George Gordon Belt arrived in San Francisco on 7 March 1847, as part of Colonel Jonathan Drake Stevenson’s Seventh Regiment of New York Volunteers after enduring an arduous six-month voyage around Cape Horn.

Stevenson’s force, 770 men strong, was to form part of the American army occupying California. The Mexican-American War had broken out the previous year after a Mexican force of up to 2,000 men had attacked and defeated a United States detachment of seventy to eighty men commanded by Captain Seth Thornton. During the skirmish, the Americans lost 14 men killed, one mortally wounded, six wounded, and the remainder, including Thornton and his second-in-command, captured.

James K. Polk, the 11th President of the United States of America, on learning of the news, went before a joint session of The United States Congress, asking for a Declaration of War, stating:

‘The cup of forbearance had been exhausted even before the recent information from the frontier of the Del Norte [Rio Grande]. Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that …the two nations are now at war.’

The Thornton Affair, also known as the Thornton Skirmish, Thornton’s Defeat and Rancho Carricitos, had occurred in the disputed land North of the Rio Grande and south of the Nueces River. While the Mexicans regarded the Nueces as their northern border, their American contemporaries stated that the Rio Grande was the international border.

Seth Thornton, wounded in the first engagement of the war, was killed in the war’s last action at Churubusco, outside of Mexico City.

In 1845, the United States annexed Texas; Mexico considered this a hostile act, as they still regarded Texas as their territory. The Treaties of Velasco were signed on 14 May 1836 by the Interim President of Texas, David G. Burnet, and the Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna, bringing independence to Texas.

The Mexican Government disavowed the Treaties, as Santa Anna had signed them, while he was held as a prisoner in the aftermath of the Battle of San Jacinto. The Mexican-American war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in the town of the same name on 2 February 1848.

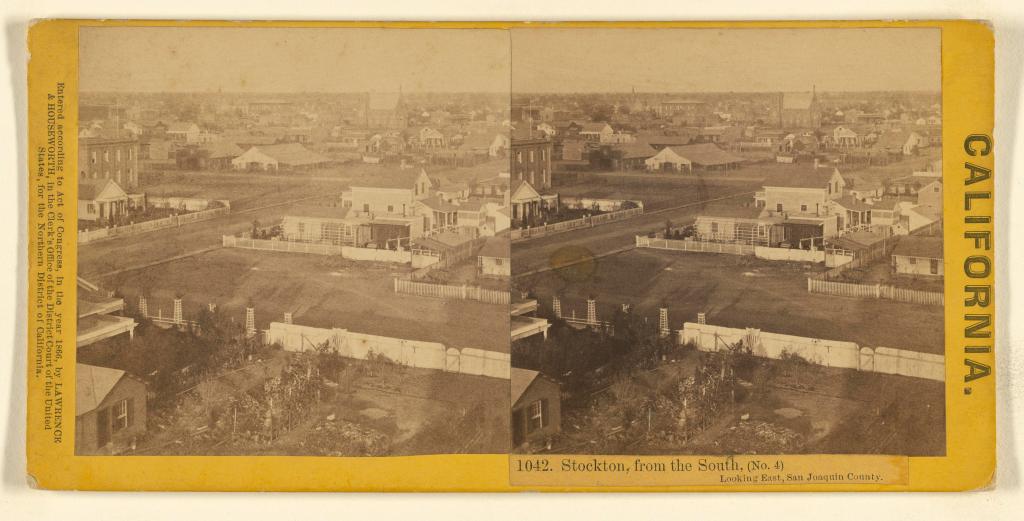

By the time the war ended, George Belt had been discharged from the Seventh Regiment with the rank of quartermaster sergeant and settled in California. Belt married Bebiana Asorca when the war ended; the couple arrived in Stockton in 1849.

In 1850, during the Mariposa or Yosemite Indian War, the federal government appointed Belt as a licensed trader. Belt operated a store out of a tent on the Merced River Indian Reservation. The Mariposa War ran from December 1850 to June 1851 and was sparked by the discovery of gold in the locality. Miners overran the traditional land of the Ahwahnechee.

James D. Savage, a Fresno River trader with the support of Mariposa County Sheriff James Burney, attacked a Chowchilla camp on the Fresno River. Savage’s trading post had been attacked by an indigenous force the previous month.

The Chowchilla, allies of the Ahwahnechees, surprised the militia when they returned fire with pistols and rifles. Savage’s men retreated in disorder; the following day, the memorably named Skeane S. Skeenes, a 2nd lieutenant in ‘Captain’ Burney’s 1st Company, died, the first member of the militia to be killed in action.

The war ended when Tenaya, the Ahwahnechee chief, was captured, and his band surrendered. The California natives were forced from their homelands in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains and onto reservations. It is unknown how many lives were lost during the Mariposa War, but from 1846 to 1873, academics have estimated that between 9,492 and 16,094 natives were killed, with hundreds of others starved or worked to death.

In the years following the Mariposa War, George Belt was to become Stockton’s first Alcalde or municipal magistrate. In October 1856, while still serving as Alcalde, Belt commanded a posse which hanged the outlaw Thomas Hodges, better known by his alias of Tom Bell.

In 1855, Tom Bell was serving a five-year sentence for stealing eleven mules at Angel Island prison in San Francisco Bay. Shortly after being incarcerated, he met Bill Gristy, a notorious thief and arsonist, and the two men soon set about hatching an escape plan. Bell had worked as a doctor in the years before he turned to crime; putting his medical knowledge to use, he faked a severe illness that fooled the Angel Island doctor and enabled Bell and Bill Gristy to abscond.

After escaping, Bell and Gristy recruited five other men and ran a short and bloody campaign. Sometime in 1856, just outside of Nevada City, California, the Bell Gang assailed a teamster who had just delivered beer to an establishment and was leaving town with three hundred dollars in his wallet. A gunfight ensued, and the teamster was shot down, and the outlaws escaped with his money.

On 11 August of the same year, the Bell Gang embarked on the act for which they became notorious—informed by a spy that the Comptonville-Marysville stage contained a large amount of gold. The gang concealed themselves along Dry Creek, just outside of Marysville. When the stagecoach approached, the outlaws rushed it with guns blazing.

As John Gear, the driver, put his team into a gallop, the guard, a man named Dobson, and passengers laid down a withering fire that left one of the would-be robbers unhorsed and dead and wounded others. Three or four passengers on the stage were hurt, and Mrs. Tilghman, the wife of a popular Marysville Barber, was killed.

The calls for the apprehension of the Bell Gang reached a crescendo after the death of Mrs. Tilghman. In September, Sheriff Henson of Placer County discovered Tom Bell and two confederates, Ned Conner and a man known only as Tex, at the Franklin House near Auburn. When the outlaws exited Franklin House, a gunfight broke out; Ned Conner was killed as Bell and Tex shot their way to freedom.

In October, Judge George Gordon Belt, leading his posse, cornered Tom Bell at Firebaugh’s Ferry on the San Joaquin River. Bill Gristy had been captured by authorities a short time before and had revealed Bell’s location when threatened with lynching. Gristy and four of his confederates had a narrow escape a few weeks earlier when a pair of Sacramento detectives named Harrison and Anderson discovered them sheltering in a tent near the Mountaineer House. When night fell, the detectives, with help from two other men, assaulted the fugitives’ tent; Gristy burst through the side of the tent, receiving a scalp wound as he reached his horse. A blast from Harrison’s shotgun killed a man named Walker, two of the outlaws surrendered, and the remaining robber, Pete Ansara, was shot in the leg.

The Stockton sheriff who had apprehended Bill Gristy raced to catch up with Tom Bell; by the time the sheriff reached Firebaugh’s Ferry, Judge Belt and his posse men had jerked the outlaw into oblivion. Before Bell was lynched, he was given time to write letters to his mother and his mistress, Elizabeth Hood. Tom Bell was hanged at 5:00 pm on 4 October 1856.

The same year Tom Bell was lynched, Tom McCauley was sentenced to a term in San Quentin Prison. He and his brother were accused of numerous robberies in the gold camps, and the siblings killed a man in Sonora, Tuolumne County. While Tom was left to cool his heels behind the high walls of the prison, his brother was hanged. Writing years after the event, the Martinez Gazette-News stated that:

‘When (McCauley was) being conveyed to the state prison in the stage from Sonora, his language was so horrible and obscene in the presence of lady passengers that the sheriff found it necessary to gag him.’

Instead of mending his ways when he was released from prison, McCauley instead resumed his life of crime; he rode with a gang of outlaws that haunted the country along the Fresno River. When vigilantes caught up with several members of the outlaw cohort, they strung them up from the nearest trees.

If, after two narrow escapes from the noose, Tom McCauley considered giving up the outlaw life and going straight, he decided against it. McCauley only changed his name, adopting the ‘Jim Henry’ alias.

John Mason, the man who was to ride into infamy alongside Jim Henry, was a southern-born former stableman who was reputed to have killed several men in his dim past. It would seem that he would be the perfect foil for Jim Henry.

The American Civil War erupted on 12 April 1861 when Confederate forces bombarded the Union-held Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbour, South Carolina. The rebels threw 4,000 shells at the Fort; the Union commander, Major Robert Anderson, surrendered to the Confederates the next day.

George Gordon Belt was born in Maryland, a slaveholding state at the outbreak of the Civil War. Support for secession was strong in Maryland, especially in the southern part of the state. Despite this, Maryland never joined the Confederacy.

Thomas Hicks, the governor when hostilities broke out, was pro-slavery but was against secession. Hicks wanted Maryland to adopt a position of neutrality, telling the General Assembly of Maryland on 25 April 1861 that:

‘The only safety of Maryland lies in preserving a neutral position between our brethren of the North and of the South.’

Governor Hicks was persuaded by prominent citizens to call a special session of the General Assembly for the mixed reasons of protesting the North’s attitude towards the South and to oppose secession.

The General Assembly was usually held in Annapolis, but in April 1861, that city was occupied by Union soldiers. Hicks changed the location of the General Assembly to the town of Frederick, now known as the ‘City of Clustered Spires’. Frederick had a pro-Union citizenship.

Once convened, the Assembly decided it did not have the power to commit the state to secession. On 29 April, the Assembly voted 53-13 against calling a state convention which would have had that power.

If Maryland wasn’t for secession, George Belt was. By 1864, the course of the war had changed. After the tide of victories early in the war by the Confederacy, the North had won the battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, an event considered the turning point in the conflict.

Belt owned a ranch on the Merced River, not far from where his posse hanged the highwayman, Tom Bell. From the ranch, Belt organised a group of partisan rangers, whose Raison d’être was to pillage the property of union supporters in the area.

The two most prominent of the rangers were John Mason and Jim Henry. It is unrecorded whether Belt regretted recruiting the two men into his force once news of the duo’s depredations reached his ears. Another man reportedly conscripted by Belt was a native of Virginia, the same state from which Henry is supposed to have originated, and, like Henry, he also adopted an assumed name.

Peter Worthington was the scion of a respectable Virginian family; in either 1839 or 1840, he fled that state after killing a man. He asserted that he had, like Belt, served in the Mexican-American War under the command of Colonel Alexander Doniphan. In January 1847, he killed another man and was imprisoned, breaking out from his jail and heading north-west.

Now Worthington gave up his birth name and became Jack Gordon. He reached an Apache rancheria, possibly they were Chiricahua Apache. Gordon stayed with the Apache for some time, joining with them on raids into Mexico.

After one raid, the Apache were trailed for 80 miles by a troop of the 1st Dragoons, commanded by Captain Enoch Steen. On August 16, 1849, near the Santa Rita copper mines, Gordon shot and seriously wounded Captain Steen.

Gordon was involved in several more adventures. He moved west to California, where in San Jose, he was arrested for horse stealing and was sentenced to two years in prison; he promptly broke free and spent an evening with the famous former Texas Ranger Jack Hays, then acting as sheriff of San Francisco County.

He staked a claim near Coarse Gold Gulch in Madera County. His next exploit was to join Harry Love and his band of rangers as they hunted the notorious Californio bandit and folk hero Joaquin Murrieta.

He returned to California after a brief sojourn to Texas, where he wrestled with a grizzly bear and embarked on more nefarious acts before enlisting with Belt’s Rangers.

The Mason-Henry gang, as they came to be known, first killings took place on the evening of 8 November 1864. It was the day of the Presidential Election that saw Abraham Lincoln re-elected; John Mason and Jim Henry rode up to a cabin on the San Joaquin River, about eight miles below Fresno, belonging to a ‘Dutchman’ named Charley Anderson. Anderson raised sheep and had little contact with anyone except for an ‘Indian boy’ whom he employed as a shepherd.

When Mason and Henry reached Anderson’s cabin, they called him to the door, informing him they had a letter for him. As Anderson opened the cabin door, the two men shot him dead in front of the Indian, reloaded their weapons, turned their horses away and rode off towards Fresno.

Mason and Henry had planned to kill John Chichester next, but on arriving at his property, they discovered that a group of teamsters had set up camp there. Hence, the outlaws continued for another seven miles until they came up on the cabin of a man named Hawthorne.

Hawthorne was an older man with a reputation for hospitality. He lived alone in a small cabin; a short distance away stood a stable where the Visalia stage changed horses. Carlos Y. Guerra, a Californio and two Americans were sleeping at the stable when the two desperados rode up.

In its 18 February 1865 issue, The Contra Costa Gazette reported that:

‘About midnight the murderers arrived, entered the stable…They stated they were after Lincolnites, they were going to kill the old man, and they were also going to get two at the next ranch, the Elkhorn.’

After disarming Guerra and one of the Americans, the other man was unarmed, the slayers of Anderson made for Hawthorne’s cabin. Hawthorne was sleeping when Mason and Henry entered his home; the three men sheltering in the stable heard the sound of the pistol shot that killed the older man.

Soon, the killers returned to the stable and warned Guerra and his companions to stay quiet and not to try and leave the stable. Their bloodlust not yet sated, John Mason and Jim Henry remounted and rode for another seven miles, reaching a shepherd’s hut just as dawn broke. They ate with the hut’s occupant, exchanging news with the shepherd before they set off for the Elkhorn.

On the morning of the election, Cuthbert Burrell arrived in California from Illinois in 1846 and left the Elkhorn Ranch to cast his vote at Kings River, about eighteen miles away. After voting, Burrell was planning to head to Visalia on business. The second man at the Elkhorn, either Robertson or Robinson, was going on the same journey but was leaving later and making the trip by stagecoach rather than horseback.

Robertson had arranged to return from Visalia the same night in the wagon of a man who ‘was engaged in peddling fish between the San Joaquin and Visalia.’ It was agreed that the fisherman would wait for Robertson at Kings River. However, the hour was late when Robertson arrived at their rendezvous, so they remained at Kings River, planning to return to the Elkhorn the following morning.

Mason and Henry found no men at the Elkhorn when they arrived. Robertson’s wife and four children, the eldest a girl aged seven, the youngest a few months old, greeted them warily. The murderers asked for a drink of water. ‘The lady handed a cup that they might get some at the well.’

On learning that no men were present at the Elkhorn ranch, Mason and Henry quenched their thirsts and started on their way. A dog had accompanied the two outlaws, and as they left, their dog was followed by one from the Elkhorn.

Mason and Henry met with Robertson a quarter of a mile from the ranch, returning to the Elkhorn in the fisherman’s wagon. Robertson was unknown to the two men, but when he spotted his dog following after the killers, he asked the fisherman to stop so that he could take the dog home with him.

As Robertson got down from the wagon and started to make a fuss of the animal, Mason and Henry realised who this stranger was. Mason asked if he was Robertson; the man from the Elkhorn looked up from the dog momentarily and affirmed that he was.

Mason fixed him with a hard stare. ‘Then you are the person who said there is not a virtuous woman in the South.’

Robertson immediately denied having said such a thing and unequivocally told the men it was a lie.

‘For whom did you vote?’ Mason pressed him.

Doubtlessly feeling troubled by this point, Robertson responded, ‘This is a strange place to question a man in this manner.’

The outlaws dismounted from their horses at once and, pulling their weapons, told Robertson to get on his knees. As Henry cocked his gun and pointed it at the fisherman, Mason levelled his revolver and said to Robertson, ‘Look down the muzzle of that gun, and swear a lie.’

On his knees, Robertson begged for the men not to shoot him. Mason, not in the mood for mercy, pulled the trigger of his revolver. The bullet struck Robertson in the arm, and he was knocked to the ground. Cradling his arm, somehow Robertson got to his feet and broke into a run. ‘Stop the d—d scoundrel,’ Mason shouted at Henry.

Henry did as he bade, but his aim was poor, and the bullet missed the stricken rancher. Mrs Robertson was at the well drawing water when she heard her husband scream and the report of Mason’s revolver.

Mrs Robertson, with her three older children, gathered about her, watched as Henry rode up to within a few feet of the stumbling Robertson and fired again; this time, he pitched forward onto the ground dead. The newly widowed Mrs Robertson later described herself as ‘Numb and cold.’ In the aftermath of her husband’s murder.

Mason and Henry hung around, reloaded their weapons and spoke of everyday matters with the fisherman, ‘and looked as though they had performed some laudable act, or achieved a great triumph.’

The two men asked the fisherman if he had paper to use as a wad for a shotgun or whisky. For murder is thirsty work. But the fisherman had no whisky, so the killers’ mood turned from affable to hostile once more. ‘They then warned him, at his peril, to proceed to the house slowly without the corpse, to remain during the day and all night there.’

Mason, ‘this inhuman monster, the fiendish murderer.’ Had become aware of the cries of despair from Robertson’s widow and children. ‘Let us go; there is the woman in tears, woman’s tears unman me.’ He declared.

The killers rode off a short way, left the road and waited for three hours, watching the Elkhorn, hoping for the return of Cuthbert Burrell; fortunately for him, Burrell had yet to leave Visalia.

Mason and Henry had left, and darkness was looming when the widow, with help from the fisherman, was able to retrieve her husband’s body and return it home.

The Sacramento Bee of Wednesday, 23 November 1864, reported that the Fresno County sheriff had offered a $500 reward for both Mason and Henry. ‘This is in addition to the $1,000 offered by the governor.’

The same newspaper had reported the month before that two men believed to be the notorious outlaws were shot by a detachment of soldiers commanded by Captain Munday in the vicinity of Fort Tejon; one of the men was killed and the other seriously wounded, it transpired that the men were ‘Perfectly peaceable residents of Fort Tejon and innocent of any crime.’

December 1864, the month after Mason and Henry embarked on their murder ride, Jack Gordon’s colourful life came to an appropriately violent end. He was suspected in the disappearance of several men in Tulare County. And was widely suspected in the slaying of a German prospector who was robbed of $4,000.

He went into business breeding pigs with a man named Samuel Groupie. The two had a falling out, which culminated in a shootout at Tailholt (present-day White River) on or about 14 December. Groupie received severe gunshot wounds but survived. Jack Gordon was mortally wounded; he lingered for a few hours, long enough to ensure that an Indian girl named Chescott, who lived with him, was provided for. The girl was to live with the Levi Mitchell family and receive Gordon’s estate.

Jack Gordon was buried in the Tailholt Boot Hill Cemetery; Chescott was later interred beside him. The day after the deadly shootout, an autopsy cleared Samuel Groupie of murder.

A detachment of soldiers from Fort Tejon tracked Mason and Henry to Sonoma, ‘traveling over nine hundred miles through a most desolate country.’ Before giving up and returning to Camp Babbitt ‘on account of their horses giving out and their inability to get fresh ones.’

Mason, Henry and their cohort were on a horse-stealing raid on the Merced River in April 1865. They robbed a ‘Jew Store’ and cut the Los Angeles telegraph line, taking some of the wire away with them. The Merced County Sheriff W.L. Coots led a posse to pursue the outlaws. Henry was seen in the vicinity of Firebaugh Ferry, where Judge Belt and his posse hanged the highwayman Tom Bell a decade earlier. The band’s rendezvous was forty-five miles from San Juan, near Panoche, in western Fresno County.

Luck finally ran out for Jim Henry in September 1865 after two narrow escapes from the gallows and myriad brushes with the law, soldiers and vigilantes.

On 14 September, a detachment of soldiers from E Company, 1st Cavalry based at Drum Barracks, Wilmington, Los Angeles, accompanied by a posse led by the San Bernardino Sheriff Benjamin F. Mathews, encountered Henry and his gang members at San Jacinto Canyon.

It wasn’t luck that brought the law to Henry as dawn broke on that September morning. John Rogers, a member of the Mason-Henry gang, was sent to San Bernardino to obtain provisions. Rogers got side-tracked and fell to boasting in the saloons; betrayed, he was captured by Sheriff Mathews.

Rogers was persuaded by Sheriff Mathews, a Mormon, to disclose the whereabouts of the gangs’ hideout. It is interesting to wonder what form the ‘persuasion’ took, a threat of lynching or a cocked pistol perhaps.

Whatever the method, John Rogers led the soldiers and lawmen about twenty-five miles south of San Bernadino along the San Jacinto River to the canyon of the same name. The posse approached the outlaw camp quietly, but Jim Henry, who had reasons to be a light sleeper, became aware of their presence and opened fire.

Henry managed to fire off a few rounds as the posse’s bullets flew around him; one of his bullets struck Sheriff Mathews’ brother in the foot. Wounding the posse man was Jim Henry’s last act of defiance. He was shot down almost immediately, his corpse thrown over the back of a horse and transported to San Bernardino. It was discovered that he had been shot fifty-seven times. Henry was photographed on arriving at the town—in the fashion of the time. His erstwhile comrades were scattered to the four winds, temporarily at least. John Rogers, being the exception, was taken back to San Bernardino for questioning by Sheriff Mathews, who would leave office the following month.

A correspondent of the Wilmington Journal had viewed the dead outlaw’s body after he had been returned to San Bernardino; he described Jim Henry as ‘hight five feet, seven inches; weight, 145 pounds; dark auburn hair…about 28 years old.’

After the death of Henry, John Mason and some of his comrades were sighted heading for Holcomb Valley in the San Bernardino Mountains. Holcomb Valley had been the site of the largest gold rush in Southern California, after the man for whom it was named, William F. Holcomb, found gold as he tracked a bear.

It would be another year until justice was served up to John Mason. Mason regularly visited Jack McKenzie’s cabin in the Tejon Canyon northeast of Los Angeles. A woman was believed to be why Mason called frequently at the place. In April 1866, Mason was at McKenzie’s home with a cadre of his men.

McKenzie sent word to men in the settlements towards Los Angeles that the leader ‘of the distinguished firm of Mason &Henry’ was at Tejon Canyon. Six men left the settlements with the avowed aim of capturing or killing the outlaw.

Once the men reached Tejon Canyon, they approached the cabin cautiously, wary of Mason’s reputation. They gained entry to McKenzie’s place and found Mason lying in bed; whether he was alone or if the woman he was visiting was in bed with him is not stated in the sources.

Benjamin Mayfield, a resident of Tulare County, exchanged shots with ‘the wretched man.’ Mayfield walked out of McKenzie’s property unscathed as John Mason’s body lay dead in the blood-soaked bed.

Mayfield’s comrades rounded up the rest of the lawbreakers and took them off to Los Angeles. There were four men taken prisoner—the only one whose full name has come down to us is Tom Hawkins; the others were Overton, O’Brien and Johnson. Overton was a new recruit. Or that is how the media reported it in the immediate aftermath of John Mason’s death.

In May, Benjamin Mayfield, along with J. Overton, presumably the member of the Mason-Henry gang apprehended at Tejon Canyon, was indicted for the murder of John Mason.

Mayfield was tried in Los Angeles in June. The prosecution argued that Mayfield was a member of the outlaw gang rather than a law-abiding citizen, as was reported in the press when news broke of the Mason shooting. Apparently, the charge of murder was dropped against ‘J. Overton’, as he is not mentioned in any of the newspaper reports of the trial.

Mayfield testified that Mason had wanted him to join the gang, promising to shoot him if he refused; as Mason was in the act of drawing his gun, Mayfield shot the outlaw. Mayfield and Overton then buried Mason near McKenzie’s cabin, fearful that the rest of the gang should discover their leader had been killed.

The jury, of whom half were Californios, found Mayfield guilty. Judge de la Guerra sentenced Mayfield to be hanged for the Murder of John Mason on 7 August. The defence immediately moved that a new trial should be held and the verdict set aside. The motion was thrown out. The case was taken to the Supreme Court, which respited the judgement of execution on questions of law.

The response from the press outside of Los Angeles was swift and without exception, condemning the verdict the jury had arrived at. A San Francisco paper said: ‘It would be a lasting shame and disgrace to the State if such a man should be executed for killing so blood-thirsty a miscreant as Mason was.’

The Sacramento Bee agreed, adding: ‘The authorities of Los Angeles are making themselves the accomplices of Mason and Henry…A model set, truly!’

The Chico Weekly Chronicle-Record reckoned, ‘ Instead of being hung, he should receive a reward of at least $5,000.’

On 2 October, the Supreme Court in Sacramento listened to the case put forward by Mayfield’s Defence Counsel, Cadwalader, arguing against the state’s Attorney General, and granted a new trial.

Mayfield supporters wanted a change of venue for the retrial, but the Supreme Court declined their request, and in January 1867, for a second time, he went on trial in Los Angeles. This time, Mayfield had a more sympathetic jury, and after deliberating for fifteen minutes, they acquitted him of the charge.

On Saturday, 14 October 1865, George Gordon Belt received a visitor at his ranch near the mouth of the Merced River. The man calling on Belt was a Mexican named Hidalgo; whether the two men were previously acquainted is unknown. An argument broke out between the two men in which Hidalgo ‘was very lavish in his abuse of the judge and the American population generally.’

Belt ordered his unwelcome visitor to leave, and when Hidalgo refused to do so, the two men drew guns and exchanged shots. Neither man was wounded, and Hidalgo left; doubtless, his opinion of Americans remained the same.

Later the same day, George Belt was riding along the Merced bank a mile from his ranch house when he came across Hidalgo and a Mexican boy named Francisco; the boy may have been Hidalgo’s son. The two Mexicans were busy skinning a beef which belonged to one of Belt’s neighbours, William McFarlane.

Once more gunplay erupted between the two adversaries, Hidalgo drew his pistol, fired and missed. Belt, in return, blasted the supposed cattle rustler with a round from his shotgun; the charge struck Hidalgo in the face and head.

Being shot in the head did no severe damage to Hidalgo; he and Francisco were taken into custody by the sheriff, while Belt, having surrendered himself to Justice Ward, was questioned and released.

George Belt’s life came to an end in an appropriately violent fashion just after noon on Thursday, 3rd June 1868. Belt was walking on the sidewalk outside of the J. A. Jackson and Company’s grain warehouse. He was accompanied by Jackson and a Mr. McFarland, who may have been William McFarlane, the man from whom Hidalgo was accused of stealing the slaughtered beef.

Levi Carter was walking past the warehouse, deep in conversation with W.L. Overheiser, heading towards Main Street, when he saw William Dennis ‘on the sidewalk near some sacks.’

Dennis produced a gun and ‘pointed it at Mr. Belt and fired it.’ George Belt pitched forward onto his face; his right hand was in his pocket, his left across his back. Witness Carter added that ‘I think at the time he fired, he said “damn you!”

According to the testimony of witnesses on Centre Street that afternoon, Belt was unaware of the presence of Dennis, who was behind and a little to the side of him. Overheiser asked Dennis as the smoke cleared: ‘For God’s sake, Dennis, what are you doing?’

Dennis started to walk away with Mr. Nye, an acquaintance; he responded with, ‘What do you mean?’

William Woods was in Mr. Dell’s furniture store when the shooting took place. He stepped onto the street and saw Belt lying on the ground. He saw Dennis standing near to the body; a pistol clutched in his left hand; he asked who had shot Belt. Dennis struck his breast with his hand and answered: ‘I have given him what I promised him.’ A moment later, he added, ‘I will go and give myself up.’

James A. Jackson, the owner of the warehouse and one of Belt’s companions when he was shot, told the coroner’s inquest held the following day that he had been informed that Dennis had made threats against George Belt. Belt did not seem unduly worried by the news, adding that he always carried a Derringer in his pocket.

Jackson told the inquest that he was in his office with Belt and McFarland. Mr Barney joined them and told the three men that ‘there was a good lunch over at Smithson’s.’ Jackson suggested the three visit the restaurant for lunch and were heading there when Dennis spoiled their plans.

Chief of Police W.F. Fletcher found a crowd assembled outside Jackson’s property. Mr. Barney told him, ‘Old man Dennis had shot a man.’

Fletcher found Dennis still in the company of Nye, who told the policeman that Dennis would surrender himself to the authorities. Fletcher detained the assassin and took him to see Judge Brush. He then took Dennis home and received the killer’s pistol; while also at the house, William Dennis furnished Fletcher with a letter he had written to Belt; it stated ‘that Belt owed him… about $5,227,76 and gave Judge Belt notice to pay by the first of April.’ The letter, which Chief of Police Fletcher revealed to the coroner’s inquest, added: ‘the names of several persons that Belt had cheated out of their wages or money.’

Dennis also reported that Belt had made threats against him and that it was ‘it was merely a question or circumstance of time’ as to which of the antagonists would kill the other.

Dr Hudson, the physician who had examined Judge Belt’s prone body on Centre Street, told the inquest that: ‘A pistol ball penetrated the neck, near the lobe of the left ear, severing the carotid artery…also severing the spinal cord, at or near the base of the skull.’

Dr Hudson was the last witness to provide the inquest with testimony. All that remained was for the coroner’s jury to render their verdict: ‘We, the jurors summoned to inquire into the cause of the death of George G. Belt, do find that he came to his death…on Centre Street in the city of Stockton…we further find William Dennis…having shot G.G Belt with a pistol.’

Judge Belt’s funeral was scheduled to take place on Saturday, 5 June, two days after his slaying. His wife Bebiana arrived in Stockton from their ranch on the Merced River the day before with six of the couple’s children. For reasons lost to time, the funeral was postponed and took place the following day.

On Thursday, 28 October, the Sacramento Bee informed its readership that a jury had been selected ‘to try the case of the People vs. Wm Dennis accused of the murder of Judge Belt.’

The same paper reported on page two of its 19 November edition ‘Sentenced.—WM. Dennis, who killed Judge Belt, at Stockton, has been sentenced to State Prison for ten years.’

So closed the final chapter of the story of Judge George Gordon Belt and the Mason-Henry Gang.

©Mark Young 2023

Sources

Books

O’Neal, Bill; The Pimlico Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters

Thrapp, Dan; Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography

Newspapers

San Andreas Independent

The Nevada Journal

The Nevada Democrat

The Placer Herald

Enterprise-Record

Los Angeles Daily News

Mariposa Democrat

Chico-Weekly Chronicle Record

Amador Ledger

Martinez News-Gazette

The Sacramento Bee

Wilmington Journal

Daily Evening Herald

The Shasta Courier

Other sources

Wikipedia

Thoughts From afar Blog

Leave a comment