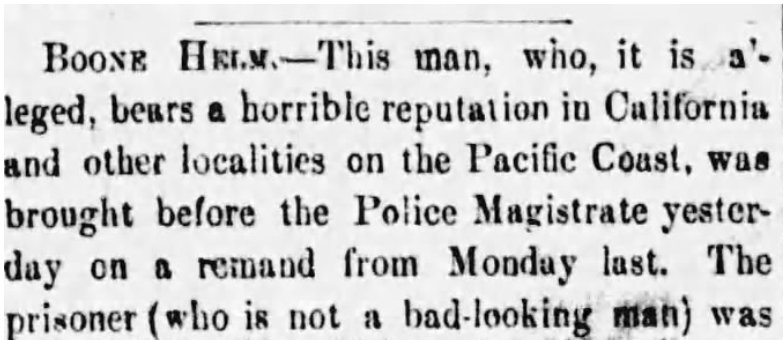

Boone Helm, arrested as a ‘suspicious character’ by Sergeant Blake of the Victoria Police, appeared in the Police Court on Monday, 13 October. Blake told the court that he had seen Helm walking the streets of Victoria on Saturday night.

Helm said that he crossed from British Columbia on the Enterprise steamer and that his friend had his blankets with him. Several people had informed Blake that Helm had stolen apples and taken drinks in bars without paying. Blake had also heard a rumour that the Kentuckian had killed a man in Salmon River, Idaho. No one came forward to prosecute Helm, so the magistrate remanded him in custody for three days.

Helm returned to the court the following Monday, 20 October. He was represented in court by Mr. Blake, the same man who had overseen the defence of David W. Darling. The Weekly British Colonist said of Helm: ‘bears a horrible reputation in California and other localities on the Pacific coast.’ The newspaper added that Helm ‘is not a bad-looking man.’

I am not aware whether Sergeant Blake of the Victoria Police was related to Mr. Blake, the defendant’s counsel. Counsel Blake alleged that there was such a prejudice against Helm that he could not receive a fair trial, adding that a subscription had been taking up to defray the cost of the prosecution. Those police officers who gave evidence denied the suggestion. Horace Smith, in turn, said that Boone Helm was known as a bad character.

The owner of the Adelphi Saloon testified that Helm had procured drinks there, when payment was asked for, Helm responded: ‘don’t you know that I’m a desperate character?’ It has always been asserted that the men who robbed and killed Sokolosky, Lewinand Beaucheir buried the gold dust with the plan to retrieve it at a later date.

Sergeant Blake added that those who knew Boone Helm the best were afraid of him. The magistrate delivered his verdict: he ordered Helm to find security to be of good behaviour for the term of six months, and he paid £50 and two securities of £20; if he defaulted, he would be jailed for one month. Helm defaulted and spent the next month repairing the streets of Victoria as part of a chain gang.

The Weekly British Colonist, Tuesday, 21 October 1862

In the spring of 1863, Boone Helm was captured at Fort Yale on the Fraser River. It is believed that Helm was making his way to the Forks of Quesnelle to retrieve the gold dust buried after Sokolosky and company were murdered the previous year.

He was taken to Victoria, where he was handed over to an American official who was taking him back across the border to face charges for the slaying on the Salmon River. Helm was transported to Port Townsend, Washington Territory. According to W.T. Collinson, he escaped from the jail.

Few people will be surprised to learn that Boone Helm did not live a long life. He died at the end of a rope in Virginia City, Montana, on 14 January 1864. Helm had joined up with the Henry Plumer ( or Plummer) gang. Plummer was a sheriff who allegedly led a cohort of men who robbed and killed with impunity in the Montana goldfields. Debate still goes on about how big a player Plumer was; whatever the truth of the matter is, a vigilance committee was formed, and Plumer and most of the men associated with him were hanged.

Boone Helm was hanged with six others. ‘Jack Gallagher protested his innocence; Sheriff Lane is said to have cried like a child, while Boone Helm denounced the committee in strong terms, and hurrahed for Jeff. Davis all the way to the scaffold.’

As was the case for Averena Rice, the Killers of David Sokolosky, Herman Lewin and Charles Beaucheir were never found accountable for the crimes that so shocked the Cariboo region in the summer of 1862.

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/walkem_george_anthony_13E.html

http://www.cariboogoldrush.com/barker/lorna.htm

https://www.quesnelobserver.com/columns/haphazard-history-towns-of-the-goldfields-7715347

https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/williams_creek.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Williams_Creek_(British_Columbia)

https://www.quesnelobserver.com/community/haphazard-history-gold-rush-women-7293401

https://www.newspapers.com/article/daily-evening-press-boone-helm-arrested/173699064/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-suspicious-c/173699177/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/daily-evening-press-dreadful-murder-and/173699372/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-horrible-mur/173758891/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-dutchy/173759059/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-david-w-dar/173759170/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-cariboo-inte/173759394/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/daily-evening-press-reward/173759554/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-darling-the/173902787/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-darlings-st/173902932/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-darlings-ca/173903024/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-liberated/173903121/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-remanded/173903207/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-the-late-mur/173903281/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-weekly-british-colonist-boone-helm/173903525/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-palmyra-spectator-boone-helm-hanged/174011455/

http://www.barkerville.com/vol10/boonehelm.html

https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/old/2.0/smith_h.html

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/cariboo-gold-rush

The Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography Vol. 2 by Don Thrapp.

Leave a comment