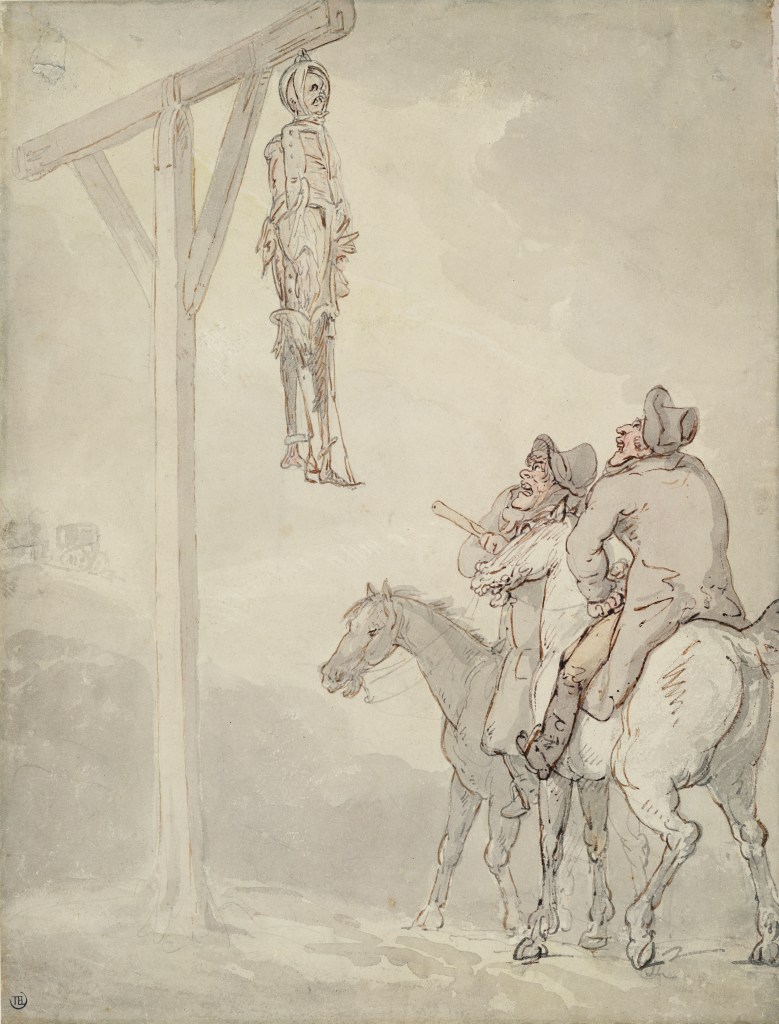

The crowds thronging Kennington Common on a Monday early in August 1795 had gathered to watch as Jerry Abershawe swung from the gallows and into history as the last highwayman gibbeted in England.

Louis (or Lewis) Jeremiah Abershawe was born at Kingston upon Thames in 1772 or 1773. His father worked as a dyer at Bankside, in the borough of Southwark, south of the river Thames. Jerry worked alongside his father for a while before he found employment as a post-chaise driver.

It is uncertain how long Jerry Abershawe lasted as a post-chaise driver; however, it appears that honest work was not to Jerry’s liking. He started his life of crime early; by the age of seventeen, he led a gang of robbers. Abershawe and his associates frequented public houses such as the Bald-Faced Stag tavern at Putney Vale and the Green Man pub at the top of Putney Hill.

Few details of the ‘numerous and daring acts of highway-robbery… as made him the dread and terror of the metropolis and its vicinity‘ committed by Abershawe and his cohorts remain today.

The case that Abershawe is best remembered for, which led to his execution at Kennington Common, occurred on January 13th, 1795. David Price and Barnaby Windsor, two Bow Street Runner constables belonging to the Public Office at Union Hall, Southwark, received information that Abershawe could be found ‘smoking and drinking‘ at the Three Brewers public house in Southwark. The Three Brewers was well known to the constables as the pub was ‘notorious as the resort of thieves and vagabonds‘.

The capture of Jerry Abershawe would doubtless be a feather in the cap of Price and Windsor; the criminal was described in the Newgate Calendar as ‘one of the most fierce, depraved and infamous of the human race.’

The law had caught up with Abershawe before; in 1792, he was tried at Chelmsford for wounding Mr Phillips, a brewer. Abershawe was acquitted, but an accomplice named Stunnell was not so fortunate; he was tried, found guilty, and executed.

It is unknown whether colleagues accompanied constables Price and Windsor as they entered the tavern determined to apprehend Jerry Abershawe. Ale was spilt, and tankards crashed to the inn floor as patrons of the establishment dived for cover. Abershawe had armed himself with twin pistols, and as the constables approached, he positioned himself at the entrance to the parlour, ‘vowing the instant death to any one who should attempt to take him‘.

The thief-takers and highwayman fired their weapons simultaneously, the constables’ shots failing to find their mark. Abershawe having ‘discharged both the weapons at the same moment‘. Barnaby Windsor was sent reeling, shot in the head, while David Price took a ball in the body and ‘languished a few hours in great agony and then died’. The highwayman had previously boasted that ‘he would murder the first who attempted to deliver him into the hands of justice‘. With the slaying of Constable David Price, he had proved as good as his word.

Abershawe, having fired both of his weapons and having no time to reload them, was soon overpowered in the ensuing melee. His wrists bound, he was bundled away into the custody of the Runners.

Abershawe was incarcerated in the foreboding Newgate Prison. The trial was to take place in six months, long enough in the future for Constable Windsor to recover from his head wound, and, the authorities hoped, his evidence would send Jerry Abershawe to the gallows.

The trial of Jerry Abershawe took place at Croydon on July 30th. The presiding judge was Mr. Baron Perryn. Perryn had been made a King’s Counsel (KC) in 1770; six years later, the government appointed him as Baron of the Exchequer in succession to Sir John Burland. Thus far, the most notable trial he had presided over was the Priestley Riots at Warwick Assizes in August 1791.

As he was transported to the court across Kennington Common, past the place where executions took place, Abershawe stuck his head out of the coach’s window and asked the officers escorting him whether they ‘did not think that he would be twisted on that pretty spot by the next Saturday?‘

Abershawe was charged with two indictments. The first, for having ‘at the Three Brewers public-house, Southwark, feloniously shot at and murdered D. Price‘. The second indictment read: ‘for having, at the same time and place, fired a pistol at Bernard Turner (Barnaby Windsor)…with an attempt to murder him’.

The leading counsel for the prosecution was William Garrow, KC. Garrow had been called to the bar in 1783, receiving great renown as a criminal defence counsel. In 1793, the government of William Pitt the Younger appointed him a King’s Counsel, with a brief to prosecute treason and felonies.

In later years, William Garrow would be elected as Member of Parliament for the rotten borough of Gatton; before becoming in 1812 Solicitor General for England and Wales the following year, he was appointed Attorney General for England and Wales. All this lay in the future for William Garrow. That July day in 1795, the only thing that occupied the esteemed Mr. Garrow’s mind was the successful prosecution of Jerry Abershawe.

Garrow believed it had gone well; the jury had taken three minutes to find the accused guilty of Murdering David Price. But then came an objection from the defence concerning a flaw in the indictment—Barron Perryn, unsure of himself, wished to consult the twelve judges of England on the matter. Garrow took umbrage with the judge and insisted that the prisoner be tried on the second indictment, the shooting of Barnaby Windsor. Insisting that it ‘would occupy no great portion of time, as the testimony of a single witness could sufficiently support it’. Perryn quickly approved Garrow’s suggestion, doubtless over the defence Counsel’s objections.

The single witness alluded to by Mr. Garrow was the Bow Street Runner constable wounded in the shootout at the Three Brewers. Barnaby Windsor had recovered enough to attend the court over the spring and summer. The prosecution hoped that he would prove to be a compelling enough witness to condemn the accused.

Those in attendance had expected that Abershawe would act with the same bravado he had displayed on the journey across Kennington Common to the court; thus far, the highwayman had acted with restraint. When he realised there was to be but one witness against him, Abershawe railed against the judge, asking numerous times if he was to be ‘murdered on the evidence of one witness?‘.

How long the jury debated the second charge is unclear. Still, Abershawe harangued the judge until the jury returned with the guilty verdict.

As Judge Perryn donned his black cap before passing sentence on the prisoner, Abershawe placed his hat on his head ‘and pulled up his breeches with a vulgar swagger’. As the judge passed the sentence, Abershawe, the realisation of the sentence dawning on him, ‘stared full in the face of the judge with a malicious sneer and affected contempt.’

Abershawe’s hands and legs were bound, and he was dragged from the court ‘venting curses and insults on the judge and jury for having consigned him to murder.’

When he was in his cell at Newgate Prison, waiting for the day of his execution to arrive. Using the juice of black cherries, Abershawe sketched out various episodes from his criminal career on the white walls of his cell. In one, he is depicted pointing a pistol at the driver of a post-chaise with the words ‘D—n your eyes, stop,’ written with the cherry juice coming from his mouth.

A second scene showed passengers having descended from their chaise being robbed by Abershawe, and a third sketch showed the highwayman firing his pistol into a chaise.

Jerry Abershawe was transported from Newgate Prison to Kennington Common on August 3rd, 1795. Alongside the notorious highwayman were two other condemned souls. The first was John Little, a one-time curator at the Kew Observatory. He was sentenced to be hanged for the murder of James McEvoy and Sarah King in Richmond. He had killed the husband and wife by beating them over the heads with a stone. He was a suspect in the death of a man named Stroud, whose body was found under an iron vice in the observatory. Little was often King George III’s only companion when the monarch visited the observatory. It is presumed that John Little never considered regicide.

The third prisoner set to be executed that day was a woman named Sarah King. She was condemned to hang for the crime of infanticide. A widow was found guilty of killing her newborn ‘male bastard child‘, strangling him with a linen handkerchief, in the parish of Nutfield. Little and King were scheduled to be hanged on the previous Saturday. Their sentences were respited until the 3rd, the following Monday.

In 1725, the Anglo-Dutch Philosopher Bernard Mandeville had a series of letters entitled ‘An Enquiry into the Causes of the Frequent Executions at Tyburn’ published in the British Journal. It is the third such letter describing the morning of an execution that concerns us. Although he is writing a full seventy years before Abershawe and his companions made their last journey, their shared experience is likely to be similar. Mandeville’s observations are worth quoting at length.

‘When the Day of Execution is come, among extraordinary Sinners, and Persons condemned for their Crimes, who have but that Morning to live, one would expect a deep Sense of Sorrow, with all the Signs of a thorough Contrition, and the utmost Concern; that either Silence, or a sober Sadness, should prevail; and that all, who had any Business there, should be grave and serious, and behave themselves, at least, with common Decency, and a Deportment suitable to the Occasion. But the very Reverse is true. The horrid Aspects of Turnkeys and Gaolers, in Discontent and Hurry; the sharp and dreadful Looks of Rogues, that beg in Irons, but would rob you with greater Satisfaction, if they could; the Bellowings of half a dozen Names at a time, that are perpetually made in the Enquiries after one another; the Variety of strong Voices, that are heard, of howling in one Place, scolding and quarrelling in another, and loud Laughter in a third; the substantial Breakfasts that are made in the midst of all this; the Seas of Beer that are swill’d; the never-ceasing Outcries for more; and the bawling Answers of the Tapsters as continual; the Quantity and Varieties of more entoxicating Liquors, that are swallow’d in every Part of Newgate; the Impudence, and unseasonable Jests of those, who administer them; their black Hands, and Nastiness all over; all these, joined together, are astonishing and terrible, without mentioning the Oaths and Imprecations, that from every Corner are echo’d a about, for Trifles; or the little, light, and general Squallor of the Gaol itself, accompany’d with the melancholy Noise of Fetters, differently sounding, according to their Weight: But what is most shocking to a thinking Man, is, the Behaviour of the Condemn’d, whom (for the greatest Part) you’ll find, either drinking madly, or uttering the vilest Ribaldry, and jeering others, that are less impenitent; whilst the Ordinary bustles among them, and, shifting from one to another, distributes Scraps of good Counsel to unattentive Hearers; and near him, the Hangman, impatient to be gone, swears at their Delays; and, as fast as he can, does his Part, in preparing them for their journey.’

Although the prisoners had drunk aplenty before they left Newgate, Mandeville informs us ‘yet the Courage that strong Liquors can give, wears off, and the Way they have to go being considerable, they are in Danger of recovering, and, without repeating the Dose, Sobriety would often overtake them: For this Reason they must drink as they go; and the Cart stops for that Purpose three or four, and sometimes half a dozen Times, or more, before they come to their Journey’s End. These Halts always encrease the Numbers about the Criminals; and more prodigiously, when they are very notorious Rogues. The whole March, with every Incident of it, seems to be contrived on Purpose, to take off and divert the Thoughts of the Condemned from the only Thing that should employ them. Thousands are pressing to mind the Looks of them. Their quondam Companions, more eager than others, break through all Obstacles to take Leave: And here you may see young Villains, that are proud of being so, (if they knew any of the Malefactors,) tear the Cloaths off their Backs, by squeezing and creeping thro’ the Legs of Men and Horses, to shake hands with him; and not to lose, before so much Company, the Reputation there is in having had such a valuable Acquaintance. It is incredible what a Scene of Confusion all this often makes, which yet grows worse near the Gallows; and the violent Efforts of the most sturdy and resolute of the Mob on one Side, and the potent Endeavours of rugged Goalers, and others, to beat them off, on the other; the terrible Blows that are struck, the Heads that are broke, the Pieces of swingeing Sticks, and Blood, that fly about, the Men that are knock’d down and trampled upon, are beyond Imagination, whilst the Dissonance of Voices, and the Variety of Outcries, for different Reasons, that are heard there, together with the Sound of more distant Noises, make such a Discord not to be parallel’d. If we consider, besides all this, the mean Equipages of the Sheriffs Officers, and the scrubby Horses that compose the Cavalcade, the Irregularity of the March, and the Want of Order among all the Attendants, we shall be forced to confess, that these Processions are very void of that decent Solemnity that would be required to make them awful.’

And when the condemned reached Tyburn, or in the case of our subject, Kennington Common, Mandeville goes on to tell us of ‘the most remarkable Scene is a vast Multitude on Foot, intermixed with many Horsemen and Hackney-Coaches, all very dirty, or else cover’d with Dust, that are either abusing one another, or else staring at the Prisoners, among whom there is commonly very little Devotion; and in that, which is practis’d and dispatch’d there, of Course, there is as little good Sense as there is Melody. It is possible that a Man of extraordinary Holiness, by anticipating the Joys of Heaven, might embrace a violent Death in such Raptures, as would dispose him to the singing of Psalms: But to require this Exercise, or expect it promiscuously of every Wretch that comes to be hang’d, is as wild and extravagant as the Performance of it is commonly frightful and impertinent: Besides this, there is always at that Place, such a mixture of Oddnesses and Hurry, that from what passes, the best dispos’d Spectator seldom can pick out any thing that is edifying or moving.’

Abershawe was the most infamous of the three felons set to dance ‘the hempen jig’. Little and King had none of Abershawe’s notoriety. He shared jokes and barbs with the crowd and the officers; undoubtedly, many acquaintances among the public thronged the Common that August day. Perhaps he had friends among those watching on, or perhaps like Bill Longley, who was hanged in 1878, he saw ‘a good many enemies around, and mighty few friends.’ Abershawe kicked his boots off before he was cast off into oblivion.

The Newgate Calendar says he ‘bowed, nodded, and laughed with the most unfeeling indifference‘. And ‘with a flower in his mouth, his waistcoat and shirt were unbuttoned, leaving his bosom open in the true style of vulgar gaiety…venting curses on the officers, he died, as he lived, a ruffian and a brute!’

The hangman presiding over the execution of Jerry Abershawe would have used the short-drop method. Unlike the Long-Drop method, used in the United Kingdom from the 1870s, which broke the spinal column between the 2nd and 5th cervical vertebra, severing the spinal cord and causing death, the Short Drop strangled the unfortunate prisoner. The condemned felon would jerk on the rope’s end like a puppeteer’s marionette; if the prisoner were unpopular, the crowd would undoubtedly enjoy the spectacle—even as he soiled himself.

There are numerous stories of hanged men cut free from the noose, taken away by associates and revived. In 1705, John Smith, a former soldier from Malton in Yorkshire, was found guilty on four indictments and sentenced to hang on Christmas Eve. Smith was strung up for a quarter of an hour; some friends pulled on his legs, hoping to aid with the hanging and end his suffering, while other associates pushed up on his legs to prolong his life. After 15 minutes, a great shout of ‘a reprieve!‘ Rose from the crowd. The authorities had stayed Smith’s death sentence, and the news arrived just in time.

Smith was cut down and taken away to a house near the gallows, where his friends revived him. Some time afterwards, Smith was asked about his feelings during the attempted execution. He replied, ‘My spirits were in a great uproar…I saw a great blaze of glaring light that seemed to go out of my head in a flash. Then the pain went. When I was cut down I got such pins-and-needles pains in my head that I could have hanged the people who set me free.‘ Smith was granted his freedom two months later.

Despite his fortunate escape from the gallows, John Smith did not learn his lesson; twice more, he was tried in cases that could have seen him hanged. He was convicted of housebreaking in the first instance but released on a technicality. When once more he found himself on trial for his life, the prosecutor died the day before the hearing was set to take place, and Smith, again, was set free.

Finally, in 1727, the man familiarly known as ‘Half-Hanged’ Smith was transported to the Virginia Colony aboard the Susannah. Unable to escape trouble, Smith was found alongside another man trying to steal a padlock; his accomplice escaped, but he was apprehended with eight picklock keys. In court, Smith was found guilty of theft. Perhaps he saw a merciful judge; Smith was 66 years old. Or maybe the judge believed that Smith could not be hanged. Whatever the case, with his transportation, Smith was lost to history.

In 1752, the Murder Act came into being. Jerry Abershawe was destined to feel the full force of the new act. A provision of the act stated, ‘that some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy be added to the punishment.’

Jerry Abershawe’s fate was to be hanged in chains’ gibbeted’ to warn others of his ilk. The act added, ‘In no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried.’ The body would either be the subject of public dissection or, as in the case of Abershawe, hung in chains. In July 1828, the government of the Duke of Wellington repealed the Murder Act.

The corpse of the highwayman was hung in chains in an area that came to be known as ‘Jerry’s Hill’, Putney, close to where many of his crimes were carried out.

The August 13th issue of the Bath Chronicle reported, ‘ A wag who went to see it yesterday (Abershawe’s corpse). Wrote using chalk on the gibbet, ‘Part of this tree to be lett.’

Jerry Abershawe was not forgotten in the years after his death. On Friday, January 21st, 1803, the lengthily titled Leicester Journal and Midland Counties General Advertiser reported, ‘ A grand boxing match was appointed between O’Donnell and Hanacau, a Jew, on Wimbledon Common.’ Despite a large crowd, the bout did not occur because ‘the latter of the champions being apprehended and being bound over to keep the peace.’ What remained of Jerry Abershawe still hung in the gibbet because ‘the company for amusement sat down and shared among them Abershaw’s remains, many of them observing he was an old acquaintance. His bones were distributed…Those who obtained his fingers said they would make tobacco stoppers of them.’

In November 1807, a Mr Ireton of Bishopsgate, London, was crossing Wimbledon Common at ten o’clock one Friday night’ near where Abershawe was hung in chains‘ and stopped by a pair of highwaymen. One of the robbers seized Mr Ireton’s bridle while the second man took the small amount of money the merchant carried. Jackson’s Oxford Journal added that ‘they behaved very civilly, regretted he had not more property; wished him goodnight, and then galloped off towards Kingston.’

Another chapter in the story of Jerry Abershawe took place on the Channel Island of Guernsey on Sunday, May 15th, 1808. Robert Wilson, alias James Wood, a private in the Royal York Rangers, broke into the house of Michel Perrin where he encountered 74-years-old Olimphe Mahy, engaged in prayer where ‘he, in the most deliberate manner, cut her throat with a razor, and nearly severed her head from her body.’ The Friday, June 10th edition of the Coventry Herald and Observer article informed the reader that Wilson had been convicted of crimes in England and sentenced to hang. ‘But having obtained His Majesty’s pardon, he was removed from the (prison) hulks into the Royal York Rangers.’

The Gazette de Guernsey had not deemed the murder worthy of mentioning, only reporting on Wilson’s trial and subsequent execution. It noted that ‘the monster, who had committed several other crimes in England…refused all religious exhortations, and finished his days on the scaffold with the sentiments that characterised a real rascal.’

Wilson was hanged on the morning of June 3rd, between 10 and 11 o’clock, at a piece of land at St. Andre, near the bailiff’s Cross Road, known as le Friquet de Gibet, or the King’s Gibbet.

The Coventry Herald and Observer informed the reader that Wilson ‘was concerned with the notorious Abershaw, whom he called his father, and repeatedly expressed his determination to die game, as resolutely as his other associates had done.‘

Wilson was 27 years old when he was executed for the murder of the septuagenarian mother of 10, Olimphe Mahy. Wilson may have been a member of Abershawe’s gang, albeit a junior one. Wilson, like Abershawe, was a Londoner.

It is also possible that Wilson or Wood, the name under which he was hanged, used his alleged association with Jerry Abershawe to add to his notoriety.

Over time, Jerry Abershawe slowly faded from the public consciousness. Robert Louis Stevenson had plans to feature Abershawe in a novel, but nothing came of it. Although he was still mentioned in newspapers in the later decades of the Nineteenth century, today the name Jerry Abershawe has faded, and he is not among the best-remembered highwaymen.

© Mark Young 2023

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerry_Abershawe

https://www.exclassics.com/newgate/ng387.htm

Kennington, 1795: a highwayman’s dance of death on the gallows

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/52240471/lewis-jeremiah-abershaw

https://www.quora.com/How-long-does-it-take-for-a-person-to-die-from-a-short-drop

https://garrowsociety.org/category/the-garrow-society/about-us/

History

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Murder_Act_1751

http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=7302#browse

http://www.britishexecutions.co.uk/execution-content.php?key=7303#browse

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/37650/pg37650-images.html

Newspapers.com

The Bath Chronicle

Leicester Journal and Midland Counties General Advertiser

Jackson’s Oxford Journal

Coventry Herald and Observer

The Gazette de Guernsey

Leave a comment