At the beginning of November 1755, four months after General Edward Braddock’s disastrous defeat on the Monongahela, Shawnee and Lenape (Delaware) warriors led by Shingas launched a series of devastating attacks on the Great Cove area of the Province of Pennsylvania.

On November 1, a party of about 100 Lenape and Shawnee warriors launched attacks on the Great Cove settlement. One of the Lenape chiefs leading the raiders was Tewea, known to the Anglophone settlers as Captain Jacobs. Arthur Buchanan, a Pennsylvania settler, had bestowed the English name on Tewea because he thought he looked like ‘a burly German in Cumberland County.’

William Fleming lived with his pregnant wife, Elizabeth, about seven miles from Great Cove. Fleming had been at Great Cove when Patrick Burns, a former captive who had escaped when sent to fetch water from a spring. Burns mounted a horse and returned to the settlements, spreading the word that the communities of Great Cove and its neighbour, the Conolloways, were in imminent danger.

Fleming told the Maryland Gazette that several of those alerted by Burns dismissed the warning ‘as only the groundless surmises of the timorous.’ Fleming wasn’t prepared to ‘be too fool hardy, but hasten home, and remove my wife and effects to a neighbouring fort.’

William mounted his horse and had travelled about five miles towards his home when two Indians emerged from behind a tree and took hold of his horse’s bridle. In good English, the two men instructed William to dismount his horse. They ‘shook hands and told me…I must go with them.’ The now-captive Fleming said that he stood before them trembling and speechless, ‘which my enemies, savage as they were, took notice of, and endeavoured to encourage me, by clapping me several times on the shoulder, and bidding me not to be afraid, for as I looked young and lusty, they would not hurt me, provided I was willing to go with them.’

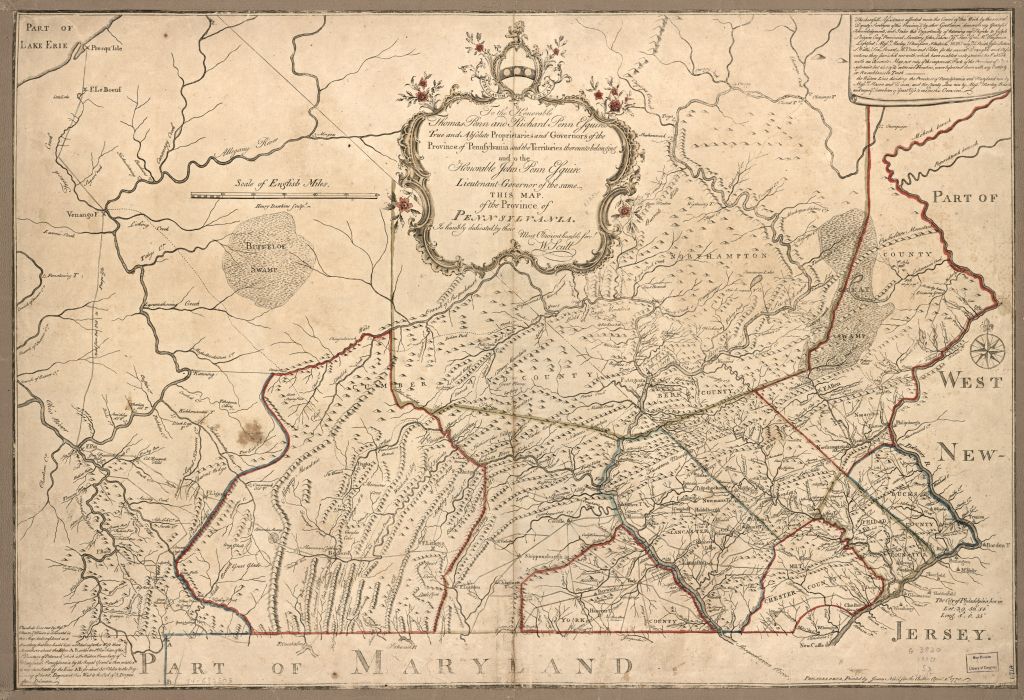

1770 map of the Province of Pennsylvania showing Great Cove and Little Cove at the map’s lower edge, just to the left of center.Public domain Wikimedia.

Fleming was taken to a ‘pretty well dressed’ Lenape who introduced himself as Captain Jacobs. Jacobs informed Fleming that he was leading the fifty Indians and promised that no harm would befall him if he would point out the houses ‘that were most defenceless.’ Fleming acquiesced to Captain Jacobs’ request, but after doing so, ‘I considered the dreadful consequences of my information, I was grieved beyond measure, and led the way more like a condemn’d criminal to meet his fate, than one that had a promise of life and happiness.’

A short time later, Fleming confessed to Captain Jacobs that he had a wife living a few miles away, ‘and that all my concern was for her.’ Jacobs was pleased with the news ‘for they wanted a woman to make bread for them.’ The raiders headed towards the Flemings’ home; Captain Jacobs had instructed his men to spare none of the settlers except young men and women.

Although he now believed that he and Elizabeth were not in imminent danger of being killed, being taken captive by Captain Jacobs’ force did not thrill William. The Hicks family lived near to the Flemings, and the route that William led his captors on took them to the Hicks’ homestead. William knew they had ‘a numerous family of able young men,’ whom William hoped would be able to rescue him.

The raiding party skirted the Hicks’ property, and stopped a short distance away to consider their plan of action. While William and his captors waited, two of the Hicks sons left the house, and headed towards a settlement they were working which lay close by.

’The Indians on seeing them ran behind trees, and ordered me to do the same between them.’ William obeyed the order and waited, hoping other family members would follow the brothers out of the house.

The two brothers advanced down the road towards where the Indians were hidden. The first of them passed the tree where William and one of the Indians were concealed. The warrior next to William leapt from his hiding place and quickly subdued the leading brother. ‘He screamed in a most piteous manner for help, but alas! There was none to be found. His brother fled back to the house with the utmost precipitation, whence not one would venture out. For my part (William’s), I was not in the condition to afford the least relief, not being allowed to carry even a stick about me.’

Captain Jacobs’ men quickly bundled their two captives away from the Hicks’ property, concerned lest ‘their new captive might be released by his relations.’

William stated that in contrast to himself, Hicks was proving to be difficult for the Indians to control; he refused to be silent; unaware of the the consequences his recalcitrance may provoke. William noted the ‘Resentment kindle’ in the faces of their captors.

The party travelled to within a mile of the Flemings’ home. One of the Indians ordered William to sit with his back against a tree ‘and after pulling my arms backwards round it, tied them with a deer’s sinew, then put on leather muffs on my hands to keep me from using my fingers, and then tied them likewise together.’ The Indians found great humour in ‘my timidity…made sport of my miseries and mock’d at my fears.’

William watched as a companion of Captain Jacobs, an Indian known to William as Jim, struck Hicks a blow with the back of his tomahawk. The initial strike stunned Hicks, but didn’t cause him to fall. Jim followed up with another smite of the tomahawk.

Hicks fell to the ground, and lay there motionless for a few minutes. ‘The inhuman wretch stood over him, in order to discover if any signs of life remain’d, and upon finding him stir, and put up his hand to his face to wipe of the blood which quite blinded him, took up the same tomahawk…and with one fatal blow sunk it in his skull.’

Hicks’ killer and his cohorts then recreated his slaying amongst themselves, according to William finding the episode highly amusing. One of the men scalped Hicks, and ‘all over besmeared me with his blood…and told me…nothing but my good behaviour…should save me from the same treatment.’

They untied William from the tree. His hands were ’so benum’d that I hardly expected to able to use them.’

Hauling William to his feet and pushing him before them, they advanced towards his home. William and his ‘guests’ arrived at his house a few minutes later. When Elizabeth saw her husband’s companions, she was horror-stricken.

While William consoled Elizabeth, Captain Jacobs’ force ran through the home, ‘ransacking the house from top to bottom, of every thing they thought worth taking.’

They then handed William ‘a sack of meal’ and Elizabeth was given ‘a bundle of cloaths.’ The couple were then marched from their home, unsure whether they would ever return.

After the raiders and captives left, Captain Jacobs. William said that he and Elizabeth didn’t bother to protest the Indians’ actions, as doing so ‘would have no more effect than speaking to the wind.’ Instead, they, ‘addressed ourselves to the Almighty for his protection, with a becoming resignation to whatever might be our fate.’

After leaving the Flemings’ burning house, the party headed through the woods for about half a mile when Jacobs ordered Jim and William to hunt for horses to carry plunder and for the pregnant Elizabeth to ride.

Unable to procure any mounts, the two men made their way to the Hicks’ property. Approaching the house, Jim kept William in front of him, protecting the Indian should anyone in the Hicks’ house should start shooting their guns at them.

Perceiving no threat, they reached the house’s door, and Jim entered, carrying his tomahawk in one hand and gun in the other. They found the house empty. After the murder of the captive Hicks boy the Family had fled to the sanctuary of a fort. William later found out that after leaving their home, the Hicks family had encountered another party of Indians; two members of the family were killed and the rest taken into captivity.

After discovering the family had fled, Jim ‘rumaged up such things as pleased him best.’ Jim carried his treasures a short distance from the home before returning and setting the building afire. He then instructed William to fling those things of most use to the homeowners into the flames before telling William to set the barn alight.

On returning and seeing that the barn had not been burned, Jim questioned why his instructions hadn’t been carried out. William answered that he’d ‘been fully employ’d in burning the other things.’ Jim grabbed a ‘brand of fire’ and set fire to the barn.

The two men gathered up Jim’s plunder and headed to where they had left Captain Jacobs and Elizabeth. They found the items taken from the Femings’ place but no sign of anybody. As William wondered what had become of his wife, Jim whistled, receiving one in return from Captain Jacobs ‘who had mov’d himself to some distance, for security.’

Jim praised William’s conduct in procuring plunder from the Hicks’ house and setting the barn ablaze. Captain Jacobs shook his hand and said: ‘Well done brother, you shall go to war with us to-morrow’.

After William was reunited with Elizabeth, she told him what had passed while they had been separated. Jacobs assured Elizabeth that no harm should befall her when she was with him. He threw her one of William’s shirts and ordered her to change into it, turning his back to her as she did. Then he took Jim’s bundle and sorted through it, taking what took his fancy, demanding Elizabeth not tell Jim what he had done. They then hid themselves away until Jim and William returned.

The party moved out and travelled until sunset, when they made a camp and lit a fire. Elizabeth, apparently becoming easier around her captors, asked Captain Jacobs ‘several questions touching their reasons for using the English as they did.’

The Indians answered that when General Edward Braddock assembled his force to march on Fort Duquesne, ‘he did not use them well, and had threatened to destroy all the Indians on the continent, after they had conquered the French.’ The French, stirring the pot, had informed the Indians that the ‘Pennsylvanians, Marylanders and Virginians had laid the same plot.’

Elizabeth then asked what would happen to the colonists captured by the Lenape and Shawnee attackers. Captain Jacobs answered, ‘ That they had been order’d by the French to bring them all to the Ohio. When you get there, you shall live well, and be given as kindred to our friends.’

Wiliam didn’t believe a word Jacobs had said. He had been told that the French were offering a bounty for the colonists’ scalps and prisoners if they ‘if they were young and fit for business’. Any elderly people and children captured ‘were kill’d and scalp’d, as well as such as were refractory and not willing to go with them.’

Elizabeth asked her captors whether they thought it was a sin to shed innocent blood. The Indians responded that the French had often assured them that it was no sin to kill ‘HERETICKS, and all the English were such.’

William reported that night after they camped, the Indians sat up ‘eating bread and cheese, and dry’d peaches.’ As well as ’smoaking tobacco.’ The tobacco they had obtained when Jim ransacked the Hicks’ place.

While the Indians were feasting, William heard a noise he couldn’t make out. One of the Indians told William that it was ’nothing but the spirit of that son of a whore (Hicks) whom we kill’d.’

Elizabeth asked if they were frightened by the presence of Hicks’ spirit. They answered that they were used to seeing spirits, both Indian and white, but these spirits could cause them no harm.

Finally, just before dawn, the Indians laid themselves down to sleep. Placing their firearms beneath them. As the Indians slept, Elizabeth started to plot the couple’s escape, whispering her plans to William. He silenced her, worried that the Indians were not truly sleeping.

The pair moved away from their captors, close to the fire, under the pretence of making the fire up and warming themselves. Elizabeth and William were not quiet about the fire: ‘we made so much bustle and noise, as we judged might awake persons in an ordinary sleep.’ The Indians, ‘still snoared on,’ so William divulged his plan to escape to Elizabeth.

‘I took up a tankard, and told my wife I would go towards a spring, at which I had been frequently before, and if after I got there they still slept on, desired she might follow: and added, if they should awake e’re we got off, our having the tankard might convince them we really wanted to quench our thirst.’

Looking nervously back towards the sleeping forms, Elizabeth swallowed hard and nodded her agreement. William was the first to leave the fire and head towards their agreed rendezvous point. William reached the spring and hunkered down to wait for Elizabeth to join him.

Waiting by the spring, William started to grow anxious when he finally saw Elizabeth make her way from the camp towards the spring. He decided to secrete himself in a thicket on the other side of the trail that led to the spring; he threw down the tankard, and ‘in my hurry, I ran against a sapling which stunn’d me, and I lay in this condition some time.’

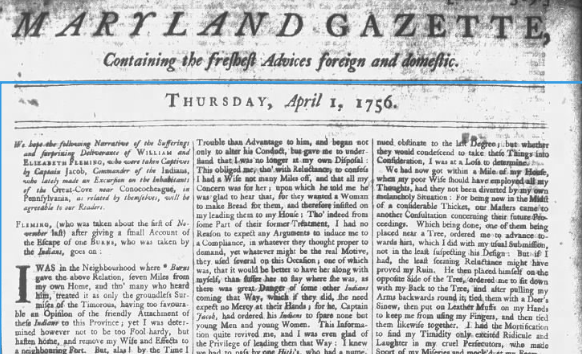

Elizabeth also gave an account of her capture by the Indians and subsequent adventures to the Maryland Gazette. Starting with what occurred after William had left her by the fire; ‘A few minutes after my husband was gone from the fire, finding the Indians took no notice of it, I concluded they were still asleep, and according to my promise followed him, but not finding him at the spring, knew not what course to steer.’

William Fleming’s story was featured in the Thursday April 1 issue of the Maryland Gazette. Elizabeth’s story was retold the following Thursday April 8.

Despite not knowing which way her husband had gone, she pushed on into the night’s darkness. Elizabeth ascended a hill from which she could see the fire and the sleeping forms of Jim and Captain Jacobs. She walked on until the morning came; she tripped over the corpse of a slain settler, ‘which I concluded to be Hicks, and therefore directed my course accordingly for our corn-field, near the remains of our house.’

Any relief Elizabeth felt at last knowing where she was quickly evaporated when she heard, ’ Two Indian Halloos, and the report of five guns.’ Believing herself in great danger, Elizabeth hid from sight ‘in some heaps of fodder.’ After lying hidden for some time, Elizabeth left her sanctuary towards a fort. Finding the fort deserted and ‘in great disorder,’ she once more moved on.

At one point, she climbed a hill to ascertain her whereabouts, ‘but when I began to look about, I saw so many houses in a blaze that I almost concluded the whole province was in flames.’

She walked down the hill until she reached a house almost completely consumed by fire. Near the house lay several dead cows, which Elizabeth presumed had been slain by the Indians. Fearing the Indians were still nearby, Elizabeth hurried away to find somewhere to secrete herself.

She found a cow which had been shot but was not dead, lying near a fence; Elizabeth managed to squeeze between the cow and the fence. She had only been there for a short time when she heard the sound of gunfire and found a new place to hide in a thicket.

She stayed in the thicket ‘till half an hour past sun-down, when hearing all quiet round me, removed to an oven belonging to Robert M’connel, and after some difficulty got into it, and rested about an hour; but being terrified with frightful thoughts and not being able to reconcile myself to it longer, left it.’

Elizabeth intended to climb another hill. She had almost reached the summit when she nearly stumbled upon a fire, ‘by the side of which lay two Indians, with white match-coats: the sight almost frighted me to death.’ She hid behind a tree, ‘where I stood trembling for near half an hour.’

She left the cover of the tree, but moving through shrubs and bushes, she made so much noise that she woke the Indians beside the fire. Once more, Elizabeth secreted herself behind a tree, feeling sure she would be spotted. To her amazement, the two Indians laughed and returned to their places beside the fire. Then Elizabeth ‘heard two or three hogs grunt and stir among the leaves.’ Elizabeth concluded that the hogs had roused the Indians from their slumber.

‘Being thus surprisingly saved, I tarried behind the tree till I judged the enemy had got to sleep, and then made the best of my way, blessing GOD for his remarkable deliverance, and wandered through the woods till day-break.’

As morning broke, Elizabeth spotted a mountain someway off in the distance. She believed that the mountain lay between Great Cove and Little Cove. She followed a ‘bad’ road, figuring it would lead her to the settlements. The mountain proved to be further away than she had anticipated when she had set out at the break of day.

On feet badly blistered, Elizabeth finally reached the mountain. Three hours after she reached the landmark, Elizabeth gained the summit, ‘when I found myself so much spent with fatigue and want of food, that I was obliged to throw myself flat on my face, and in that posture laid for near an hour.’

When she raised herself up, she discovered ‘some chestnut-husks’, but found that ‘squirrels or other vermin’ had devoured all the chestnuts, leaving Elizabeth with the empty husks and an empty stomach.

‘I then looked around me in order to discover some place that was inhabited, but the sky was so darkened with smoke, that I could only distinguish two houses in flames. It is impossible to describe the horror of my condition in this place…Every place I could lay my eyes on, seemed to be filled with desolation and ruin.’

A great feeling of despondency came over Elizabeth as she viewed the scene from the top of the mountain. ‘Having thus given vent to my grief , by tears and reflection,’ Elizabeth reported. She started back in the direction, ‘whence I came.’ She had only travelled about two miles before she was ‘overtaken by a horse, who came after me full-speed, with his bridle-head and a bell on.’ Elizabeth tried desperately to catch the horse, feeling she would have more chance of reaching the settlements on horseback. The horse ’soon made his way from me, and as I was not in a condition to follow him, was obliged to drop all thoughts of that nature.’

After the horse galloped away from Elizabeth, she was ‘alarmed by an Indian halloo.’ She presumed that whoever had owned the horse had fallen victim to the Indians. Elizabeth ‘hasted on with my crawling speed’ until she reached a ‘gum tree, into which I crept, tho’ with much difficulty.’

Elizabeth had barely found sanctuary within the tree when she saw two Indians pass close by. The two men were pursuing the horse and not looking about; fortunately for Elizabeth, ‘if they had, I should have unavoidably been discovered.’

Elizabeth put her good fortune down to providence and decided to stay in the tree ‘a considerable time,’ lest the Indians return. As she lay hidden, she heard the report of two muskets being fired, followed by ‘a terrible shriek.’

She decided to leave the gum tree and wandered for a mile through a ‘thicket’. At length, she came upon a path she followed for a mile and a half before realising she was going in the wrong direction.

Elizabeth rested for a while. She bound her blistered feet with cloth torn from the hem of her tattered petticoat. Returning the same way she had come, she reached a cornfield ‘where I found three ears of corn; I saw several stacks of fodder, but was afraid to take up my lodging in them, lest when the Indians came that way they might set fire to them.’

She collected three armfuls of the fodder, carried it ‘a good distance’ and laid it near a fence. She spent the next three days and nights there, rarely venturing far from it, as she ‘repeatedly heard the reports of guns and Indian Halloos.’

On her third night in her makeshift camp, Elizabeth heard a dog barking and the crow of a cockerel. The next morning, she set off in the direction she had heard the sounds coming from; she had only walked a short distance when she saw three trees that had only recently been set on fire.

Once more, Elizabeth found sanctuary by the fence and heard fresh gunfire in the distance. She waited about an hour; hearing nothing more, she walked towards a building that, at first, she believed to be a house, but as she drew closer, she saw that it was a stable. Elizabeth said that all the houses near the stable had been set ablaze. She was to learn later that the property had belonged to the Donaldson family.

In the area around the burnt-out dwellings, Elizabeth spotted ‘some fowls,’ she tried to catch them, but they eluded her. She then entered the Donaldsons’ garden, and ‘made a very plentiful meal of green keal and parsley,’ her first substantial meal for some time. She washed the greens down with ‘about three pints of water’ from a nearby spring.

She then crept into an ‘oven (which was left standing by the savages) and slept pretty soundly till midnight.’ The crowing of a cockerel woke her; she caught one of the birds near to the stable and dressed it. ‘But Alas! The very smell of the fowl so overcame me, that I was ready to faint several times ere it was ready; so I put it whole into my handkerchief.’

Elizabeth returned to the oven, and slept until morning had broken. She set out once more determined to find inhabited houses. She had travelled about half a mile from the Donaldson place, when, ‘I heard a man whistle, which at first I took to be a white man’s whistle, but upon listening more attentive, had reason to believe it an Indian Decoy.’

She raced back to her shelter; she had only been there briefly when she heard horses and the sound of white men conversing. She looked out, and saw a man ‘pass at some distance, I cried out to him for God’s sake to pity my distressed condition, and take me under his protection.’

The man raised his musket and levelled it at the ’strange figure…(being entirely in rags, and as black as any chimney-sweep.’ The man squeezed the trigger, fortunately for Elizabeth, the weapon misfired, otherwise ‘he would have certainly deprived me of that wretched life I had gone through so many difficulties to preserve.’

One of the man’s companions cried out: ‘Hold, hold, she is a white woman by her voice.’ There were ten men in total and they converged on Elizabeth. They told her they were part of a company of three hundred men.

One of the men, ‘Mr. Dickey,’ carried Elizabeth on the back of his mount, ‘tying me on with a belt (for I was so weak as not to be able to fit). Mr. Dickey carried Elizabeth about three miles to his home, where ‘I got refreshed with warm milk, and such things as I was able to take.’

The next morning she travelled with her new companions to ‘Adam M’connell’s plantation’ where: ‘what is my astonishment and joy when here my eyes are once more blessed with my husband!’

After he had recovered from being ’stunn’d’ by the sapling after leaving Captain Jacobs’ camp, William came across a property he knew: the residents had fled, so William continued to Conocheague.

On reaching the settlement, William learned that a company of three hundred men from Marsh Creek, under the command of Colonel Hamilton, ‘were out in quest of the enemy…I joined myself as soon as I could with these…intending to find…my wife, with whose condition I was now more affected, being out of danger myself.’

William’s company, as noted above, was at M’connell’s Plantation when the ten-man company rode in with to William’s delight and, ‘unspeakable surprize I found to be my wife.’

‘After greeting each other in the most affectionate manner, with tears of joy, we returned thanks to that indulgent being who led us safe through the wilderness, and preserved us from the jaws of death.’

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captain_Jacobs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Cove_massacre

The Maryland Gazette

Leave a comment