The steamer Emily Harris arrived in Victoria Harbour from Nanaimo on the morning of Thursday, May 12, 1864. Among the passengers on board the vessel were three men—Edwin Mosely, Peter Petersen and Philip Buckley, the only survivors from a party of seventeen men employed in building a road from Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria and the Cariboo goldfields.

Englishman Alfred Waddington arrived on Vancouver Island in 1858, just after the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush had begun. Waddington was uninterested in joining the scramble for riches in the interior of British Columbia, preferring instead to promote settlement to the colony.

Alfred Waddington was elected to the House of Assembly in 1860. He served for one year, resigning in 1861. The following year, he helped compile the charter for Victoria. On 25 May 1868, Victoria became the capital of British Columbia.

At Noon on Saturday, 16 August 1862, Mr. C.B Young, the sheriff of Victoria, ‘announced to the habitants round-about the Hustings, that he was prepared to proceed with the nomination of Mayor and Councillors for the first Municipal Council of the City of Victoria.’

The sheriff then nominated Alfred Waddington ‘as a fit and proper person to fill the important position of Mayor.’ Sheriff Young added that Waddington was ‘a man of talent and ability, and had always taken the most prominent part in every public movement that had taken place in Victoria.’

Dr. James Trimble, who would serve as Mayor of the city from 1867 to 1870, then put forward Thomas Harris as his nominee ‘and decanted warmly on that gentleman’s qualifications.’

No other candidates were put forward for the position. Sheriff Young ‘called for a show of hands, when but four of five were held up for Mr.Waddington, and the remainder for Mr. Harris…the Sheriff declared Mr. Thos. Harris duly elected Mayor of Victoria—a decision that was received with the most vociferous cheering.’

There were more cheers and applause when Harris made a speech in which he thanked those who had voted for him from the ‘bottom of his heart.’ Adding ‘that he was unable to thank them as they deserved.’ Thomas Harris would serve as mayor till 1865, when Lumley Franklin replaced him.

After the vote for mayor was completed, Sheriff Young announced that nominations for positions on the municipal council could now be received. The Sheriff handed proceedings over to Mr. Edward Green, who made a lengthy speech to the assembled crowd before the nominees were chosen and then grilled by the citizenry. The election for members of the council was set for the following Monday.

Even before his defeat in the mayoral election, Waddington had been lobbying his political allies and members of the press for support in his bid to construct a wagon road that was planned to run from Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria, where it would meet up with the Cariboo Road (also, the Cariboo Wagon Road, The Great North Road, and the Queen’s Highway), and on to Barkerville, located on the western side of the Cariboo Mountains.

Alfred Waddington

Barkerville had been founded earlier in 1862 and was named after Billy Barker, a 45-year-old native of Cambridgeshire. Barker and his companions had struck it rich in an area known as Stout’s Gulch. After only a short time of prospecting, Barker and his crew pulled out about 60 ounces of gold at a depth of around 52 feet below ground.

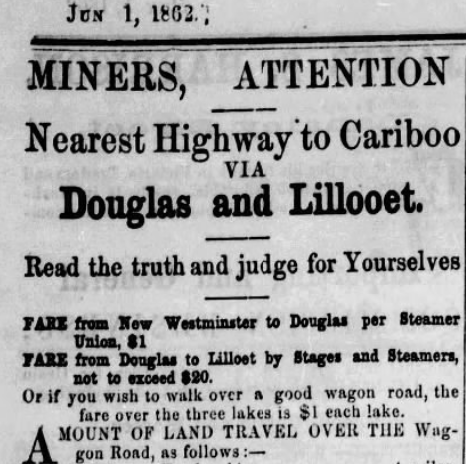

At the same time that Waddington proposed the Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria wagon road, regional newspapers promoted other routes. One such route, the Douglas Road, was ‘constructed by Messrs. G.B Wright &co.’

‘Miners, Attention!’ Read the advert’s headline. It informed the reader that it was the nearest highway to the Cariboo Goldfields via Douglas and Lillooet. Adding: ‘Read the truth and judge for yourselves.’ The advert claimed that a ticket on the steamer Union from New Westminster to Douglas was $1, and the fare from Douglas to Lillooet ‘by stages and steamers not to exceed $20.’

Daily Evening Press Sunday 1 June, 1862

For any gold seeker who wished to walk on ‘a good wagon road,’ the cost of crossing the three lakes, Lillooet, Anderson, and Seaton lakes, was also just $1 each.

The distance from Douglas to Lillooet was 55 ½ miles. The settlement known as Douglas was Port Douglas; it was sited east of the mouth of the Lillooet River and at the head of Harrison Lake.

Laid out in 1858 during the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, Port Douglas was named for James Douglas (he was knighted in 1863), the first Governor of the Colony of British Columbia. Port Douglas was the second major settlement on the mainland of the colony after Yale, which lay to the southeast.

After leaving Lillooet, the treasure-seekers would travel to Quesnelle City, the present-day city of Quesnel, which lay 172 miles away. Quesnelle City was named for Jules-Maurice Quesnel, who accompanied Simon Fraser on his quest to the Pacific Ocean in 1808.

The route from Lillooet to Quesnelle City would take the Argonauts via Canoe Creek, Dog Creek, Alkali and Williams’ Lake. The advert advised travellers for the Cariboo Goldfields that ‘good houses will be found at all the points named where feed for man and beast can be obtained.’ It was noted that there were thirteen hotels between Port Douglas and Lillooet, while the alternate route between Yale and Lytton was not only longer but had only three hotels on it.

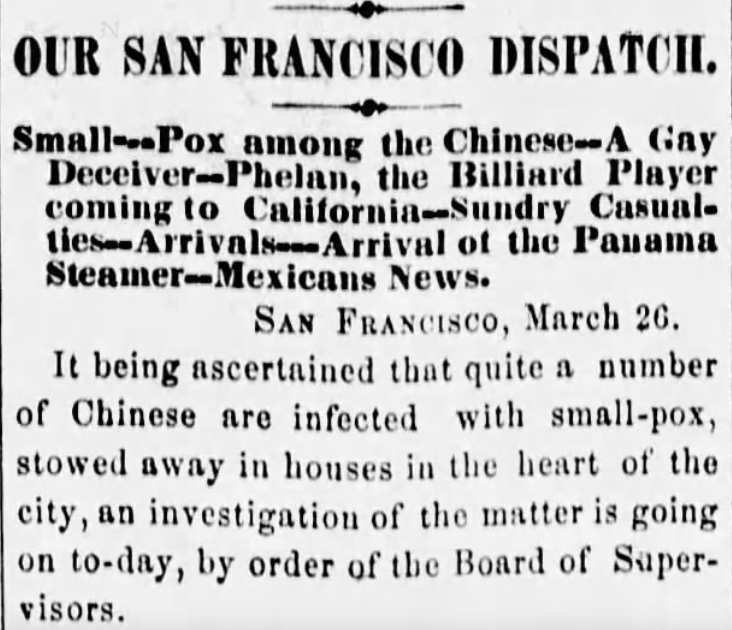

Around the same time the Douglas Road was advertised, smallpox arrived in the colony.

On the afternoon of 12 March 1862, the vessel Brother Jonathan, commanded by Captain Samuel DeWolf, steamed into Esquimalt, just outside Victoria. She had disembarked from San Francisco three days before, carrying 350 passengers, 101 of whom were destined for Vancouver Island. Most passengers left the ship at Portland, Oregon, and headed for Idaho’s Salmon River Gold Rush.

Victoria’s Daily Evening Press informed its readership that in addition to the passengers, the Brother Jonathan carried ‘a cargo of assorted merchandise, and 21 mules. The cargo and mules are valued at $26,000. A very small letter mail arrived by this vessel, and only one dozen newspapers.’

The Brother Jonathan was scheduled to leave Esquimalt for San Francisco via Portland at 4 o’clock the following afternoon. A cabin between Victoria and San Francisco cost $50; a berth in steerage would cost a passenger $25. A cabin between Victoria and Portland was $20, with the traveller spending $10 for steerage.

The Weekly British Colonist reported that when the vessel left on its return to California, ‘Her decks were alive with people…she carried down 400 passengers. No treasure, except a small amount in private hands, was shipped.’

On 18 March, Victoria’s newspapers reported that one of the passengers who had disembarked from the Brother Jonathan had the smallpox virus. The following week, another steamer from San Francisco brought a passenger infected with variola.

The Marysville Appeal reported that ‘quite a number of Chinese (in SanFrancisco)are infected with small-pox.’ A few days later, The Sacramento Bee stated that the Grand Jury of San Francisco had issued its final report on the smallpox outbreak. The document was published on Saturday, 29 March; it said that: ‘They find the small-pox hospital has been so crowded as to render it unsafe and unfit place for persons afflicted with that disease; they recommend that the building be enlarged and so arranged that those patients may have separate rooms, who wish to have personal nurses.’

The Marysville Appeal 27 March 1862

Even before the Brother Jonathan had disembarked the passenger with smallpox at Esquimalt, it was reported at Hope in the Cariboo that the smallpox had broken out among the First Nations at Boston Bar and that ‘many had died.’

On 1 April, Victoria’s Daily Evening Press conveyed to its readers the news of ‘An Indian woman who resides near Mr. Gerritsen’s bakery…has been stricken down with small-pox…this poor woman should be removed as speedily as possible.’

James Douglas summoned ‘all the principal Indians of the various tribes now living here’ to a meeting at the police office. About thirty First Nations agreed to be vaccinated, including ‘King Freezy (Cheealthluc), his queen and the young Princess.’ The doctor carrying out the vaccinations was Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken. It was reported that the Indigenous were at first reluctant to be vaccinated but were persuaded that ‘the small-pox was far worse than their enemy, the measles.’

By the end of April, Dr. Helmcken had vaccinated more than five hundred local First Nations people. It is believed that the Songhees, who neighboured Victoria, received the bulk of Dr. Helmcken’s attention.

When news of a further outbreak at an encampment on Vancouver Island reached them, the Songhees departed for an island in the Haro Strait. Due to the vaccinations and their self-imposed quarantine on the island, few Songhees perished.

In an address to the assembly, Governor Douglas proposed building a smallpox hospital in an isolated location; Dr. Helmcken and other members of the assembly objected to the cost.

Helmcken, also the Speaker of the Assembly, opposed a fully staffed hospital and did not wish to force all patients to go there, adding that it would interfere with their liberty. Helmcken accused Douglas, who had witnessed two earlier smallpox outbreaks on Vancouver Island, of being alarmist.

The Tuesday, 29 April, issue of the Weekly British Colonist carried news from Reverend A.C. Garrett that the smallpox was decimating the Tsimshian people (meaning ‘Inside the Skeena River’). ‘Twenty have died within the past few days; four died yesterday, and one body lies unburied on the beach, having no friends, and the others are afraid to touch it.’

Garrett added that the dead were buried under a few inches of earth, and the prevailing fear was that ‘nearly the whole tribe will be swept away.’

A rumour published on the same page said a white man arrived by canoe and encamped near the Tsimshian First Nations reservation. ‘During the afternoon he invited a Chimsean Indian and his wife to his tent and gave them a pailful of molasses and some biscuits, which they carried home, partook of themselves and gave to their family and friends.’

It was reported that all who ate the food became violently ill during the night ‘and before morning four of them had died.’The rest of the afflicted recovered ‘after suffering excruciating agony for many hours.’

At the beginning of June, an encampment of Haida was sited at Ogden Point, where the cruise ship dock is today. On Thursday, 5 June, Superintendent Horace Smith and Officer Weihe set out for Ogden Point to instruct the Haida to depart to the north; their homeland was traditionally Haida Gwaii (then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands).

As the two officials approached Ogden Point, they ‘were surprised to find a death-like stillness reigning over the neighborhood and a strong smell of decaying animal matter.’

Smith and Weihe approached the camp cautiously; they discovered several bodies ‘lying around corrupting and tainting the air with their foul exudations.’ Just two weeks previously, there had been around 100 Haida in the area; now, the two men could find no living soul.

Houses were left abandoned with their doors open; possessions were strewn on the ground—weapons, clothes, children’s toys ‘lay scattered confusedly on the floors or on the ground hard by.’

Smith and Weihe searched the area fruitlessly until a man from another tribe approached them. He informed the officers that ‘all but 10 or 12 of the Hydahs had fallen victims to the ravages of the destroying disease.’ The man added that on the previous Wednesday, the surviving Haidas had procured ‘a canoe, put into it such…as could be accommodated, and started for the north, leaving several bodies unburied, but humanely taking all their sick with them.’

The two police officers then checked inside the lodges; under the floors of each of the dwellings, covered with a few inches of dirt, lay the victims of the smallpox. The newspapers reported that under each lodge lay at least one corpse, sometimes as many as five—men, women and children.

Smith and Weihe set fire to the lodges. The Weekly British Colonist remarked that the flames destroyed ‘the bark tenements and the sad remains of poor humanity which they contained. After the fire had done its work,quick-lime was thrown thickly over the site of the encampment, and the officers returned to town.’

Reports from Fort Alexandria spoke of hardship on the trail: four gold seekers who were part of a larger group had contracted smallpox and had been ‘left among the Chillicoaten (Tsilhqot’in) Indians’, the report added that the men were ‘doubtless dead’.

For those men who reached the Cariboo, riches were to be had; a group known as The California Company had struck it rich. On Van Winkle Creek, Chisholm Creek and Davi’s Creek, ‘Moderate wages are made by about a dozen men on each creek.’ Sugar Creek was described as ‘a humbug’ while Antler Flat, and especially Last Chance, proved productive.

Mules proved prohibitively expensive; at Quesnelle, they were selling for up to $275, while horses could cost $100.

There was crime, too. E.T. Huston, who had owned a clothing store on Government Street in Victoria and later a similar establishment in New Westminster, had been stabbed by an assailant described simply as ‘a German’ on Lightning Creek. ‘The German is in custody. Huston is still alive.’

As well as the stabbing of Huston, there were cases of robbery on the Douglas Portage reported in the Victoria newspapers. The Daily Evening Press conveyed the news that theft from wagons during the night was so common that ‘proprietors have been compelled to set a watch for the thieves. The Abstraction of goods…was generally effected during the night time at the stopping places.’

Three men had been caught while committing the robberies. Two had been transported to New Westminster on the steamer The Governor Douglas and were scheduled to be tried at the next Assizes.

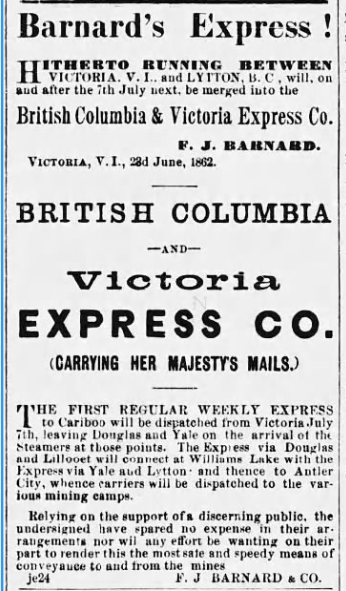

Francis Jones Barnard, a native of Quebec, arrived in Fort Yale in 1859. Eschewing the Overland Route, Barnard had left Toronto the year before, travelling via New York and Panama. His efforts to strike it rich in the goldfields proved fruitless. He spent some time splitting cordwood and then served as a constable in the Cariboo.

By 1860, Barnard worked as a purser on the Fraser River Steamer Fort Yale. The ship’s engines blew up near Hope, and Barnard once more changed occupations. He helped construct a trail between Yale and Boston Bar.

In December 1861, Barnard purchased Jeffray and Company, the business that carried the official mail from Victoria to Yale. That winter, he undertook the 200-mile round trip on foot from Yale to New Westminster. The following spring, he conveyed the mail from Yale and the Cariboo, a 760-mile round trip; he charged two dollars a letter for this service.

When, in May 1862, Governor James Douglas called for tenders for delivering the mail between the two Cariboo settlements of Yale and Williams Creek, Barnard and his business partner Robert Thompson formed the British Columbia and Victoria Express Company.

Barnard and Smith submitted a successful bid of £1,555 for one year, and on 7 July, Barnard left Victoria with Her Majesty’s mail. During that first year of operation, F.J. Barnard trekked on foot between Yale and Williams Creek, trailing a pony which carried the mail behind him.

The Weekly British Colonist Tuesday, 24 June 1862

Alfred Waddington had spent the winter of 1861-1862 negotiating with James Douglas for the right to build a trail from Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria via the valley of the Homathko River. In March 1862, Waddington was granted a charter authorising him to build a trail over the proposed route. Almost immediately, Waddington obtained a further agreement authorising him to build a toll road instead of a trail. Waddington’s concession was to run for ten years.

Colonel Richard Moody of the Royal Engineers and Alfred Waddington signed the agreement. The road was to be completed within twelve months. The Tolls levied for travel on the planned road were: ‘one cent and a half per pound on goods; one dollar per head on beef cattle and pack animals, and fifty cents per head on sheep, goats and swine.’

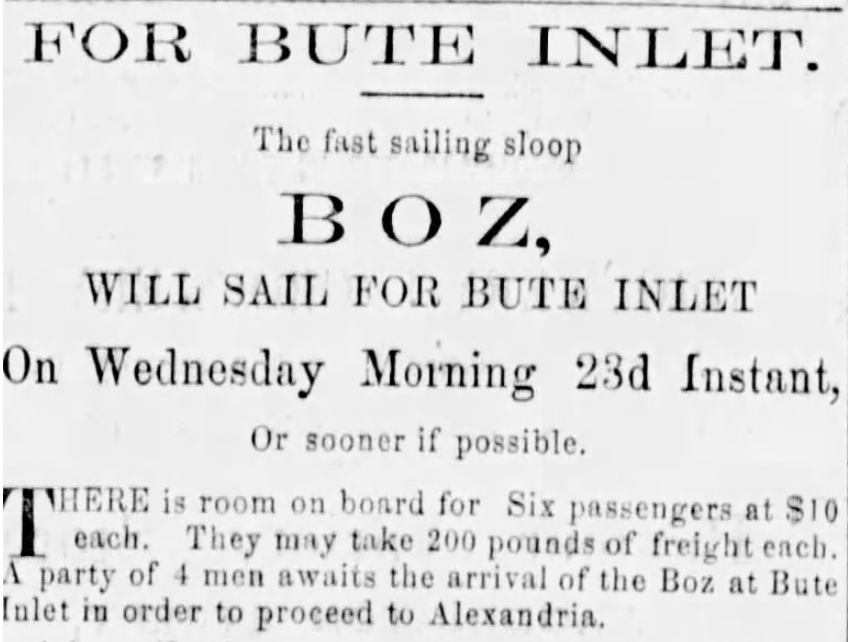

William Jeffray, the man from whom Barnard and Smith had bought the company that transported the mail from Victoria to Yale, was advertising ‘The fast sailing sloop Boz’ to transport gold seekers to Alexandria via Bute Inlet. The sloop could carry ten men; four had already signed up.

The cost of the voyage from Victoria to Bute Inlet was $10. Passengers were allowed 200 pounds of freight each. Once the Boz arrived at Bute Inlet, the passengers would embark 44 miles up the river in a ‘large Northern canoe.’ From there, they would be piloted the 150 miles to Alexandria. Any would-be Argonauts were assured that ’There will be no difficulty in obtaining Indians to pack at very low rates.’ Anyone reading the advert would have to act fast; the advert was posted in the Daily Evening Post on Sunday, 20 April, and the Boz was scheduled to sail for Bute Inlet ‘On Wednesday Morning 23d, instant, or sooner if possible.’

Daily Evening Press Sunday, 20 April 1862

A party of men named the Exploring Expedition left Victoria on 15 May. Hermann Tiedemann, a native of Berlin, led the expedition. He arrived on Vancouver Island in 1858 and became the colony’s first professional architect. In 1859, he received a commission to design the legislative buildings. The assembly was completed in 1864 and was used until 1898 when Francis Mawson Rattenbury’s replacement was completed.

On 3 March, Tiedemann resigned his post as principal draughtsman to the colonial Surveyor, Joseph Pemberton, to study the feasibility of building the road from Bute Inlet to Fort Alexandria.

Seven men accompanied Tiedemann, including ‘One of whom spoke Chilecoten.’ Enroute to Alexandria, they encountered a Mr. Anderson, who, when he reached Victoria, reported that one of the three ‘Indians’ journeying with Tiedemann abandoned the venture before they reached Bute Inlet, a second Indigenous man had baulked when he saw the ‘Swollen state of Bute River.’

Tiedemann and four companions were forced to tow a large Northern canoe up the Bute River. They had been expecting to find and hire guides along the route but met none. While fording a stream, Tiedemann was swept off his feet by the force of the water ‘and nearly lost’.

Tiedemann lost all of his instruments in his inadvertent dunking, and later, in another mishap, the party’s provisions were also lost. The men survived on fish and wild fruit traded from members of the First Nations they encountered in the interior.

The team constructed a raft when they reached Big Lake and crossed the water. They soon encountered a group of men from Bentinck Arm and continued together to Alexandria. Tiedemann reported that when the Exploring Expedition reached Alexandria, he was ‘reduced to a skeleton, unable to walk.’

In Victoria, Mr. Anderson relayed, ‘the party are all in good health.’ Tiedemann had informed Anderson that they had found ‘a fine natural pass through the cascades for a wagon road.’

The news that Tiedemann and his men returned to Victoria with was greeted with excitement in the pages of the newspapers. The Weekly British Colonist reckoned that the ‘complete verification of the line as projected by Mr. Waddington as pregnant with great advantages to this town. Victoria with Fraser River and Bute Inlet may thus command the entire trade of British Columbia.’

Towards the end of August, Alfred Waddington announced he and thirty workmen were preparing to leave for Bute Inlet. On Tuesday, 26 August, Waddington held a public meeting at the theatre in Victoria ‘for the purpose of making the public acquainted with the Bute Inlet Route, it will offer to the Cariboo miners, as well as to all merchants…interested in the prosperity of Victoria.’

Around 300 people attended the meeting, which started at eight o’clock. Alfred Waddington was introduced to the crowd and strode onto the stage to great applause. A map of the proposed route was displayed on the stage beside Waddington. The Englishman described vividly how he had been ‘laughed and sneered at’ when he first put forward his theory that there was a pass in the Cascade Mountains through which a wagon road to the mines could be laid.

Waddington lectured his audience on the Homathko River. Pointing to the map, he showed the country’s topography around the proposed route. Waddington claimed that travellers would only encounter two hills on the whole route, one 400 feet and the other 800 feet.

Where the Bute trail intersected the Bentinck Arm trail at Puntzi Lake and continued the 90 miles to Alexandria, the country was ‘more like our English parks than a wild stretch of land.’

Hermann Tiedemann had reported to Waddington that there was ‘rich agricultural land above Chilecooten, on an immense plain, only 2400 feet above the level of the sea.’ Furthermore, ‘Mr. Ogden, of Fort Alexandria,’ had informed Waddington that there was so little snowfall. ‘that Cayoosh ponies lived the whole winter without shelter.’

Waddington informed those gathered inside the theatre that an excellent harbour with good anchorage for large vessels could be found at the mouth of the Homathko River. Bute Inlet itself ‘was as straight as a chimney.’

Waddington claimed that the wagon road to a point above the Quesnelle River could be constructed for $220,000, ‘but a portion of the road—the most difficult portion…could be constructed for $50,000.’

He added that he planned to issue 500 shares for sale at $100 each to form a company to build the most challenging part of the road.Waddington then spoke further about the route, the cost of provisions available there and ‘the diggings’. Before surrendering the stage to his old friend C.B. Young, he said, ‘if the route was not opened, the people didn’t deserve to have any miners in the country next year.’ These sentiments brought further applause and stamping of feet from the enthused spectators.

C.B. Young then addressed the crowd, praising the Bute Inlet route while dismissing the Bentinck Arm route. Young subscribed ‘for several shares’ and urged those assembled to do likewise.

The Weekly British Colonist informed its readership that by Monday, 1 September, 125 shares in the Bute Inlet Road Company had been sold and added, ‘If such confidence continues, the proposed expedition will soon be able to start.’ And ‘It is much to be desired that this route should be opened so that returning miners may be able to pass over it before next winter.’

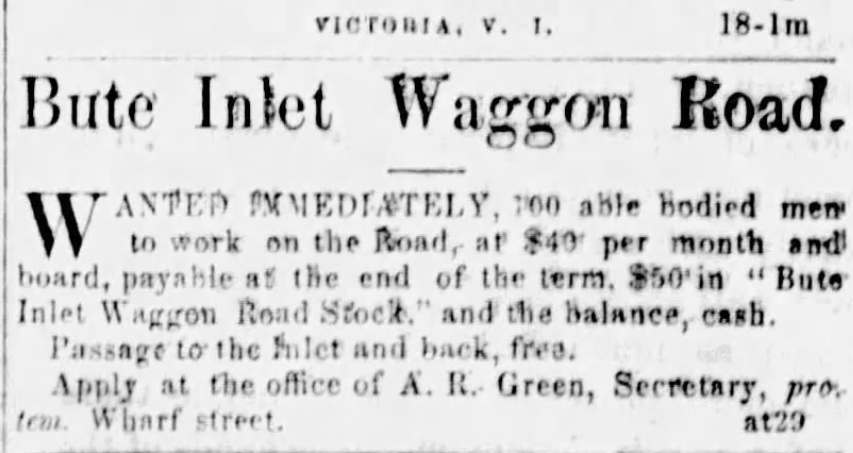

Before the end of the next week, adverts appeared in the local newspapers for ‘100 able bodied men to work on the Road.’ Wages would be $40 per month. ’$50 in “Bute Inlet Waggon Road Stock”, and the balance, cash.’ The wages would be paid at the ‘end of the term’.

Daily Evening Press Sunday, 7 September 1862

On Tuesday, 9 September 1862, at 6 am, the steamer Otter slipped out of Victoria Harbour and headed towards Bute Inlet with plans to ascend the Homathko River; on board the vessel was Alfred Waddington, C.B. Young and 90 passengers, intending ’to open the wagon-road.’ The party returned to Victoria aboard the same craft in the second week of November.

By May 1863, the Victoria newspapers were alive with reports of the vast sums the men in the diggings were extracting. Frank Fellows, who was at work on Williams’ Creek, arrived at Yale with the news that three men working on the same creek had earned $39,000 in one week.

Fellows estimated that one thousand people were working on Williams’ Creek, and the number was growing daily.

The steamer Governor Douglas arrived at Victoria from Yale via New Westminster on 11 May; on her decks, she carried twenty passengers transporting ‘upwards of $30,000 in gold dust.’

Also in May, rumours reached Vancouver Island of an attack on Waddington’s workforce constructing the wagon road. Richard Hardisty, the chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) Fort Simpson post, reported that ‘while at Nanaimo he heard Dr. Benson say that five men had been killed and he also heard it reported in Mr. Howe’s shop.’ Dr. Alfred Benson was a surgeon for the HBC.

Hardisty alleged that five members of Waddington’s party had been killed by the ‘Eucataws.’ This same group of men were reported to have slain Captain Freimuth ‘and his mate,’ of the schooner John Thorndyke a short time before. A reward of fifty blankets was offered for the apprehension of the murderers of the two sailors by Captain Moffitt of Fort Rupert at the north end of Vancouver Island.

The Victoria Daily Chronicle confirmed the news of the attack on Waddington’s men in their 19 May edition. It added that two other men had been killed, noting that ’No particulars were given, nor was anything said that would afford a clue to the particular tribe to which the attacking party belonged.’

In the same edition, the newspaper added: ’The late murders have greatly exasperated the settlers, and they openly threaten that if Government does not speedily avenge the deaths of the victims that they will…kill every Indian whom they may meet.’

While Waddington’s workforce was beset with problems, Wright’s Wagon Road running from Clinton to Alexandria was scheduled to be completed by 1 June ‘WHEN A Regular line of stages WILL RUN FROM DOUGLAS TO ALEXANDRIA.’ A regular stage would run between Port Douglas and Alexandria, where the steamer Enterprise would transport the gold seekers down the Quesnelle River to within fifty miles of Lightning and Vanwinkle Creeks. The journey to the Quesnelle would take five days.

Alfred Waddington returned to Victoria in a canoe from Bute Inlet on 29 October. With him were eighteen workmen; another twenty men were working on the wagon road, preparing to blast their way through 75 feet of rock, the last natural obstacle on the road to Alexandria.

Waddington had travelled seventy miles by horseback, almost to the mouth of the Quesnelle. He had surveyed the whole route and was satisfied that the road would be completed the following year. Those workers busy blasting through the canyon walls had constructed several large cabins where they would reside during the winter.

The sloop Random, commanded by Captain Dirk, arrived at Victoria on 2 January 1864; 15 men of Waddington’s force returned on the vessel, and the remainder of the men stayed behind to care for the mules ‘and carry on various improvements, so that everything may be ready for going through early in the spring.’

The men had blasted through the canyon, and although the ‘sun has not been visible since the 25th September,’ the weather was mild, ‘except upon three days, when the thermometer fell to 18 degrees below freezing point.’ In the canyon, there were eight inches of snow; at the head of Bute Inlet, snow was scarce and did not last long.

With Captain Howard at the helm, the Schooner F.P. Green delivered men and supplies to Bute Inlet in early April and reported, ‘not a day passed on which snow did not fall.’ Howard added that there was no news from the men working on the trail.

Also, in early April, A.F. Main, a Victoria-based real estate agent and auctioneer, advertised in the Daily Chronicle and other regional newspapers that he had ‘been instructed by the liquidator (D. Lenevue)…to sell by public auction…All the Right, Title and Interest of the Bute Inlet Waggon Road Company, Limited, consisting of Agreements for a charter for said Road, land the Rights ensuing therefrom, Work and Surveys done on the Road, and Claims against Defaulters.’

The sale was to commence at Noon on Thursday, 11 April, at Duncan & George’s salesroom on Government Street.

The Daily Chronicle reported that the sale had occurred on 14 April, and the Rights and Property had been sold ‘after some spirited bidding’ for ‘$14,000—a great bargain if the undertaking turns out successful.’

Any excitement felt after the sale soon dissipated when Alfred Waddington received a letter from the ‘Town site—Bute Inlet, May 4th, 1864.’ The missive penned by ‘A. Samper’ informed Waddington of the ‘sad affair that took place on the 30th of April.’

The body of Waddington’s men were divided into two groups led by Cornish-born foreman William Brewster was working on the Bute Inlet Road. Brewster and three colleagues were ahead, blazing a trail, while the bulk of the men were working in the area known as the Third Bluff.

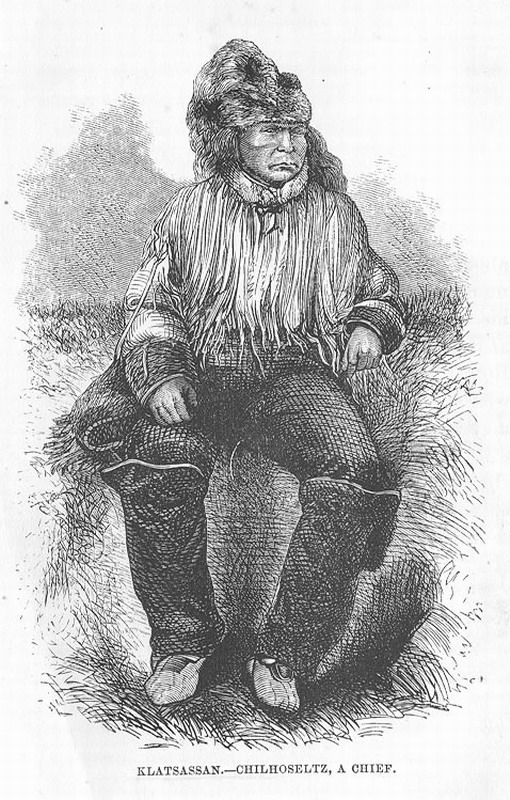

Timothy Smith, an Englishman employed by Waddington, was operating a ferry on the Homathko River, about nine miles from the Third Bluff. A party of Tsilhqot’in men led by their chief Klattasine (Lhatŝ’aŝʔin), the English rendering of Klattasine’s name was ‘Nobody Knows Him’ or ‘We Do Not Know His name’, reached the ferry on the Homathko River. The Tsilhqot’in men found Smith smoking a pipe in front of a fire.

Smith was shot through the head when he refused to give Klattasine and his followers anything. The Tsilhqot’in dragged Smith’s body to the river and threw him in. After disposing of Smith, the men burned the ferry and ransacked Smith’s cabin. The ferryman’s killers took half a ton of provisions away with them.

It was 29 April 1864, and the episode known as the Chilcotin War or the Bute Inlet Massacre had commenced.

William Brewster and his men had sailed from Victoria aboard the F.P. Green on 16 March. The party was multinational, with men from Lancashire, Derbyshire, ’Scotchmen’, a Bavarian, a French-Canadian, and James Goudie (or Gaudet) described as ‘a half-breed’.

James Goudie was twelve when he arrived in Victoria with his sister Sarah and her husband, George McKenzie, in 1849. At the time, Victoria was in its infancy and was still known as Fort Victoria.

Goudie was part of William Brewster’s advance party, along with John Clarke, an Englishman, the French-Canadian Baptiste Demarest and a Homathko First Nations man Qwhittie (Tenas George). It was around seven o’clock in the morning of 30 April; Brewster and his men had risen early and had breakfasted. Qwhittie was washing the breakfast dishes when a fusillade of shots rang out; James Goudie was the first of the advance party to be shot; a bullet in the shoulder struck him; the twenty-seven-year-old tried to escape by fleeing down a hill but was hit again, this time in the temple and crumpled to the ground dead.

John Clarke received a bullet to the groin, and a second bullet smashed into his thigh. As Clarke tried to regain his feet, one of the five Tsilhqot’in warriors that had launched the attack cleaved his head open with a hatchet.

Baptiste Demarest ran for his life when he saw Goudie and Clarke struck down. He tried to find sanctuary behind a tree when he saw a pair of Tsilhqot’in warriors advancing towards him; Demarest fled down the hill towards the fast-flowing Homathko River, preferring his chances in the river, he dived in. No sign of Baptiste Demarest was ever found, and it is supposed that he drowned in the surging river.

Brewster was in advance of his comrades blazing the trail. Brewster was shot in the head and was finished off with a blow to the head by a warrior wielding Brewster’s axe.

After seeing Goudie killed and then John Clarke dispatched by the hatchet-wielding Tsilhqot’in warrior and the apparent escape of Demarest, Qwhittie turned on his heels and raced towards the main camp.

Expecting to find safety in the main camp, Qwhittie was soon disabused of his hopes. Instead, what he met was a scene of utter carnage. At daybreak, Edwin Mosely and the two men he was sharing a tent with, James Campbell, ‘a Scotchman.’ and Joseph Fielding, a native of Derbyshire, were asleep when the Tsilhqot’in warriors reached the workers’ camp. ’The savages were armed with muskets, axes and knives and lifted up the end of the tent, whooped and fired immediately—shooting fielding and Campbell.’ The assailants pulled the tent down on top of the men and started to hack and slash at the tent’s inhabitants with their knives and hatchet.

Mosely had managed to shield beneath a tent pole and avoided injury. Campbell and Fielding were not so fortunate and died within moments. The attackers, believing that all inside the tent had been killed, moved on to attack the rest of the road builders.

Mosely crept out from under the fallen tent and ran towards the river, ‘which was only about two steps distant.’ He ran through the shallow water, ‘after running about 100 yards he turned and looked towards the scene of slaughter saw a large number of Indians, squaws and children.’

The Tsilhqot’in were gathered around the tent containing the crew’s provisions. Charles Butler (or Bottle), acting as cook for the company, had been killed inside the tent. Mosely watched from his hiding place concealed by the brush on the river’s far bank. Butler had served on the Boundary Commission, had also been a sapper in the British army, and had latterly worked as a broker in Victoria.

Edwin Moseley continued going downriver, ‘leaping from boulder to boulder on the bank.’ He had journeyed about a mile from the scene of the attack on the road builders’ camp when he saw a ‘man ahead of him crawling along.’ Mosely assumed the man to be ‘one of the murderers; but on approaching he saw that he was one of his company.’

The man was Peter Petersen (Peterson), a Dane and a fellow survivor of the attack on the camp. Petersen had been shot in the left arm and was suffering greatly from his wound. Like Mosely, Petersen had used the river to effect his escape.

The survivors continued to traverse the river for another two miles before the pain grew too much for Petersen, and he crawled into some rocks to hide. Mosely continued with his odyssey; his goal was to get to the ferry and find sanctuary with Timothy Smith.

When Mosely arrived opposite the ferry, he shouted for Smith to carry him across the river; when he received no answer, he crawled into the brush and lay down. A short time later, Mosely was joined by Petersen, who had summoned enough strength and willpower to carry on.

Petersen ‘also hallooed with like ill success.’ The pair decided that Smith was asleep and continued to shout across the river regularly during the rest of the day. They remained on the same side of the river until noon the next day, when Philip Buckley, the last survivor of the dawn attack, joined them.

Buckley had been asleep in his tent when the Tsilhqot’in launched their attack. One of the warriors burst into Buckley’s tent and struck him in the head with the butt of his musket. Buckley leapt to his feet and knocked the man down.

He raced towards the tent door where two other Tsilhqot’in men were placed. They both stabbed him in the side. As he raised his arm to hit one of the men, he received another wound and fell to the earth just outside of the tent.

Ignoring Buckley, the warriors rushed past him into the tent, attacking the other occupant, John Hoffmeyer (or Hoffman). Hoffmeyer was a native of Bavaria and was described in The Victoria Daily Chronicle as an ‘old Puget Sound hunter.’

Buckley revived while the Tsilhqot’in were busily engaged in the murder of the rest of the crew. He crawled into the undergrowth and lay hidden until noon when he struck out towards Charles Brewster’s camp.

Night had fallen by the time the wounded Buckley neared the advance camp. In the distance, he could hear dogs barking and see the glow of fires; Buckley knew that Brewster’s gang had no dogs with them and concluded that they, too, had fallen victim to the Tsilhqot’in warriors.

Buckley concealed himself in rocks until daybreak when he set out towards the ferry. Buckley saw no signs of the Tsilhqot’in and joined Mosely and Petersen opposite the ferry.

The three men crossed the river using a guy rope stretched across the water and fixed a loop into the rope. Buckley got into the loop and slowly, hand over hand, traversed the river until he was a few feet from the far bank. Then, he dropped into the water and swam to the shore. Once he climbed out of the water, the other men followed suit.

The men discovered that the skiff used to ferry men and provisions across the Homathko had been smashed into pieces. The survivors discovered a large pool of blood near the fire where Timothy Smith cooked his meals. Nearby, there were signs of an object having been dragged along the ground towards the river and thrown into the water.

A short time later, the three men were joined at the ferry by two French Canadian packers and ‘five Bute Inlet Indians.’ These men had come from the head of the inlet, having heard of the massacre of the road crew ‘from an Indian who had worked for Brewster’s party, and who had been saved by the Chilicootens’; this man was presumably Qwhittie.

The newcomers repaired the skiff, and Mosely, Petersen and Buckley, along with one of the packers and two Indigenous men, headed downriver to the Half-way House, fifteen miles from the head of the Inlet. They met another First Nations man there, who transported them by a commodious canoe to the town site from where A. Samper penned his letter to Alfred Waddington.

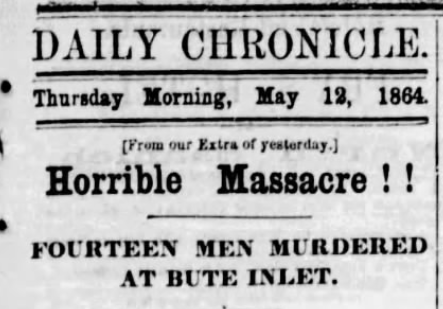

They then travelled in another canoe from Bute Inlet to Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, where they caught the Emily Harris to Victoria, arriving at 8 am on 12 May. Petersen, who reported that the man who had shot him was employed ‘in packing drills from the blacksmith shop’, and Buckley were sent straight to the hospital.

Victoria Daily Chronicle Thursday, 12 May 1864

On 15 May, the gunboat Forward was dispatched to Bute; Alfred Waddington and 28 special constables were onboard. The Forward ascended the Homathko to the scene of the attack on the road builders’ camp. They found signs of the bodies of the slain men having been dragged down to the river bank and thrown into the water. A coat believed to have belonged to Baptiste Demarest was found with two bullet holes in it.

Waddington’s party buried some of the men killed at the camp; it is unclear how many and if they were retrieved from the Homathko. The tents belonging to the crew had been cut into shreds.

The area around the ferry where Timothy Smith had been killed was found strewn with provisions and utensils. Groceries worth about $200 were found hidden in bushes.

The party from the gunboat found the bodies of Brewster, Clarke and Goudie (Gowdy in the Daily Chronicle). The men had been ‘horribly mutilated.’ The Daily Chronicle added, ‘Brewster’s heart had been torn out, and a friendly Indian reports that the murderers chopped it up and ate it!’ The paper also informed its readership that Waddington had in his possession the bullet that killed Smith.

Meanwhile, in the diggings, news of the killings had spread. At Soda Springs, James Ogilvie and Donald McLean were recruiting volunteers among the miners to apprehend the murderers of Brewster and his crew.

Donald Mclean was an interesting character. He was born in 1805 at Tobermory on the Hebridean island of Mull. He joined the HBC in 1833 as an apprentice clerk. After serving at several posts in the western United States, he was transferred to the New Caledonia District in 1842. He spent time at the Babine, Chilcotin and McLeod posts. He also worked at the Fraser River post of Fort Alexandria.

He was appointed chief trader in 1853 and two years later took over at the Thompson’s River Post (Kamloops) when the incumbent Paul Fraser died. A visiting Royal Navy lieutenant described McLean as ‘A finer or more handsome man I think I never saw.’ The local First Nations peoples were not so enamoured with Mclean, nor were his superiors at the HBC; he was summoned to Victoria in 1860 and censured for his high-handed attitude. McLean resigned the following year.

McLean moved his family to the Bonaparte River in the Cariboo region, where he raised livestock and ran ‘McLean’s Restaurant’ catering to travellers.

While Ogilvie and McLean set about raising their ad-hoc militia in the Cariboo District at Victoria, the newly appointed Governor of British Columbia, Frederick Seymour, ‘a man of much ability and energy’, ordered gold commissioner, William Cox, to go overland from the Cariboo with a volunteer force to capture the Tsilhqot’in men responsible for the death of the road crew. At the same time, Chartres Brew, the Chief of Police, was dispatched by ship from New Westminster. Seymour, Brew and Cox, a ‘fat, tall, thick set fellow,’ were all Irish-born.

There was also an American company enrolled. Commanded by Captain William Smith, they numbered 25 men., and proposed to offer their services to Frederick Seymour, ‘reserving the right “to use the Indians up” after a peculiar method of their own. They also stipulate to be subject to the orders of their captain only.’

Commissioner Cox left Alexandria on 8 June with a force of fifty men with a month’s worth of provisions. In a report sent to Governor Seymour, Cox said that his party had ‘discovered, covered in a ditch, the body of William Manning. One side of the head was completely crushed in, and a musket-ball had passed through the body. I held an inquest and had it decently interred.’ William Manning farmed near Puntzi Lake.

The following day, 13 June, Cox dispatched Donald McLean, his son, and two other men to ‘Chilcoaten Forks’ to try and obtain the services ‘of Alexis, an Indian chief.’ Cox described the land as being heavily wooded and covered with brush. If he could be induced to help the settlers, Alexis would be used as a guide and interpreter.

In the early afternoon, a scouting party returned and reported to Cox that they had ‘seen an Indian dog on the ridge of a wooden hill.’ The commissioner sent a cohort of eight men with an ‘Indian boy.’ He ordered them to follow the dog and persuade any Indigenous they met to return to the camp with his men ‘so that I could make my mission known amongst them.’

The men had followed their guide through woods for about half a mile when the guide signalled that Tsilhqot’in were in the area. Before the pursuers could react, the Tsilhqot’in laid down a desultory fire.

The men of the volunteer force immediately returned fire, and the Tsilhqot’in started to retreat through the woods, ‘passing from behind one tree to another, whooping as they flew.’

One of the volunteers received a musket ball in the thigh. Hearing the crescendo of gunfire at the camp, Cox sent out a second group of eight men to support the original party. He and James Ogilvie, with four men, then left in a different direction to surround the Tsilhqot’in.

Finding that their foe had slipped away, Cox and his men returned to their camp, where they constructed breastworks for their protection during the night.

When Donald McLean returned to report to Cox three days later, he had met with Alexis’ family. Although the Indigenous were initially wary of McLean’s party, he assuaged their concerns. Alexis was away from the camp in the mountains, and his family promised to send for him, and ‘we might expect his advent in four or five days.’ The men informed McLean that the killers of Brewster and his crew were at large in the country between Bute Inlet and Puntzi Lake.

Cox finished his report by telling Seymour that if Alexis were a no-show, ‘which is unlikely,’ he would march the 65 miles to recruit ‘Anaham an influential and good Indian, as a guide.’

The Victoria Daily Chronicle reported that Chartres Brew arrived at Bute Inlet with his cohort of men on 19 June. Brew enlisted thirty warriors to act as scouts, and these men left with him.

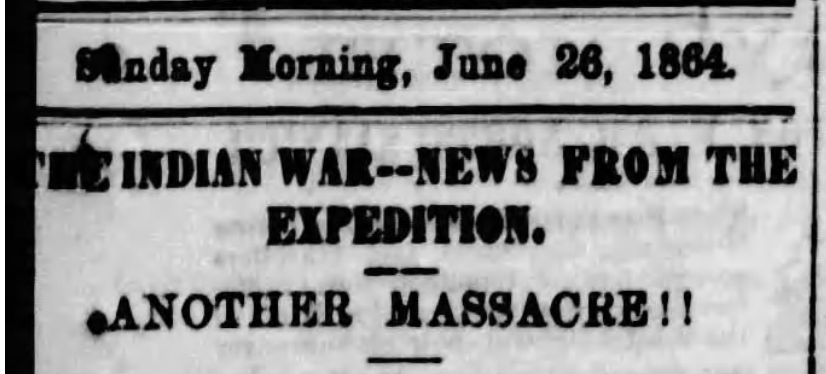

With Governor Seymour onboard, the vessel Sutlej reached Bentinck Arm (Bella Coola) on 18 June. Passing up the Arm, they encountered a canoe carrying two men, Barnett (or Barney) Johnson, ‘badly wounded in the face and knee’, and Malcolm McLeod, a ’Scotchman; wounded in the face and hands with buckshot.’ After being looked after by the naval surgeons, the two wounded men revealed that they had been part of a group of eight led by Alexander McDonald.

Ten days before, travelling along the bank of the Bella Coola River, heading towards ‘Benshee Lake’ with 28 pack animals laden with goods and provisions, they were ambushed by ‘Indians’.

Peter McDougall died at the outset of the fighting, ’shot through the breast with a rifle ball’, and several of his comrades were wounded. The settlers fled into the woods and became separated. Alexander McDonald found cover behind a tree and was last seen ‘firing with a revolver at the savages.’

Johnson and McLeod didn’t tarry to learn the fate of McDonald with any certainty. Instead, they raced towards the Hamilton ranch on the Bella Coola River. Upon reaching the ranch, the two wounded men encouraged Hamilton and his family to embark in a canoe for Bentinck Arm.

The canoe had only just been launched into the waters of the river when ‘several of the redskins appeared on the bank, but too late to overtake the fugitives, who arrived safely on the arm on the same day.’

Three more ambush survivors, George Ferguson, John Grant and Frederick Harrison, reached Bentinck Arm the same day. Harrison was described as slightly wounded; Grant, an American, had received wounds in the arms and thigh, while Ferguson, an Englishman, escaped uninjured. Clifford Higgins, a Lancastrian, was, along with Alexander McDonald, missing and presumed dead.

Victoria Daily Chronicle Sunday, 26 June 1864

Early in July, the death of Donald McLean was being reported in the Victoria newspapers. The Daily Chronicle reported in its Sunday, 3 July issue that rumours had reached Lillooet concerning the former chief trader’s alleged slaying along with two other men by ‘Chilcoaten Indians’; the newspaper reassured its concerned readership that the report was erroneous.

The report of the death of Donald was false, but only by a few days. On the last day of July, it published a letter from L. Fisk, informing the wider world that McLean was indeed dead. Fisk revealed that he had been killed on 17 July, about 180 miles from Alexandria, near the ‘Coast Range’ mountains. He was buried near a small lake that was named in his honour.

Mel Rothenburger, a descendant of McLean’s, wrote in his 1993 book The Wild McLeans that the erstwhile chief trader was scouting with just one companion, a First Nations man known as Jack, when he was shot in the back from ambush.

On hearing the shot and seeing McLean fall, Jack immediately raced back towards where the main body of the men were still encamped. Jack almost collided with Harry Wilmot as he ran back towards the camp.

Mounted on a horse, Wilmot urged his steed along the trail until he came across McLean lying face down. Wilmot leapt from his horse, thinking that McLean might merely be wounded; he rolled the shot man onto his back. Realising that McLean was dead, Wilmot retraced his route to Cox’s camp.

On his way back to the camp, Wilmot encountered Duncan McLean, son of the slain man. Duncan asked Wilmot if he had found his father. Wilmot’s instinct was to avoid the question, but when Duncan insisted, Wilmot admitted that the senior McLean was dead.

According to Rothenburger, Duncan was so grief-stricken by the news that he pulled his revolver from his belt, cocked it, and was in the process of levelling it at his head when Wilmot grabbed the weapon from the young man.

When Commissioner Cox reached Wilmot and the younger McLean, he detailed two men to return with Duncan to the camp. Cox had Donald McLean’s body moved back to the camp when they reached the scene of his slaying.

After the remaining volunteers reached the crest of a hill, a member of the corps named Fitzgerald sighted several Tsilhqot’in, including Klattasine and Anukatlk, the man who had killed McLean.

Cox’s party had been reinforced by more men led by James Ogilvie, and the Commissioner believed that he had the Tsilhqot’in men surrounded. The volunteers opened fire, and a ball struck a tree close to where Klattasine stood.

The Tsilhqot’in escaped by swimming through a lagoon. It is unreported as to whether the First Nations men thumbed their noses at their pursuers when they got out of range of Cox’s men’s firearms.

The volunteers returned to camp, where a funeral service was held for Donald McLean. After the body was interred, the ground was flattened ‘and the surrounding brush burned so that the Indians might not discover the spot and exhume the body.’

Governor Frederick Seymour informed the British Columbia Legislature in March 1865 that Sophia McLean, the widow of the slain Donald McLean, was to receive a pension of £100 for the following five years.

Fifteen years after their father’s death, Allen, Charlie, Archie McLean, and their friend Alex Hare would write their page in the history of British Columbia; these four men will have their story told later.

The day before Donald McLean died, The Victoria Daily Chronicle reported the ‘ARREST OF A SUPPOSED BUTE INLET MURDERER.’ The report stated that a party of five, three white men and two ‘Indians’ had arrived at Nanaimo from Bute Inlet; with them, they had brought a ‘Chillicoaten Indian who is charged with having aided in the massacre of Brewster and party. He will be taken to New Westminster for trial.’

The following day, the paper clarified that no supposed murderer had been arrested; the two First Nations men with the party were Qwhittie (Tenas George) and Squinteye (Inuqa-Jem); the latter was ‘in no way to be trusted, but little George is a truthful lad.’

Squinteye was believed to know more about the murder of Timothy Smith, the ferryman, than he was prepared to say. Squinteye wasn’t suspected of taking part in the murders, but he might have been involved in moving some of the plunder from the site of Smith’s murder. The two men were being taken to Bentinck Arm with the expedition to identify any of the murderers should they be apprehended.

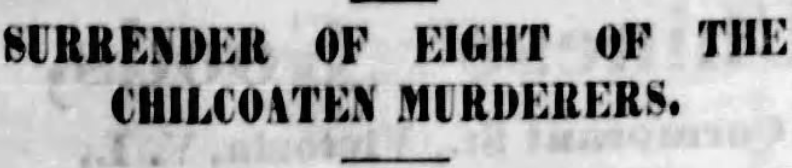

On the morning of 15 August, William Cox’s party was camped at the old Hudson Bay post of Fort Chilcotin on the Chilko River when Klattasine and seven other wanted Tsilhqot’in men walked into the camp.

Cox and Klattasine exchanged messages before the Tsilhqot’in warriors descended on Fort Chilcotin. The Tsilhqot’in misinterpreted a message they had received from the commissioner as guaranteeing their freedom; however, when they reached Cox’s camp, they were immediately arrested and secured. Cox denied giving Klattasine any guarantees and regarded the men coming to the camp as an act of surrender.

Governor Seymour’s secretary furnished the British Columbian with a statement in which ‘Klatsassin’ informed Cox that, ‘I have brought seven murderers, and I am one myself. I return you one horse, one mule, and twenty dollars for the governor, as a token of good faith.’

He named the others of the party as Telloot, another Tsilhqot’in ‘chief’, who joined with Klattasine after the murder of Timothy Smith. The other men were Chee-loot, Tapitt, Piem, Chassis, Cheddiki and Sanstanki.

Victoria Dily Chronicle Thursday, 25 August 1864

Klattasine added that there were ten other men at large, ‘these men I know cannot be caught before the early spring, when they must come to the lake for subsistence.’

Three others were dead: Alexander McDonald had killed one man; the other two men had died by their own hands; Klattasine reported that there were ‘twenty-one Indians implicated in the massacre.’

He also revealed that Anaham’s party took most of the goods that were plundered from the road crew, ‘and are now starving, and eating the stolen horses; and also took all the stolen money from me, as he said he wished to return all to the whites.’

When the prisoners were taken, Cox sent a courier to Fitzgerald, who was coming up with a train of supplies, requesting him to get an additional force of ten men. Fitzgerald immediately returned to Alexandria but was only able to recruit one volunteer.

Fitzgerald arrived at Quesnellemouth on 2 September, sent by Cox to procure shackles for Klattasine and his followers. The prisoners had been confined in a structure built of logs. ‘A guard is maintained both inside and out, night and day, and fearing after leaving his present well fortified position, a possibility of escape, Mr. Cox, with his usual precaution, sent a pair of bracelets for each of them.’

Cox intended to transport his prisoners to Williams Lake or Quesnellemouth ‘with the utmost dispatch where they are to have a fair trial.’

When William Cox received Klattasine and his followers’ surrender, Chartres Brew was hunting for Anaham and his followers, who, according to Telloot, were the chief drivers in the attack on Alexander McDonald and his pack train.

Brew ordered ‘Mr. Elwyn to construct rafts and proceed down…and cross the Memyo River and ascertain whether any Indians were encamped on its south bank.’ Once Elwyn returned, the whole party would decamp to Puntzi Lake and wait for supplies from Fort Alexandria. On the morning of 22 August, Brew’s supplies were running low, so his men butchered a horse and ate it for breakfast.

Brew’s party had been having a hard time; travelling from Tatla Lake to the area around Taco Lake, they found nothing but recently abandoned First Nation villages. Bickering between the men, disobedience of orders, and an air of unhappiness had taken root among the corps of volunteers.

Commissioner William Cox and his party and their Tsilhqot’in prisoners arrived at Fort Alexandria on 9 September. Cox arrived at Soda Creek a few days later and, from there, passed on to Quesnellemouth, where a dinner was given in his honour.

Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie arrived with his entourage at Quesnellemouth on 27 September. According to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Begbie was born on a British ship at the Cape of Good Hope on 9 May 1819. In 1844, he was called to the bar as a Barrister of Lincoln’s Inn, London. On 4 September 1858, Begbie was appointed Judge of the Supreme Court of Civil Justice of British Columbia.

Begbie, fluent in Tsilhqot’in, interviewed Klattasine in his cell at Quesnellemouth. Klattasine informed the judge that he had not expected to be arrested and brought before Begbie, maintaining that the ‘big chief’ W.G. Cox referred to was Governor Seymour rather than Begbie.

Klattasine told Begbie that if he had known he was going to be arrested, confined and put on trial for the murders of the road crew, Manning and members of the McDonald party, then he would not have approached Cox.

Six of the eight First Nations men apprehended by Commissioner Cox appeared before Judge Begbie in four separate trials. Klattasine and Telloot, along with his son Piem (Biyil, Pierre), Chassis (Chaysus) and Tapitt (Tahpit), were the first prisoners to be tried.

William Cox gave evidence in all the trials, recounting his conversations with the accused. Telloot was charged with the attempted murder of Philip Buckley; both Buckley and another eyewitness identified Telloot as the man who had tried to kill him. This same eyewitness placed Klattasine at the scene.

Another witness claimed Klattasine admitted to having killed a settler. Judge Begbie pointed out to the jury that the evidence against Klattasine, Piem, Chassis, and Tapitt was very weak, and they had to be satisfied that ‘all accused were acting in concert.’

The jury subsequently acquitted Chassis, Piem and Tapitt of the charges. Telloot and Klattasine were found guilty. Both Telloot and Klattasine acknowledged ‘that they had assisted in, and many of them executed of several of these murders.’

Tapitt was then tried for the murder of William Manning. The prosecution’s principal witness was an Indigenous woman, the wife of Manning, known as Nancy. Nancy warned that the Tsilhqot’in would ‘come up and kill him after dinner.’ Manning dismissed the warning, believing that he was too well-liked by the Tsilhqot’in.

Manning refused to leave his property; Nancy, the witness, did go; when she looked back, she saw Tapitt shooting Manning and then stabbing him as he lay prone on the ground. Tapitt had disagreed with some of Nancy’s testimony, saying: ‘some words of the woman are true and some are lies.’ When a second Indigenous woman identified the prisoner as one of a group of Tsilhqot’in men near Manning’s property, the prisoner conceded: ‘the words of this woman are right.’

The jurymen convicted Tapitt without leaving the jury box.

Klattasine and Piem were then tried for the murder of Alexander McDonald. The father and son were identified as members of a group who had ambushed the pack train, shooting several of the men, including McDonald. A witness reported seeing Klattasine shoot McDonald, who was then fatally shot by Piem. The jury quickly convicted both men.

Chassis was the last of the prisoners to stand trial. He was accused of killing John Hoffmeyer, the former Puget Sound hunter who had shared a tent with Philip Buckley. An ‘Indian’ bore witness that he had seen Chassis with ‘his face blackened and carrying a musket, approach the camp, and fire shots into the tent.’ Chassis was also judged to be guilty.

Judge Begbie waited until the trials had been terminated before passing judgment. Begbie recorded in his report that he told the men that he had become convinced that each of them had ‘killed, or been engaged in killing, white men.’ He added that he had asked them what their punishment for murder was. ‘Death,’ they answered.

Begbie told them the colonisers’ law was the same. Each of the convicted Tsilhqot’in men then addressed the judge. Telloot said that ‘he was too old to do any harm.’ Klattasine’s answer was similar to that of Telloot. Tapitt stated that another Indigenous man had instructed him to kill a white man. ‘After he had killed him he was sorry and went and sat down.’ He added that it was the first man he had slain. ‘I have never even killed an Indian.’

Begbie passed the death sentence on the five men. Telloot received his sentence for attempted murder the other prisoners for murder. In his report, Begbie described Klattasine as ‘the finest savage I have met.’ He added that he believed Klattasine had ‘fired more shots than any of them.’ Although Begbie took no pleasure in sentencing the five to death, especially taking into consideration how Cox and his party captured the men, he stated, ‘the blood of twenty-one whites calls for retribution. These fellows are cruel, murdering pirates—taking lives and making slaves in the same spirit in which you or I would go out after partridges or rabbit-shooting.’

Peter O’Reilly, the High Sheriff of British Columbia, arrived at Quesnellemouth on Sunday, 23 October, ‘bearing with him the warrant for the executions of the five Chilcoaten Indians, found guilty at the late Assizes held here of participation in the Bute Inlet massacre.’

On Wednesday, October 26th, 1864, at seven a.m., the deputy sheriff and an assistant led the five condemned men a hundred yards from the jail to the scaffold. The Reverend R.C.L. Brown of Lillooet said a short prayer, and then, ‘at a preconcerted signal from the deputy sheriff, the wretched men were launched into eternity.’

A crowd of 250 souls, ‘a large crowd (for such a small place)’, including the High Sheriff, Commissioner Cox, and Stipendiary Magistrate J.B. Griffin, watched with grim satisfaction as ’the culprits all died instantly, and with scarcely a struggle.’

The men were left to hang for thirty minutes, after which their bodies were removed from the gallows and placed in coffins. The men were interred in a piece of land earmarked for a cemetery on the edge of Quesnellemouth.

The Victoria Daily Chronicle reckoned that ‘a more quiet, orderly execution never took place in any part of the world.’

Victoria Daily Chronicle Sunday, 6 November 1864

Cheddiki, who had been captured when he entered Cox’s camp with Klattasine, was sent to New Westminster, where it was hoped sufficient evidence to convict him would be found. Somewhere en route, he slipped away from his escort and escaped.

In an excoriating blog post, Tom Swanky states that notes made by Judge Begbie in the spring of 1862 revealed that settlers in the Puntzi Lake region threatened to introduce smallpox unless the colonisers were granted possession of the land.

The variola first appeared at Puntzi Lake in June 1862. By September, a witness reported seeing 500 graves. Tsilhqot’in tradition states that only two individuals in residence at Puntzi survived the scourge of smallpox.

In 1865, an eyewitness testified that Klattasine executed Alexander Mcdonald and Peter McDougall for their roles in introducing smallpox to the Puntzi Lake region.

Begbie’s notes taken during the interviewing of witnesses during the trials as Quesnellemouth show Manning was warned of the danger he faced on the morning of the day he was killed. He was offered the chance to leave the area or seek sanctuary with the local area leader Alexis, brother of Manning’s wife, Nancy.

Manning believed that the Tsilhqot’in were not serious in their threats. As previously noted, Tapitt was reluctant to murder the settler. The community pointed out that he was the man most aggrieved by the settlers extorting his family’s home. After Tapitt executed Manning, the Tsilhqot’in burned down the Puntzi Lake roadhouse.

On 24 October 2014, Christy Clark, the British Columbia Premier, stood and addressed the Provincial Legislature in Victoria, apologising, ’These…Tsilhqot’in chiefs are fully exonerated for any crime or wrongdoing.’

The Tsilhqot’in chiefs called on the federal government to follow the province’s lead. On 26 March 2018, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau delivered a statement of exoneration in the House of Commons.

The following November, he addressed hundreds of members of the Tsilhqot’in Nation near Chilco Lake, saying, ‘Those are mistakes that our government profoundly regrets and are determined to set right. The treatment of the Tsilhqot’in chiefs represents a betrayal of trust, an injustice that you have carried for more than 150 years.’

Chief Joe Alphonse, tribal chairman of the Tsilhqot’in Nation, said, ‘the apology was significant, not only because it was the first time that a prime minister had visited Tsilhqot’in lands, but because it was made directly to community members.’

© Mark Young 2024

Sources

Books

The Wild Mcleans by Mel Rothenburger

‘…The man For A New Country’ by David R Williams

newspapers

The Victoria Daily Chronicle

The Weekly British Colonist

The Daily Evening Press

The Sacramento Bee

The Marysville Appeal

Websites

https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~goudied/genealogy/james_goudie_jr_1836-1864.html

https://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/old/2.0/smith_h.html

https://www.historylink.org/File/5171

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/tsimshian

https://utppublishing.com/doi/10.3138/cbmh.23.2.541

https://web.uvic.ca/vv/mayors.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klattasine

https://canadianmysteries.ca/sites/klatsassin/home/indexen.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_McLean_(fur_trader)

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio.php?id_nbr=4527

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mclean_donald_9E.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Port_Douglas,_British_Columbia

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tiedemann_hermann_otto_12E.html

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/seymour_frederick_9E.html

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cox_william_george_10E.html

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/begbie_matthew_baillie_12E.html

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barnard_francis_jones_11E.html

https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/waddington_alfred_penderell_10E.html

Leave a comment