Edward Bonney, a 38-year-old alleged counterfeiter from Montrose, Iowa, arrived in Chicago on the steamship Champion early on Thursday, 25 September 1845. Bonney was accompanied by two other men, identified by the local newspaper, The Chicago Democrat, as ’two of the five murderers of Col. Davenport, Wm. F. Birch, alias Haines, and John Long, alias Howe.’

The Colonel Davenport named in the newspaper report was George Davenport, born in Lincolnshire, England, in 1783. A sexagenarian when he died, Davenport had lived an eventful life. He was a former sailor, fur trader, and Indian agent who had served in the 1st Regiment of the United States Army in the War of 1812, Fighting against the country of his birth. In the war, he served under the command of the notorious General James Wilkinson. Decades after Wilkinson died, Theodore Roosevelt believed that ‘in all our history, there is no more despicable character.’

After the war, he moved to the Rock Island area. In 1825, he was appointed the first Rock Island postmaster; he resigned the following year and became an agent for the American Fur Company (AFC), owned by America’s first multi-millionaire, John Jacob Astor. Davenport oversaw the AFC’s interests from Iowa to the Turkey River.

During the Black Hawk War of 1832, Davenport was commissioned a colonel by the Iowa Territory Governor John Reynolds and held the position of assistant quartermaster.

After the conclusion of the Black Hawk War, Davenport built a new home on Rock Island. Davenport and a group of partners purchased a large tract of land along the Mississippi River opposite the island. On this land, Davenport, Iowa, was founded on 23 February 1838.

Davenport succeeded Joseph M. Street as Indian agent for the Sauk and Fox tribes from 1838 to 1840. Two years later, he and several others concluded a treaty between the Sauk and Fox and Iowa Governor John Chambers for the sale of the tribes’ land in the territory.

After negotiating the treaty, Davenport, who had married Margaret Bowling Lewis, a widow 14 years his senior, in 1814, retired to a private life on his Rock Island estate. Davenport had several children, although it appears that all of them were illegitimate. His stepdaughter, Susan Lewis, gave birth to his first two sons, George L’Oste and Bailey, in 1817 and 1824, respectively. Catherine Pouitt, a laundress, bore him a daughter, Elizabeth, in 1835 at Rock Island.

On 4 July 1845, Geoge Davenport was unwell and alone in his Rock Island home while his family was at a ‘Sunday School celebration.’ Five men entered the Davenport residence. The gang of home invaders accosted the colonel and then shot him in the thigh.

The gang then dragged the wounded colonel through the house until he revealed where he had concealed his money. The robbers tied the mortally wounded Davenport in a chair and absconded with his watch, a gold piece, a chain, and ‘$600 in Missouri paper.’ Davenport clung on to life until evening; he died ‘having given full particulars of the robbery and murder.’

Before he died, Davenport identified one of his assailants as a man known as ‘Budd’. Budd was Robert Henry ‘Three-Fingered’ Birch, aged around 18; he was born in either New York or North Carolina. He moved to Illinois with his father and two brothers as a child.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Tuesday, 15 July 1845

The attack on Davenport was not Birch’s first crime; Edward Bonney alleged that Birch had been ’suspected of robbery and even of murder since he had attained the age of fifteen.’ Birch, a Mormon, was a member of the so-called Banditti of the Prairie, a gang of outlaws who plagued Illinois, Iowa, Indiana and Ohio.

The Banditti were similar to the Wild Bunch of nearly a half-century later. It is unknown how many members were in the gang; not every member participated in every crime. They were formed soon after the end of the Black Hawk War, and the murder of George Davenport occurred in the twilight of their reign.

John Baxter was one of the men who had gained entrance to the colonel’s home. Baxter was a family friend of Davenport’s and had visited the house before. Baxter had never been in trouble with the law before. The Weekly Plain Dealer newspaper described Baxter as ‘a sort of a spy and secreter for knaves of all kind without ever directly taking a part with them.’ It added that Baxter had lived at Rock Island for several years and ‘took tea’ with Davenport the week before he was murdered.

After the murder, the gang members fled to the upper Missouri, where they stayed at a tavern belonging to a man named Thomas Aitken (or Aikin). Aitken received a letter stating that the killers of Davenport were being pursued, and if Aitken provided them with sanctuary, he would be ‘lynched.’

It is uncertain how long after the murder of Davenport that Edward Bonney started to track down his killers. Bonney, who had many different trades in life, including miller, hotel keeper and city planner, tracked some suspects to Lower Sandusky, Ohio.

Towards the end of August 1845, a reward of $2500 had been offered for the capture of those guilty of the slaying of Col. Davenport. The Governor of Illinois donated $1000, while the dead man’s friends offered up $1500.

Having apprehended Birch( sometimes rendered in the press as Burch) and his accomplice, John Long. Bonney was transporting his charges across Lake Michigan when Birch stole Bonney’s travelling bag and pitched it over the vessel’s side into the lake. When Bonney arrested him, Birch had Davenport’s watch chain on him. Birch possibly threw Bonney’s portmanteau overboard, believing the chain was in the bag. Bonney had the sense to keep the watch chain and other evidence tying Birch to the murder in his pocket.

The Galena Advertiser noted in its 3 October edition that Dr. P.P. Gregg had returned to Galena the day before with John Baxter. Baxter ‘has for several years been a resident of Rock Island, and always bore a good name until his participation in this diabolical murder.’

Baxter had been captured at his brother-in-law’s property close to Madison, Wisconsin. The same edition revealed that William Fox(alias Sutton), ‘the dare-devil of the gang,’ had been caught in Indiana. The Advertiser asserted that there was little doubt that it had been Fox who had killed the colonel. The Indianapolis Courier reported that when Fox was captured at Cenreville, Indiana, he gave the names of two of his accomplices and where they could be found.

With Fox’s apprehension, all of the suspects were now in custody. William Fox was not detained for long, and he soon escaped custody. Aaron Long had been caught at a property about six miles from Galena.

Alexandria Gazette, Thursday, 16 October 1845

The St. Louis Reveille erroneously reported that two brothers (either Redman or Reding), charged by the authorities with Colonel Davenport’s murder, were hanged by a lynch mob. Like the rest of the men involved in the murder, the brothers were Mormons. They fled to Nauvoo, where they were given sanctuary.

On Monday, 6 October 1845, the Grand Jury of Rock Island County found a bill for murder against Robert Birch, William Fox, John Baxter, Granville Young and the Long brothers, John and Aaron. Fox, Birch and the Longs were charged as the principal actors in the slaying; Baxter and Young were accessories before the fact. The following day, all of the accused, except for John Baxter, argued for a change of venue. The judge refused their request.

Edward Bonney, the alleged counterfeiter-turned-private detective, making enquiries in the area, concluded that Granville Young had played some part in the murder of Davenport and befriended him.

Bonney took Young into his confidence and persuaded him that Bonney was part of the gang. He spoke to Young about robbery and counterfeiting and lent Granville a small sum.

Young had grown at ease in Bonney’s company and confided to him that Fox, Birch, Baxter and the Longs were the murderers, and they had revealed their plans to Young sometime before the murder was carried out.

Based on the evidence he had received from the unfortunate Granville Young, Bonney took measures to have the men Young named arrested. Birch, Baxter, Young and Aaron Long were quickly gathered up, and Bonney raced to Sandusky, where he found John Long and William Fox ‘betting on horse races and acting as fashionable gentlemen.’ Long was arrested, but Fox, as noted above, was held briefly before escaping from custody.

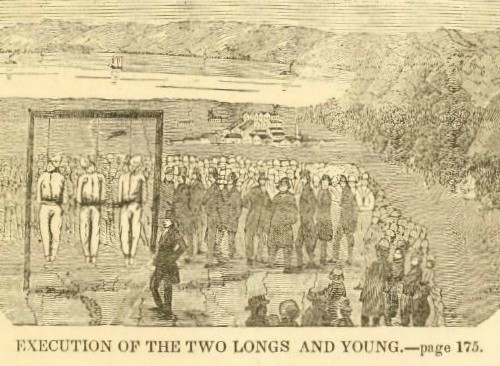

In October 1845, Granville Young, Aaron Long and his brother John were tried for the murder of George Davenport at Rock Island. Public sentiment was against the three defendants, and they were convicted and sentenced to be hanged at Rock Island on 29 October. It was widely expected that Granville Young’s death sentence would be commuted. It was a belief that would prove to be mistaken.

A spectator to the hanging was a journalist writing for the New York News. He noted that: ‘Although the morning was a rainy one, an immense concourse of people were seen assembling from every part of the country; and at the time of the execution I made an estimate, and should judge there were five thousand present; a promiscuous assemblage of men, women and children.’

At 11 o’clock, they formed a hollow square before the jail and marched the short distance to where the gallows had been erected; they were dismissed until after dinner.

The 130-man strong guard assembled on Elk Street near the jail at 12.30 pm, under the command of Captain Belcher. A half-hour later, The Green Mountain Boys, a band of musicians, took their position at the head of the square.

The door to the jail swung open, and the Rock Island sheriff Lemuel Andrews emerged with John Long, ‘dressed in a blue dress coat and pantaloons, light summer vest, thin boots, black cravat, and black hat. His dress and person were exceedingly neat and trim, and he surveyed the crowd with as much nonchalance, as if he were commander.’

B.J. Cobb, Lemuel Andrews’ deputy, led Aaron Long out. Aaron was ‘plainly dressed, but was neat and clean, and in tears, with his eyes on the ground most of the time.’

Granville Young left the jail accompanied by ‘Jacob Starr, Esq, the coroner.’ Young, dressed as smartly as John Long, in a ‘bottle green frock coat, blue pants, thin shoes, and a straw hat,’ was taking his date with the hangman as badly as Aaron Long. ‘His manner was that of extreme distress, and he seemed to be in great mental agony throughout. He wept constantly.’

The condemned men were followed from the jail by the Reverend Mr. Haney, a Methodist preacher, Reverend Doctor Gatchell of the Campbellite Church, and Elder Byron, a Baptist minister.

As the prisoners and their escort moved up Elk Street, past the courthouse, along Illinois Street, to where the gallows awaited them on Deer Street, they were accompanied by a ‘mournful slow and solemn dirge, composed for the occasion by Geo. P. Abell,’ and performed by the Green Mountain Boys.

The gallows were built on low ground with rising banks on each side, providing ‘a fair view for 20,000 people.’ The staging stood around ten feet from the ground and was large enough to accommodate 20 people.

The three prisoners climbed the steps to the staging and took seats next to Sheriff Andrews, Deputy Cobb, and Coroner Starr. Two members of their defence team, Mr. Cornwall and Mr. Guyer, were already seated on the staging. Two members of the jury that had convicted the three men, the Rev. Hitchcock and William Dickson, were on the stand.

‘All having become orderly, the band played another funeral piece of music, when the Sheriff stepped forward and read the writ of execution embracing the sentence of death!’

The condemned men were then allowed to address the great throng gathered to watch their last moments. ‘John Long stepped forward with the confidence of an orator and the air of a hero.’ He addressed the crowd, ‘With the most complete self possession.’

John Long asserted that he had not been fairly tried; he praised his defence team, ‘although they were assigned as counsel, that they had discharged their duty as men.’ He said that until 1840, he had lived an honest life before turning to counterfeiting and then robbery, ‘and presumed there were some in the crowd that he had robbed.’

John Long told the crowd that he was guilty and deserved death but that both his brother and Granville Young were innocent. He added that he would speak further after the other two men had spoken.

Sheriff Andrews introduced Aaron Long. He denied that he was guilty of Davenport’s murder. Telling the crowd he was ‘down the river’ when it took place. Aaron had little else to say and ‘returned weeping to his seat.’

Granville Young, with ‘hair as black as the raven’s wing’, was the last of the condemned to speak. ‘The great effort with him seemed to be, to create sympathy and excise the people to attempt a rescue.’ He excoriated Edward Bonney as a ‘counterfeiter and a horse thief.’ He said that the first counterfeit money he had ever offered had been obtained by Bonney.

Young left the stand in paroxysms of grief, and John Long returned to put the metaphorical boot into Edward Bonney, alleging that he had been involved in at least three murders as well as horse stealing and the counterfeiting of which Young had already accused him.

He urged the crowd to rescue the other two men. He finished his speech by thanking his defence team ‘and declared that the jailer and his wife had treated them with kindness…he made a graceful bow and retired.’

The Green Mountain Boys struck up another air, ‘Pleyel’s Hymn, which they executed in a masterful manner; during its performance, Young and Aaron Long wept like children.’ The band’s rendition of Pleyel’s Hymn brought tears to many attendees’ eyes. ’The sentiments which the piece created in our mind, were scenes of woe…the chambers of death, mourning…the coffin, mourning friends and heart-broken relatives…and a dark and lonesome passage to eternity.’

After John Long had returned to his seat, Reverend Gatchell read the Throne of Grace. Then, Reverend Haney read ‘appropriate selections of scripture.’ John Long got to his feet and shook hands with the clergy, Sheriff Andrews and his colleagues, as well as with Cornwall and Guyer and others gathered about the stage.

Both beset by tears, Aaron Long and Granville Young, followed their more stoic companion. The three men embraced, and John said clearly, ‘My companions in death, but not in crime.’

Sheriff Andrews and his assistants then adjusted the prisoners’ arms, placed caps on their heads and put the ropes around their necks. John Long lifted his cap and adjusted his rope, ‘remarking to the Sheriff that he did not wish to be choked before he was hung.’

At 3.30 pm, about two and a half hours after the spectacle had begun, ’The drop fell, and all supposed they were launched into eternity!’ As Granville Young and John Long dangled on the end of their ropes, Aaron Long’s rope broke, and he crashed to the ground beneath the scaffold.

B.J. Cobb and some others grabbed Aaron even as a section of the crowd shouted for the prisoner to be reprieved. While Cobb and his cohort returned Aaron to the stage, Coroner Starr had ascended the upper beam and was busy adjusting the rope.

As the rope was placed for a second time around Aaron’s neck, ‘Elder Byron, in his rapid and pointed manner, directed Aaron’s attention to his brother, and told him he was in eternity.’ Aaron replied, ‘and there is my companion too.’

Byron then told Aaron that if he was guilty, he should confess and make peace with God. Aaron answered that he knew of the robbery but was ignorant of Col. Davenport’s murder.

The second time the drop was sprung, Aaron hung suspended on the rope like John; he worked his hands for a little while. Granville Young, in contrast, struggled little. The three ‘companions in death’ were left to hang for about half an hour; they were then cut down and handed over to a team of physicians.

The newspapers lamented that ‘A great many women…were present’ at the hanging. ‘It is surpassing strange, how much of curiosity there is in mankind. And it is not singular that women should have their portion of it, and desired to have it gratified.’

Granville Young was buried locally, but the site of his grave is unknown. The Long brothers had further adventures after they were hanged. Aaron’s corpse was shipped to Dr. P.P. Gregg at St. Louis for ‘scientific study’; as will be recalled, Dr. Gregg was the man who arrived at Galena with John Baxter in tow.

To preserve it, Aaron Long’s body was enclosed in a barrel of rum. The boatmen conveying the cargo, ‘either ignorant or heedless of the special contents of the keg, drained off and consumed the rum during the trip, and the doctor received only the body and the dry keg.’

John Long’s skeleton was on display in a glass-fronted case at the Rock Island Arsenal; it then spent the next twenty years at the Rock Island Courthouse, near where he was hanged. The corpse was passed on to the Hauberg Museum at the Black Hawk State Historic Site.

John Long was finally laid to rest at the Pioneer Cemetery in the Black Hawk State Park, Rock Island, in 1978, a mere 133 years after his execution.

On 22 March 1847, Robert Birch broke out of the Knoxville, Illinois jail. He fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War, dying in Arizona Territory in 1866.

John Baxter’s trial for ‘aiding in the murder of Co. Davenport, at Rock Island,’ started on Friday, 13 November 1846. He was ultimately found guilty and was sentenced to be hanged. This was the second time Baxter was sentenced to death.

The previous February, the Supreme Court of Illinois reversed the sentence of death that had been imposed on Baxter by the Circuit Court; at that time, he was in jail at Rock Island. I was unable to ascertain Baxter’s ultimate fate.

In 1850, Edward Bonney published The Banditti of the Prairies or, the Murderer’s Doom! A Tale of the Mississippi. The book details his pursuit of Colonel Davenport’s killers and ran through six editions before 1858. The book is remarkably accurate when compared with contemporaneous records. Bonney died in Chicago on 4 February 1864, aged 56.

© Mark Young 2025

Sources

Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography A-F and P-Z by Dan L. Thrapp

St. Louis Reporter

The Ottawa Free Trader (Illinois)

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Portland Press Herald (Maine)

The Burlington Hawk-Eye

Wheeling Times and Advertiser (W. Virginia)

The Semi-Weekly Advocate (Belleville, Illinois)

Iowa State Gazette

The Monmouth Atlas

The Muscatine Journal

Baltimore Daily Commercial

Detroit Free Press

Vicksburg Daily Whig

Michigan Expositor

The Sandusky Clarion

The Louisville Daily Courier

Alexandria Gazette

New York Daily Herald

The Times-Picayune

The Telegraph-Courier

Franklin Repository and Chambersburg Whig

Daily National Pilot

Baton-Rouge Gazette

Weekly Plain Dealer

Mineral Point Democrat

St. Louis New Era

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Bonney

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_H._Birch

Leave a comment