By Original artist unknown, fl 17th century. Contemporary woodcut, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4986301

On the afternoon of Sunday, 21 October 1638, George Lyde, the Anglican minister of the church of St. Pancras, Widecombe in the Moor, Devon, preached before a congregation of 300 worshipers when: ‘a strange darkenesse,’ fell, ‘increasing more and more, so that the people there assembled could not see to reade in any booke…a mighty thundering was heard…like unto the sound and report of many great cannons.’

The darkness became more pervasive until those assembled inside the church could no longer see their fellow congregants. ‘The extraordinarie’ lightning appeared to enter the building ‘the whole Church was presently filled with fire and smoke, the smell wherof was very loathsome, much like unto the sent of brimstone.’

Witnesses alleged that a ‘great fiery ball’ passed through the church, which caused the worshipers to fall to their knees ’some on their faces, some one upon another…they all giving up themselves for dead, supposing the last judgement day was come, and that they had beene in the very flames of Hell.’

George Lyde escaped unharmed; his wife was not so fortunate ‘the lightening…fired her ruffe and linnen next to her body…to the burning of many parts of her body in a very pitifull manner.’

A woman sitting next to Mrs. Lyde was similarly injured, ‘but the maid and childe sitting at the pew dore had no harme.’ A woman who ran from the church with her clothes on fire ‘had her flesh torne about her back almost to very bones.’ A second woman with similar injuries died that night.

‘Master Hill, a gentleman of good account in the parish,’ was in his usual seat next to the chancel; his head was smashed against the wall of the church; he died later that night, and his son seated next to him received no injury.

Robert Mead, described as a ‘Warriner’ working for Sir Richard Reynolds, suffered a particularly gruesome death ‘his head was cloven,his skull rent into three peeces, and his braines throwne upon the ground whole, and the haire of his head, through the violence of the blow at first give him, did sticke fast unto the pillar or wall of the Church, and in the place a deepe bruise into the wall as if it was shot against with a cannon bullet.’

A man exited the church via the chancel door, a ‘Dogg running out before him, was whirled about…and fell downe, starke dead.’ The man returned to the church and survived, apparently uninjured.

In addition to the four fatalities, around sixty people were injured. The church was also extensively damaged. And a nearby bowling alley was left looking like ‘it had beene plowed’.

At the same time that Widecombe was being assailed, ‘Brixston neare Plymmouth’ witnessed a hailstorm, with the hailstones being described ‘as big as ordinary Turkies eggs; some of them were five, some of six, and others of seven ounces weight.’

Norton, in Somerset, was also beset by a similar storm to the one that struck Widecombe, ‘but as yet wee heare of no persons hurt.’

Also, in London, ‘the lightening was so terrible, fiery and flaming, that they thought their houses at every flash were set on fire.’

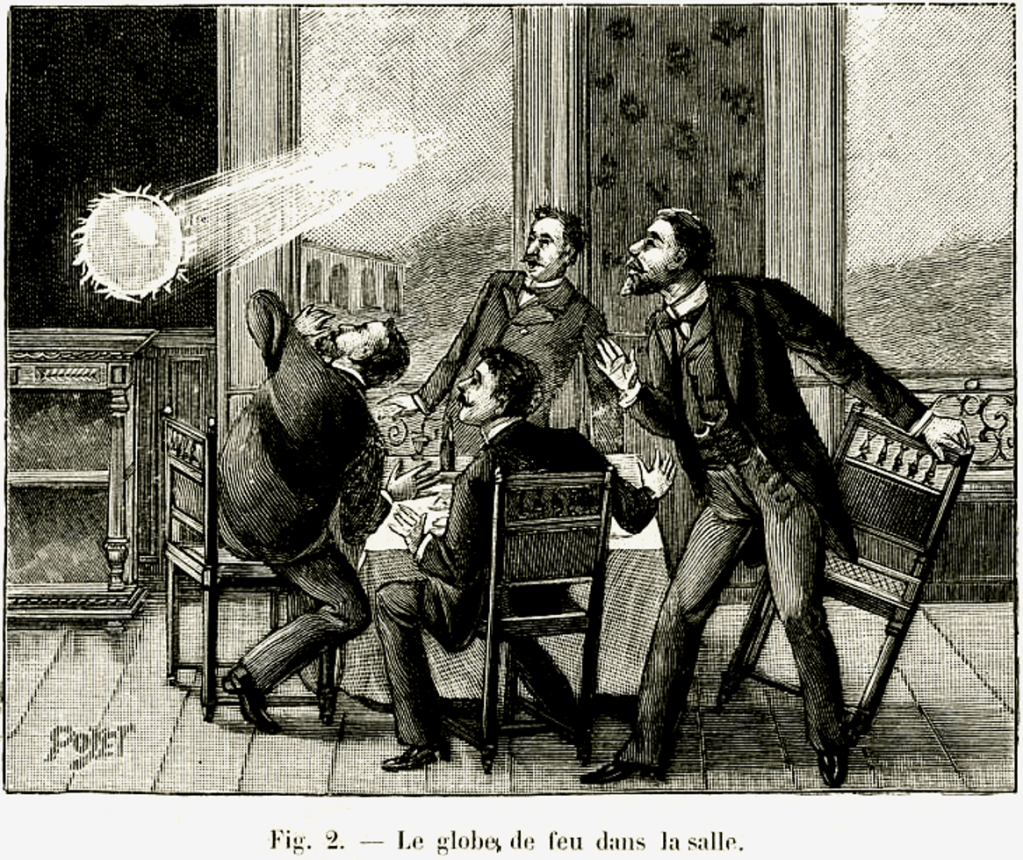

Ball lightning is often theorised to have caused the devastation that struck Widecombe in the Moor. It is an unexplained phenomenon, usually associated with thunderstorms and lasts longer than a lightning bolt. Reports in the 19th century described balls of lightning that, after exploding, left behind a strong sulfur odour. Witnesses in St. Pancras spoke of the strong smell of brimstone as the storm raged. Brimstone is the historic term for sulphur. According to Wikipedia, ‘the lack of reproducible data, the existence of ball lightning as a distinct physical phenomenon remains unproven.’

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58806

If the cause wasn’t ball lightning, perhaps it was the Devil. According to legend, Satan had made a deal with Jan Reynolds, a local card player and gambler, that if the Devil found Reynolds asleep in church, he could have his soul. It is unclear if Jan Reynolds (if he was a real person) was related to Sir Richard Reynolds, whose servant was one of the people killed in St. Pancras

En route to Widecombe, the Devil, having worked up a thirst, stopped at the Tavistock Inn in the nearby village of Poundsgate. The sound of a horse riding up to the inn brought one of the establishment’s patrons to the window.

A tall, dark figure sat astride a coal-black horse, snorting and pawing at the ground. The mounted figure called for a flagon of cider to be brought out of the inn, for he had a devilish thirst.

The landlady took the drink to the stranger, who gave her two coins and then swallowed the cider in one gulp. The rider turned his steed towards Widecombe, and her hands trembling, the landlady returned to the inn’s sanctuary. There, she told her customers that the visitor had been the devil, and she had heard the cider hiss as the stranger swallowed it.

On reaching Widecombe, the Devil secured his horse to the church’s pinnacle; inside, he found the unfortunate Jan Reynolds asleep. Having secured his victim, the Devil threw Reynolds over his saddle, forgetting to untether his horse. As he rode away into the gathering storm, the pinnacle fell through the church’s roof.

At the Tavistock Inn, hooves once more echoed over the silent land. All closeted inside held their breath as the sound grew closer before finally fading into the distance. The two coins the Devil had paid for the cider with had changed to withered leaves.

As he was carried away astride the Devil’s coal-black steed, four playing cards fell from Jan Reynolds’ pocket. Today, if you visit the Warren House Inn near the village of Postbridge, you can see four ancient field enclosures, each shaped like symbols from a pack of cards.

© Mark Young 2024

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Thunderstorm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ball_lightning

Dartmoor.gov.uk

Leave a comment