By Matthews, James Skitt, Major (1878-1970) – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1612556

Shortly before 4 a.m. on Thursday, 29 April 1915, a watchman working for the Pacific Box Company noticed smoke rising from the Connaught Bridge, spanning False Creek, Vancouver.

The Connaught Bridge, a four-lane, 1,247 metres (4,091 ft) long medium-level steel bridge, was opened to traffic on 24 May 1911. Costing $740,000 to build, it replaced a timber bridge built over False Creek in 1891.

On 20 September 1912, Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, accompanied by his wife, the Prussian-born Duchess Louise Margaret, and their daughter Patricia, visited Vancouver to participate in a renaming ceremony. The bridge was officially known as The Connaught Bridge, but the new name failed to resonate, and most people called it The Cambie Street Bridge. Cambie Street, named for an early city resident, is the street that runs across the bridge.

The Connaught Bridge served the city for seventy years. The current Cambie Street Bridge, constructed between 1983 and 1985 for $52.7 million, opened on 8 December 1985.

Alerted by the watchman, each of the city’s fire halls sent out men and apparatus to fight the fire. A strong wind helped spread the fire north along the bridge’s structure. A lack of fire hydrants on the bridge meant that ‘many hundreds feet of hose had to be laid from hydrants on either end of the bridge.’

The firefighters were having trouble attacking the blaze. With no fireboat, Fire Chief Carlisle ordered men to be lowered by ropes over the bridge. A large hole was cut in the bridge north of the fire, and hoses fed through so those men could attack the fire from underneath.

At around 6 am, ‘Warped and twisted by the great heat’, a section of the bridge described as being around ’90-foot’, collapsed into the water of False Creek. Captain William Plumsteel of no.3 fire hall and C.W Colvin, an engineer with the electricity board, who was trying to cut off the flow of electricity to the bridge, were sent catapulting into False Creek.

Captain Plumsteel and Engineer Colvin were fished out of the water by the crew of the Pacific Dredging Company’s launch Pitt under the command of Captain H. Chinnery. Once returned to shore, Plumsteel declined to go to hospital. Instead, he returned to the bridge ’to warn others of a dangerous place.’

Once the large section of the bridge had plummeted into the creek, the firefighters quickly extinguished the fire; they spent the rest of the morning putting out flames that continued to burn on the bridge.

As firefighters fought to contain the blaze that had broken out on the Connaught Bridge, news arrived that the nearby Granville Street Bridge had also been struck by fire. The Granville fire was not as extensive as the conflagration on the Connaught Bridge. The newspapers reported that the cause was ‘a lighted cigar butt.’

Louis Denison Taylor, the city mayor, had been at the scene of the Connaught Bridge fire since early morning. He was quoted in the evening’s edition of the Vancouver Daily World as saying that the fire proved that the fire department couldn’t afford to lose a single firefighter: ‘If the entire department were here and a fire started in the centre of the city, the whole city would be wiped out.’ He went on to say that fireboats were also a necessity. ‘Fireboats? Why we could have purchased three or four fire boats for what it would cost to repair this bridge.’

On 5 May, J.B Williams, the City Claims Agent, presented a report to the Civic Bridges and Railways Committee stating the fires on both the Connaught and Granville Street bridges were accidental. Williams added that there had been fifty-five fires on the Granville Street bridge. It is unclear if Williams was referring to the second Granville bridge, constructed in 1909 to replace the earlier bridge, which opened in 1889. Assistant Fire Chief Thompson ‘reported on thirty-one bridge fire known to him.’

Williams believed that the fire on the Connaught Bridge was caused by dust in the drainage scuppers, and ‘there were no indications of incendiarism.’ Williams said that if saboteurs had caused the fire, the blaze would have been started on the windward side rather than the lee side.

Alderman Malton proposed that smoking should be prohibited on the bridges because of the belief that a match or cigar was the cause of the blaze, but the committee decided not to enforce the motion.

The committee announced that the tenders working on the bridge would be provided with telephones and have fire extinguishers, which were previously absent from the structure, close at hand.

Despite what Williams told the committee, the Vancouver Sun reported that there had been attempts to sabotage other bridges in the city. On 2 May, there were two arson attempts on the Granville Bridge. Both fires were quickly extinguished; a woman waiting for a streetcar saw three men acting suspiciously before fire broke out. The newspaper noted that ’somebody tampered with the Main Street bridge…is now believed in certain well informed circles. Police…deny they discovered any evidence.’

The same day the fires broke out on the two Vancouver bridges, the Victoria Daily Times was reporting on the arrest of ‘four prominent residents of Vancouver’. The authorities believed that the men were celebrating the advance of the German forces against the Canadian troops near Yypres. The men maintained that they were merely having a housewarming party.

The Daily Times continued: ‘It happened that the first and very heavy casualty list of Vancouver men killed and wounded reached Vancouver on Sunday night…it was an unlucky time for the Germans…to celebrate anything.’

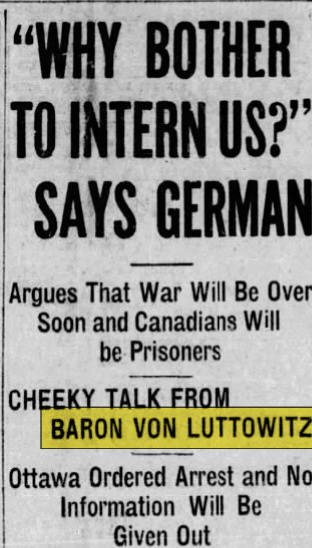

The paper named the men detained as ‘Paul Koop, a capitalist; Baron von Luttowitz, a relative and intimate friend of the Kaiser; Dr. Otto Grunert, and Frederick Stritzel.’ The Daily Times noted that the men would probably be sent to an internment camp for enemy aliens in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island.

The 3 May issue of The Calgary Herald quoted Baron von Luttowitz asking the Point Grey Police Chief Tierney: ‘Why bother about interning us? The war will be over in October. We will be on our way to Germany, while you Canadians will be our prisoners.’

Quizzed by the press, Chief Tierney denied arresting the men for celebrating the German advance on the Western Front ‘but from definite instructions received from Ottawa. The details of which he refused to disclose.’

Instead of being sent to Nanaimo, von Luttowitz, who was on his honeymoon, and his countrymen were sent to an internment camp at Vernon in the Okanagan region of British Columbia. Baroness von Luttowitz and Mrs. Gunnert, Dr. Gunnert’s wife, were interned alongside the men.

As to whether the interned men played any role in the fires that broke out on the two bridges remains uncertain; after their removal from Vancouver to the interior, the record falls silent. It is worth noting that the Vancouver Sun posited whether ‘Fanatic Hindus’ were responsible.

© Mark Young 2024

Sources

The Calgary Herald

The Victoria Daily Times

The Vancouver Daily World

The Province

The Vancouver Sun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1915_Vancouver_bridge_arson_attack

Leave a comment